Bounds on the Capacity of the Additive Inverse

advertisement

2012 IEEE International Symposium on Information Theory Proceedings

Bounds on the Capacity of the Additive Inverse

Gaussian Noise Channel

Hui-Ting Chang and Stefan M. Moser

Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

National Chiao Tung University (NCTU)

Hsinchu, Taiwan

Email: {hui-ting.chang,stefan.moser}@ieee.org

Abstract—A very recent and new model describing communication based on the exchange of chemical molecules in a

drifting liquid medium is investigated and new analytical upper

and lower bounds on the capacity are presented. The bounds

are asymptotically tight, i.e., if the average-delay constraint is

loosened to infinity or if the drift velocity of the liquid medium

tends to infinity, the corresponding asymptotic capacities are

derived precisely.

I. I NTRODUCTION

Recently, Srinivas, Adve, and Eckford [1] presented a new

intriguing channel model describing communication in a fluid

media via emission of molecules. The basic idea is that

in certain situations like, e.g., when nano devices try to

communicate with each other or with some receiving station, it

might not be possible to use traditional signal propagation via

electromagnetic waves because, for example, the nano device

is too small to accommodate the minimal necessary antenna

size or it does not possess enough power.

So the question arises as to how communication could be

established in such a setup. If we assume that the nano device

is inside a certain liquid medium (e.g., blood in a blood

vessel), then one can think of communication based on the

emission of chemical substances. Such a system, of course,

will behave fundamentally different from the usual information

transmission systems. It is therefore a very interesting task to

try to model this communication scenario and analyze it.

The work in [1] is a first attempt to this: there the additive

inverse Gaussian noise (AIGN) channel is introduced. The

model is simplistic and neglects many properties of a real

system, nevertheless, it also shows a Shannon-like beauty

because it simplifies as much as possible without losing the

essentials. It definitely is of fundamental importance with big

impact on practice seeing that nano devices are a very hot

topic in current research worldwide. It also has huge potential

for future research as it allows to slowly incorporate additional

effects that might have influence on a real system.

While we believe that the main and most important contribution of [1] is the description of the AIGN channel, the

authors also present in [1] a first analysis of the channel’s

capacity behavior. In this paper, we build on these results.

We will present new upper and lower bounds on capacity and

establish the exact asymptotic capacity in the cases when either

978-1-4673-2579-0/12/$31.00 ©2012 IEEE

the drift velocity of the fluid or the average-delay constraint

of the transmitter tends to infinity.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. In

Section II we will introduce the channel model and its underlying assumptions more in detail. In Section III we summarize

a couple of mathematical properties and identities related to

the given model, and Section IV reviews the bounds of [1].

In Section V we present our new upper and lower bounds

on capacity, while the exact asymptotic capacity formulas

are given in Section VI. Finally, Section VII outlines the

basic ideas underlying the derivations, and in Section VIII

we discuss the results.

In this paper all logarithms log(·) refer to the natural

logarithm, i.e., all results are stated in nats. For engineering

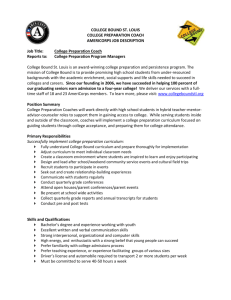

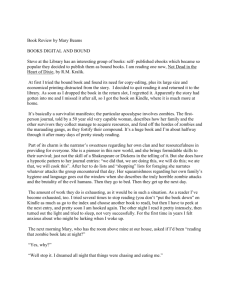

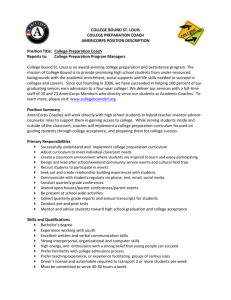

reasons, though, we have scaled the plots given in Figs. 1–4

to be in bits.

II. C HANNEL M ODEL

The basic idea of the system under consideration is that a

transmitter emits a molecule at a certain time into a fluid that

itself is drifting with constant speed. The molecule is then

transported by the fluid and its inherent Brownian motion into

random directions. Once it reaches the receiver, the molecule

is removed from the fluid. To simplify our model, we make

the following assumptions:

• The Brownian motion is described by a Wiener process

with variance σ 2 .

• We only consider a one-dimensional setup where the

position of the molecule is described by a single random

coordinate W . The transmitter is set at coordinate 0 and

the receiver is along the moving direction of the fluid at

a certain distance d. Without loss of generality we will

set d = 1.

• The fluid is moving with constant drift velocity v > 0.

• Once the molecule reaches W = d, it is absorbed and

not released again.

• The transmitter and receiver are perfectly synchronized

and have potentially infinite time to wait for the arrival

of the molecules.

• There are no other molecules from the same type interfering with the communication.

• The channel is memoryless, i.e., the trajectories of individual information carrying molecules are independent.

304

Moreover, in case a molecule overpasses another, the

receiver still can distinguish between them and put them

into correct order.

The basic ideas behind these simplifications are related to

Shannon’s approach when he introduced the additive Gaussian

noise channel [2] and also focused solely on the impact

of the noise, but neglected many other aspects like delay,

synchronization, or interference.

A Wiener process is described by independent Gaussian

position increments, i.e., for any time interval τ , the increment

in position ∆W is Gaussian distributed with mean vτ and

variance σ 2 τ . The increments of nonoverlapping intervals are

assumed to be independent. Here, v denotes the drift velocity

of the fluid and σ 2 is a channel parameter that describes the

strength of the Brownian motion and relates to the viscosity

of the fluid, the temperature, the size and structure of the

molecules, etc.

In our setup of the communication, the positions of transmitter and receiver are fixed, i.e., we need to “invert” the Wiener

process to describe the random time it takes for the molecule

to travel from position 0 to position d = 1. This random time

N has an inverse Gaussian distribution1 that is described by

its probability density function (PDF)

r

λ(n − µ)2

λ

I{n > 0}. (1)

exp −

fN (n) =

2πn3

2µ2 n

Here, I{·} denotes the indicator function that takes on the

values 1 or 0 depending on whether the statement holds or

not. The PDF (1) depends on two parameters: µ denotes the

average traveling time

µ=

1

d

=

v

v

(2)

and λ relates to the Brownian motion parameter σ 2 via

2

d

1

= 2.

(3)

2

σ

σ

Usually we write N ∼ IG(µ, λ).

To transport the information, the transmitter is now assumed

to modulate the emission time X of its molecule (time-position

modulation). After emission, the molecule takes the random

time N to travel to the receiver, i.e., the receiver registers the

arrival time

Y = X + N,

(4)

In addition to the nonnegativity constraint on the input X,

X ≥ 0,

for practicability reasons, the transmitter is also subject to an

average-delay constraint m:

E[X] ≤ m.

C=

1 The

max

fX : E[X]≤m

I(X; Y ).

(8)

Note that the capacity depends strongly on the two most

important channel parameters: the allowed average delay m

and the fluid’s drift velocity v.

III. M ATHEMATICAL P RELIMINARIES

In [1] the authors state the differential entropy of N ∼

IG(µ, λ) using some complicated expression involving derivatives with respect to the order of modified Bessel functions

of the second kind Kν . Luckily, these expressions can be

simplified considerably:

1

2λ

2πeµ3

3 2λ

h(N ) = log

,

(9)

+ e µ Ei −

2

λ

2

µ

where Ei (·) denotes the exponential integral function

Z ∞ −τ

e

Ei (−t) , −

dτ.

τ

t

The general moments of N are given as

r

2λ µλ ν− 1

λ

ν

, ν ∈ R.

e µ 2 Kν− 21

E[N ] =

π

µ

(10)

(11)

In particular, this means that

E[N ] = µ,

µ3

,

E N 2 = µ2 +

λ

µ3

Var(N ) =

,

λ

where X and N are independent, X ⊥

⊥ N . Hence, given some

emission time x ≥ 0, the channel output has a conditional

PDF

=

(7)

Note that other constraints are possible, e.g., it would be quite

reasonable to constrain the maximum delay. We have deferred

the investigation of such assumptions to our future research.

We refer to the model (4) above as additive inverse Gaussian noise (AIGN) channel. It is straightforward to see that

Shannon’s Channel Coding Theorem [2] can be applied to (4)

resulting in a capacity

λ=

fY |X (y|x)

s

(6)

1

E

=

N

1

=

E

N2

1

=

Var

N

1

1

+ ,

(12)

µ λ

1

3

3

+ 2+

, (13)

2

µ

λ

µλ

1

2

(14)

+ 2.

µλ λ

Moreover, we have

λ

λ(y − x − µ)

exp −

3

2π(y − x)

2µ2 (y − x)

2

2λ

2λ

E[log N ] = log µ + e µ Ei −

.

µ

I{y > x}. (5)

name is a bit unfortunate: it is called “inverse” because we have

“inverted” the problem of random position for given time to random time for

given position. However, an inverse Gaussian random variable has nothing to

do with 1/G for G being Gaussian distributed.

(15)

Similarly to Gaussian random variables, inverse Gaussians

are closed under scaling: for any α > 0,

305

N ∼ IG(µ, λ)

=⇒

αN ∼ IG(αµ, αλ).

(16)

However, while the sum of two independent Gaussians is

Gaussian again, this property only holds for inverse Gaussians

with similar parameters: if

λ1

λ2

= 2,

µ21

µ2

(17)

then it holds that for N1 ∼ IG(µ1 , λ1 ) and N2 ∼ IG(µ2 , λ2 )

with N1 ⊥

⊥ N2 ,

p

p 2 .

(18)

λ1 + λ2

N1 + N2 ∼ IG µ1 + µ2 ,

parameter. However, information theorists often consider the

power constraint also as being “part of the channel”, i.e.,

belonging to that part of a system that the system designer

has no control over. So, it is actually not that unorthodox to

plot the capacity as a function of some channel parameter.

The adaptations of the given analytical formulas for these

two cases are straightforward using (2).

6

Finally, it is interesting to note that the inverse Gaussian

distribution is differential-entropy maximizing when the following three constraints are given:

E[N ] = α1 , E N −1 = α2 , E[log N ] = α3 .

(19)

I(X; Y ) [bits]

5

IV. K NOWN B OUNDS ON C APACITY

In [1], two analytical bounds on capacity are presented.

Firstly, an upper bound is derived based on the fact that differential entropy h(Y ) under an average constraint E[Y ] ≤ m+µ

is maximized by an exponential distribution:

h(Y ) ≤ 1 + log(m + µ).

4

3

2

Upper bound (25)

Upper bound (26)

Upper bound (27)

Known upper bound (22)

Lower bound (29)

Known lower bound (24)

1

(20)

0

0

1

2

3

5

6

7

8

9

10

Delay m

This leads to the bound

C = max{h(Y ) − h(N )}

2λ

λe(m + µ)2

3 2λ

1

µ Ei

−

.

−

e

≤ log

2

2πµ3

2

µ

4

(21)

Fig. 1. Bounds on capacity as a function of m. The drift velocity has been

set to v = 2 and the channel parameter λ is assumed to be λ = 41 .

(22)

Secondly, a lower bound is given that is based on (18).

In the definition of capacity the maximization

is dropped and

2

is chosen. Note

instead a suboptimal input X ∼ IG m, λm

µ2

that this choice makes sure that X and N satisfy (17), i.e., we

get Y ∼ IG m + µ, µλ2 (m + µ)2 . This yields

0.5

0.45

0.4

I(X; Y ) [bits]

0.35

C ≥ h(Y ) − h(N )

(23)

m + µ 3 2λ(m+µ)

2λ(m

+

µ)

1

+ e µ2 Ei −

= log

2

µ

2

µ2

2λ

3

2λ

− e µ Ei −

.

(24)

2

µ

0.3

0.25

0.2

0.15

0.1

Both bounds are depicted in Figs. 1 and 2 as a function of the

average-delay constraint m and in Figs. 3 and 4 as a function

of the drift velocity v, respectively.

Upper bound (25)

Upper bound (27)

Known upper bound (22)

Known lower bound (24)

0.05

0

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

0.07

0.08

0.09

0.1

Delay m

V. N EW B OUNDS ON C APACITY

In the following we will present our bounds on capacity.

Similarly to Section IV, we will state the results using only

the channel parameters µ and λ as well as the delay constraint

m.

From an engineering point of view, there are two interesting

scenarios: we can either plot the capacity as a function of

the given average-delay constraint m or as a function of

the given drift velocity v. The former corresponds to the

traditional situation of capacity as a function of the cost,

which usually is power, but here has become delay. The

latter is less traditional as the drift velocity is a channel

Fig. 2. Bounds on capacity as a function of m identical to Fig. 1, but zoomed

in at low values of m.

We start with some upper bounds.

Theorem 1: The capacity of the AIGN channel as defined in

(4) is upper-bounded by either of the following three bounds:

3

λm

1

1

1

+ log 1 + m

;

+

C ≤ log 1 +

2

µ(m + µ)

2

µ λ

(25)

2λ

1

2λ

η−1

C ≤ log λ +

log µ + e µ Ei −

2

2

µ

306

!

λ

2λ −η− 1 µλ

−η

2e K

− (m + µ)

µ

η+ 21

π

µ

1

1

η+2

− log η;

(26)

log 1 + m

+

+

2

µ λ

1

λ 1

1

1

C ≤ log + log 1 + m

+

2

µ 2

µ λ

2λ

1

m

λ

2λ

+ log 1 +

.

(27)

−

− e µ Ei −

µ

2

µ

µ+λ

r

Here, Ei (·) is defined in (10) and Kν (·) represents the orderν modified Bessel function of the second kind. In the second

bound (26), 0 ≤ η ≤ 1 is a parameter that can be optimized

over. A suboptimal, but good choice for η is

(

)

2

η , min

,1 ,

(28)

log 1 + m

λ + log 2 + γ

where γ ≈ 0.577 denotes the Euler number.

These bounds are shown in Figs. 1–4.

5

4.5

4

3.5

I(X; Y ) [bits]

1

+ log

2

3

2.5

2

1.5

1

Upper bound (25)

Upper bound (26)

Upper bound (27)

Known upper bound (22)

Known lower bound (24)

0.5

0

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.45

0.5

Velocity v

Fig. 4. Bounds on capacity as a function of v identical to Fig. 3, but zoomed

in at low values of v.

must be real, i.e., the bound is only valid if

6

2µ2

.

(31)

λ

Note that this lower bound can be simplified considerably, but

for the price of losing its tightness for large values of m or v:

it can be shown that the complicated second last term (second

and third row) can be lower-bounded by − log 1 + 21 :

m

µ

λ

3

λ 3 2λ

2λ

µ

C ≥ log

+

− + kλ + log − e Ei −

λ

m µ

2

µ 2

µ

2π

3 1

.

(32)

− log − log

2 2

e

VI. A SYMPTOTIC C APACITIES

m≥

I(X; Y ) [bits]

5

4

3

2

Upper bound (25)

Upper bound (26)

Upper bound (27)

Known upper bound (22)

Lower bound (29)

Known lower bound (24)

1

0

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Velocity v

Fig. 3. Bounds on capacity as a function of v. The average-delay constraint

has been set to m = 2 and the channel parameter λ is assumed to be λ = 41 .

Next we will state a lower bound.

Theorem 2: The capacity of the AIGN channel as defined

in (4) is lower-bounded by the following bound:

µ

λ

3

λ 3 2λ

m

2λ

µ

+

− + kλ + log − e Ei −

C ≥ log

λ

m µ

2

µ 2

µ

!

r

r

1 λ

λm

2λ

K1

+ k 2 λ2

− log 1 + e µ

m

2 + k 2 λm

m

!!

r

r

1 µλ +kλ

λm

λ

e

K1 2

+ k 2 λ2

+

2m

1 + k 2 λm

m

−

1

2π

log

2

e

The upper bound (22) and the lower bound (29) are asymptotically tight, i.e., when we let v or m tend to infinity, these

two bounds coincide. Hence, we can state the exact asymptotic

capacity.

Theorem 3: The capacity of the AIGN channel as defined

in (4) is asymptotically, when the average-delay constraint

m is loosened to infinity while all other parameters are kept

constant, as follows:

1

3 2λ

λe

2λ

µ

.

− e Ei −

lim C(m) − log m = log

m↑∞

2

2πµ3

2

µ

(33)

In the asymptotic regime when the drift velocity v of the fluid

medium tends to infinity while all other parameters are kept

constant, the capacity is as follows:

3

1

λm2 e

.

(34)

lim C(v) − log v = log

v↑∞

2

2

2π

VII. P ROOF O UTLINES

(29)

A. Upper Bounds

where

k,

r

1

2

−

µ2

mλ

(30)

The upper bounds on capacity are all based on the duality

technique that we have successfully used in our previous work,

307

see, e.g., [3] or [4]. For an arbitrary choice of a distribution

R(·) on the channel output alphabet, we have

C ≤ EQ∗ D fY |X (·|X)R(·) ,

(35)

where D(·k·) is the relative entropy [5] and Q∗ denotes the

(unknown!) capacity-achieving input distribution. To be able

to use this technique, we need to find an elaborate choice of

R(·) that is simple enough to allow the evaluation of (35),

but that at the same time is good enough to result in a close

bound. Moreover, we need to find ways of dealing with the

expectation over the unknown Q∗ .

As discussed in Section IV, the basic idea of the upper

bound (22) was to upper-bound the output entropy by its

maximum possible value, which will be achieved if the output

happens to be exponentially distributed. It therefore does not

come as a surprise that if we choose R(·) to be an exponential

distribution, we can fully rederive (22) from (35).

The upper bound (25) is based on R(·) being an IG

distribution, which explains why for small m it gets close

to the lower (24) (which is based on the IG distribution, too).

The other two upper bounds (26) and (27) stem from

different versions of a derivation based on R(·) being a power

inverse Gaussian distribution [6]: for y > 0,

1+ η2

r

β

α

R(y) =

2πβ 3 y

η2 η2 !2

α

y

β

, (36)

· exp − 2

−

2η β

β

y

where α, β > 0, and η ∈ R \ {0} are free parameters. The

family of power inverse Gaussian distributions contains the IG

distribution as a special case for the choice η = 1.

VIII. D ISCUSSION

We should point out that in [1] the authors have already

concluded from numerical analysis that their upper bound (22)

is very tight. We have now formally proven this by providing

an analytical lower bound that is tight in the asymptotic

regime.

Due to the tightness of the known upper bound (22), it

obviously is very difficult to find improved upper bounds. So,

our focus in the search for upper bounds lay mainly in the lowdelay and in the low-velocity regimes. We tried in particular

to find a bound that would show that the strange behavior of

(22) to increase again as v ↓ 0 is an artifact of the bounding

technique. We were able to find bounds that were strictly better

than (22) and, in particular, we did find bounds that grew more

or less monotonically in v, as we would expect. However, there

is still considerable room for improvement.

Note that the capacity for v = 0 is strictly larger than zero

because even if there is no drift, the molecules still have a

positive probability of arriving due to the Brownian motion.

It is very weird that in this situation of v = 0, the noise that

hurts communication at large speeds becomes the only mean

of communication and is therefore highly beneficial!

In the case when the capacity is analyzed as a function of

the average-delay constraint m, the general picture is better.

While the bound (22) remains strictly bounded away from

zero, we have found an upper bound that tends to zero as

m ↓ 0 (both (25) and (26), but the former is considerably

simpler). Unfortunately, the slope of convergence of our upper

bound (25) and of the lower bound (24) do not coincide. The

exact asymptotic capacity for v = 0 and the capacity growth

rates for v ↓ 0 and m ↓ 0 are projects of our future research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Council

under NSC 100–2628–E–009–003.

B. Lower Bound

The lower bound was inspired by the fact that (22) is

implicitly based on an output that is exponentially distributed.

For large v or m, the impact of the noise N will decrease, i.e.,

it is a good guess that an exponential input might work well.

The lower bound follows from a lengthy derivation based on

1

[7]:

the PDF of Y when in (4) X ∼ Exp m

p

√

1 − my + µλ −kλ

1

fY (y) =

e

Q − kλ

ky − √

·e

m

ky

p

√

1

+ ekλ Q

kλ

ky + √

, (37)

ky

where k is defined in (30) and where this form of the PDF

only is valid if condition (31) is satisfied. Here, Q (·) denotes

the Q-function defined as

Z ∞

t2

1

e− 2 dt.

(38)

Q (α) , √

2π α

R EFERENCES

[1] K. V. Srinivas, R. S. Adve, and A. W. Eckford, “Molecular

communication in fluid media: The additive inverse Gaussian noise

channel,” Dec. 2010, arXiv:1012.0081v2 [cs.IT]. [Online]. Available: htt

p://arxiv.org/abs/1012.0081v2

[2] C. E. Shannon, “A mathematical theory of communication,” Bell System

Techn. J., vol. 27, pp. 379–423 and 623–656, Jul. and Oct. 1948.

[3] A. Lapidoth and S. M. Moser, “Capacity bounds via duality with

applications to multiple-antenna systems on flat fading channels,” IEEE

Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 49, no. 10, pp. 2426–2467, Oct. 2003.

[4] A. Lapidoth, S. M. Moser, and M. A. Wigger, “On the capacity of freespace optical intensity channels,” IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory, vol. 55, no. 10,

pp. 4449–4461, Oct. 2009.

[5] T. M. Cover and J. A. Thomas, Elements of Information Theory, 2nd ed.

New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2006.

[6] T. Kawamura and K. Iwase, “Characterizations of the distributions of

power inverse Gaussian and others based on the entropy maximization

principle,” J. Japan Statist. Soc., vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 95–104, Jan. 2003.

[7] W. Schwarz, “On the convolution of inverse Gaussian and exponential

random variables,” Commun. in Statistics — Theory and Methods, vol. 31,

no. 12, pp. 2113–2121, 2002.

308