“We All Have

Something

That Has

to Do with

Tens”:

Counting School Days, Decomposing

Number, and Determining Place Value

I

t is the seventieth day of school. As in many

other second grades, the children in this class

keep track of how many days they have been in

school. In the following vignette, the children share

number sentences that equal seventy. The second

graders and Mrs. K., their teacher, are gathered on

the rug in front of the whiteboard. Each child holds

a small blue mathematics journal, in which they

record their work. Keaton begins sharing expressions that equal seventy. As he dictates, Mrs. K.

writes “139 – 39 – 30” on the chalkboard.

Keaton: One hundred thirty-nine, then if you minus

thirty-nine, you’ll be back at one hundred. Um, and

then minus thirty. One hundred, then you go ninety,

eighty, seventy.

Mrs. K.: Oh, beautiful. You can even do that mentally.

Keaton: I did that.

By Anne M. Goodrow and Kasia Kidd

Anne M. Goodrow, agoodrow@verizon.net, teaches elementary mathematics methods courses at Rhode Island College in

Providence. She is interested in children’s mathematical thinking and preservice and in-service teacher development. Kasia

Kidd, kiddk@lincolnps.org, has taught for more than thirty

years, first as a special educator and currently as a secondgrade teacher at Lincoln Central Elementary in Lincoln, Rhode Island. She is interested in how

children’s oral explanations of their reasoning support the development of their thinking.

74

Mrs. K.: You did that. You did it mentally, and you

didn’t even use the number grid.

Winston shares next. He reads aloud how he has

made seventy, and Mrs. K. writes his expression on

the chalkboard: “1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + 9 +

10 + 20 + 10 – 10 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 1 – 1.”

Mrs. K.: Do you want to explain this one to us?

Winston: Well, my grandpa told me a trick. You

add the one with the nine, the eight and the two, the

three and the seven. [He draws a line connecting

the 1 and the 9 to make a 10.]

Mrs. K. [to the class]: Do you see how he made that

line there?

Mrs. K. [to Winston]: You see how you showed us

how the one and the nine go together and make a

ten? Could you do it for the other numbers you are

combining so we can see?

[Winston connects the 2 and 8, 3 and 7, and 4 and 6.]

Winston: It equals ten plus ten from here [pointing

to 1 and 9, 2 and 8. He then counts aloud.] “One,

two, three, four, five” [as he writes] “10 + 10 +

10 + 10 + 10” [under the long expression].

Winston: Then plus a five. So that equals five tens [plus

5]—equals fifty-five. And the fifty-five plus twenty

equals seventy-five. Seventy-five plus ten equals eightyfive. Minus ten equals seventy-five. Minus one, minus

Teaching Children Mathematics / September 2008

Copyright © 2008 The National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, Inc. www.nctm.org. All rights reserved.

This material may not be copied or distributed electronically or in any other format without written permission from NCTM.

one, minus one, minus one, minus one. Minus five

ones. Minus ten and minus five ones equals seventy.

Dr. A: What do people think about what Winston did?

Alex: He added one plus two, plus three, plus four,

but he knew he could make them all ten by adding

the 1 to the 9, the 2 to the 8, the 3 to the 7, the 4 to the

6. Then [he added] the 5 is by itself. Then you still

have the 10. And that’s ten, twenty, thirty, forty, fifty,

fifty-five … plus twenty equals seventy-five, plus ten

equals eighty-five, minus ten equals seventy-five,

minus one equals seventy-four, minus one equals

seventy-three, minus one equals seventy-two, minus

one equals seventy-one, minus one equals seventy.

Dr. A: Neat. So it really is helpful to know how to

make ten, isn’t it?

Mrs. K.: That making ten idea. Look at this. That

kind of reminds me of Keaton’s because he told me

that 139 minus 39 would give me what?

Children: One hundred.

Mrs. K.: Now I’ve got one hundred minus thirty

equals seventy. Does anybody see a ten in there?

Gianna?

Gianna: Thirty and seventy and a hundred.

Mrs. K.: And one hundred, right? So, that thirty and

seventy makes …?

Gianna: One hundred.

Mrs. K.: So, three tens and seven tens make …?

Gianna: One hundred.

Mrs. K.: And that’s the same as? Ten?

Gianna: Tens.

Mrs. K.: Ten tens. Exactly right.

A few minutes later, Maggie takes her turn sharing: “One hundred minus ten, minus twenty.”

“Minus twenty,” Mrs. K. repeats as she writes on

the chalkboard.

Mrs. K.: You want to tell us about that one?

Maggie: I knew one hundred minus thirty equals

seventy, but instead of using the thirty, I [changed]

it to one hundred minus ten. I knew twenty plus ten

equals thirty. So I did the minus ten, and then I did

the minus twenty.

Mrs. K.: Nice going. You know what Keaton said

as soon as you went up there to talk about it? What

did you say?

Keaton: I said, “It’s just like mine.”

Mrs. K.: He said, “It’s just like mine.”

Maggie: All of us who shared have something that’s

the same—Keaton, Winston, Jailene, me—we all

have something that has to do with tens.

Mrs. K.: Exactly. You do. You all have something

that has to do with tens. That’s great.

Teaching Children Mathematics / September 2008

Counting School Days

Counting the days of school is a popular routine in

many elementary mathematics classes. It is often

used only as a counting and grouping activity, and

on the hundredth day of school, the children bring

collections of one hundred objects to school. The

intention is to help them develop an understanding

of place value. Mrs. K.’s classroom is no exception

in this regard, but it is an exception when her students break apart the day’s number to create their

own equivalent numerical expressions.

What do the children learn about place value by

decomposing numbers in this activity? What does

their teacher learn about the children’s mathematical thinking when they share? How does Mrs.

K. respond to their sharing? How does she help

her students move forward in their mathematical

thinking? This article looks at the events that took

place on day 70 of the school year to illustrate how

decomposing numbers can help children construct

their understanding of place value.

Thus far in their sharing, we learned that

Keaton can count back by tens from one hundred

with ease, although we do not know if he can do

so from a number that does not end in zero. We

saw that Winston is very interested in numbers and

how they combine. He and other children know

pairs of numbers that equal ten, and when Winston

shares and Mrs. K. responds, the students see

that making tens can be helpful when combining

a string of single digits. Mrs. K. also pointed out

to the children that just as three ones plus seven

ones equal ten ones, three tens plus seven tens

equal ten tens. She helps the children extend

what they know about making ten by adding

ones to making one hundred by combining ten

tens.

Tyler shares

As the class continues, place value and ways to

make ten remain the focus of the discussion.

Tyler: Fifty-seven plus thirteen.

Mrs. K.: This is one I’d like you guys to talk to

each other [about]—you’re going to talk to your

partner. Now listen carefully. I look at the number

seventy, and I look at that, and I think “Oh, I need

to have seven tens there.” Now look at what Tyler’s

got. He’s got a fifty, so that’s five tens, and then

he’s got a thirteen, so I see another ten there. So

that’s five, six tens. So I’m just wondering, where’s

that other ten? Why don’t you talk to your partners

about that?

75

A buzz of children’s voices fills the room. One

girl says to her partner, “Fifty plus a ten would

equal sixty. And then seven plus a three will equal

another ten. That would equal seventy.” Here Mrs.

K. has used a “turn and talk” technique to involve

everyone in the mathematics; she wants everyone to

be thinking about ten. She makes explicit that fifty

has five tens and thirteen has one ten, although, in

retrospect, she might have first asked the children,

“How many tens does fifty have?” or “What does

the five in fifty mean?” before telling them that

fifty has five tens. Nonetheless, highlighting the

fact that seventy has seven tens, fifty has five tens,

and thirteen has one ten and asking the children

to find the remaining ten communicates to them

the importance of tens in our number system.

Mrs. K.: All right. Who would like to, who

would like to explain that to us? Liza, what’s

your thought?

Liza: Fifty plus the ten equals sixty, and the

seven plus the three is another ten. And that

equals seventy.

Getting “unstuck”

As the discussion continues, Tyler, the boy who wrote

“57 + 13,” encounters difficulty explaining how he

knows that fifty-seven plus thirteen equals seventy.

Mrs. K. gently supports and guides him through his

explanation, helping Tyler to clarify his thinking and

at the same time reinforcing mathematical concepts.

Tyler: You know, like the five, the fifty-seven and

the thirteen, so I added the thirteen, and then I

added up seven, so then I went [he stops talking

and is quiet].

Mrs. K.: So you had this [she writes “57 + 13”],

and you wanted to check and see if it really was

seventy?

Tyler: Yeah.

Mrs. K.: So how did you start?

Tyler: I started with the fifty-seven.

Mrs. K.: OK.

Tyler: So then I went up—fif—no, I went up thirteen again, and then …

Mrs. K.: You went up thirteen. What do you mean

by that?

Tyler: I mean that when I was at fifty-seven, I went

up thirteen.

Mrs. K.: Were you using a number grid [hundreds

chart]?

Tyler: Yeah.

Mrs. K.: Go on.

76

Tyler: So then I went up thirteen again, and I

thought to myself, that didn’t equal seventy. So I

went back thirteen.

Mrs. K.: I’m a little confused. So you’re saying

fifty-seven plus thirteen is not equal to seventy, or it

is equal to seventy?

Tyler: It is.

Mrs. K.: It is. And how do you know for sure?

Tyler: Because thir—no.

Mrs. K.: You want to start with your fifty-seven?

Tyler: Yeah.

Mrs. K.: Okay. So I’m at fifty-seven, and what

would you like to add to it first?

Tyler: I added a, a ten.

Mrs. K.: All right. So fifty-seven plus ten got you

where?

Tyler: Got to … [pause]… Got to sixty-seven.

Mrs. K.: Did this help? [She has drawn “57” and

“67” in boxes, vertically, as they are on the hundreds grid and has written “57 + 10 = 67.”]

Tyler: Yeah.

Mrs. K.: Now he’s at sixty-seven. So now what are

you going to do?

Tyler: So then I plus. [Tyler is silent.]

Mrs. K.: Where did this ten come from?

Tyler: It came from the fifty-sss—from the thirteen.

[Mrs. K. points to the 1 in 13.]

Mrs. K.: So this one stands for your ten, right? So,

what have you got left?

Tyler: Three.

Mrs. K.: Three. And sixty-seven plus three more

makes …?

Tyler: Equals seventy.

Mrs. K.: Nice job.

As we examine Mrs. K.’s words and actions, we

note that first she asked Tyler for clarification: “You

went up thirteen. What do you mean by that?” She

then asked about the tool he may have used. Moving “up” thirteen suggests using a number line or

number grid (hundreds chart). When Tyler was confused, Mrs. K. suggested that he start at fifty-seven.

Tyler chose to add ten but could not go any further

until Mrs. K. drew a visual—two boxes arranged

vertically and labeled “57” and “67.” After Tyler

said, “Sixty-seven,” she wrote, “57 + 10 = 67.” In

the discussion about where the ten came from, Mrs.

K. reinforced place value. The ten is part of the

thirteen, and now Tyler knows he has three left to

add to sixty-seven. Mrs. K’s scaffolding has helped

Tyler, and very likely other children, to think about

place value (the meaning of the one in thirteen) as

well as how to add one ten to a number.

Teaching Children Mathematics / September 2008

Adding tens and adding to

make ten

The class continues as children share their ways to

make seventy and Mrs. K. asks for one more child

to explain where the seven tens are in 57 + 13.

Mrs. K.: Is there one more person who can tell me

where the seven tens are? Okay, let’s see. G

­ abriella.

Gabriella: Um … um … I took away the three and

the seven for a while. And then …

Mrs. K.: So you ended up with a fifty and a ten.

Gabriella: Umhmm, and I knew that a fifty and a

ten would equal sixty.

Mrs. K.: Umhmm.

Gabriella: Then plus three plus seven would equal,

would equal ten. So fifty plus ten will equal sixty

plus a ten will equal, will equal seventy.

Mrs. K: Nice going. So you broke that fifty-seven and

that thirteen into fifty, ten, three, and seven. Nice job.

Dr. A: So she knew how to add tens. She knew that

seven and three made ten.

Mrs. K: That’s handy.

Child: We have it on our desks from you. That’s

why me and Jailene went to get it.

Mrs. K: Oh, because it’s …

Child: Ways to make ten.

Gabriella: Equals ten.

Mrs. K.: And that’s pretty important …. It came in

useful when …

Gabriella: Winston.

Mrs. K.: Winston. When Keaten needed seventy;

one hundred minus thirty.

Child: One hundred thirty-nine minus thirty-nine.

Mrs. K.: He had that one hundred minus thirty right

in there.

Dr. A: And when Winston had added all those

numbers.

Mrs. K.: And when Winston added all those numbers too. Nice job.

[Economopoulos et al. 1998, p. 40] and “The Name

Collection Box” in Everyday Mathematics [Bell

et al. 2002]), students have many opportunities to

look at how numbers are composed, and, in doing

so, they develop their understanding of the structure

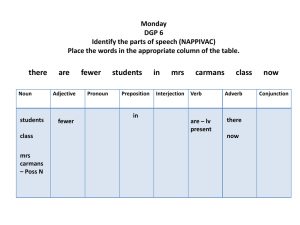

Figure 1

Examples of children’s expressions for 18 are from early in the school

year.

(a) Mrs. K. used the mathematical terms expanded notation and commutative property. She inserted parentheses to show how one student added fives

(Kidd 2005).

10 + 8 = 18 expanded notation [the teacher added the label]

18 + 0 = 18 0 + 18 = 18 cmoohivpopde (commutative property)

19 – 1 = 18

13 + 5 = 18

42 – 24 = 18

(2 + 3) + (2 + 3) + (2 + 3) + 3 = 18 [the teacher added the parentheses]

17 + 1 = 18

100 + 100 –100 + 100 – 80 – 20 – 3 – 7 – 3 – 7– 3 – 7– 3 – 7 – 3 – 7– 3 – 7– 3 –

7 – 3 –7 – 3 – 7 + 8 – 8 + 8 – 8 + 4 + 4

(b) The commutative property makes sense, and children remember the term

when they have used it in their work.

Gabriella, like Liza, sees that groups of ones,

in this case seven and three, can be added to make

ten. However, these children treat this sum of ten as

another group of ten. As Liza put it, “Fifty plus the ten

equals sixty, and the seven plus the three is another

ten.” Their discussion suggests that they see that ten

can be ten ones or one group of ten, an important

developmental step in understanding place value.

Decomposing the Number

of the Day

Through this classroom routine (entitled “Today’s

Number” in Mathematical Thinking at Grade 2

Teaching Children Mathematics / September 2008

77

of our number system as well as explore arithmetic

operations.

As the children break apart numbers, they work

with part-whole relationships. Part-whole relationships are often considered in the context of number concepts and conservation of number, as, for

instance, the different combinations that make a

certain quantity (e.g., 5 can be 2 and 3, or 1 and 4,

etc.). Our view of part-whole relationships includes

place value. Place value is more than identifying

the ones, tens, and hundreds columns. Understanding groups of ten grows out of children’s own logic

as they work with numbers in meaningful activities

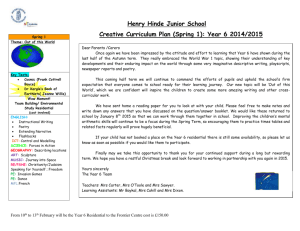

Figure 2

The constraint of using three addends

was given on day 94. This student first

decomposed the 4 and then the 90.

Figure 3

Here are five examples from day 108, when students were asked to

write expressions using subtraction in this format: ___ – ___ = 108. Some

children decomposed larger numbers, and others wrote story problems.

108

8,000 – 7,892

300 – 192

708 – 600

Heather has 109 dollars. She loses 4 quarters. How much money does she

have now?

Liza knows 110 Russian words. She forgets 2. How many Russian words

does she know?

78

such as decomposing numbers to make expressions

equivalent to the number of the day. Over time and

with many numerical experiences, children come

to understand the relationship between numbers

and groups of tens and ones (Burns 1993; Kamii

1985, 1989; Ross 1989), and the idea that a digit

can simultaneously represent a number of tens or a

number of ones (e.g., the 5 in 52 can represent five

tens or fifty ones).

How the activity evolves

A typical mathematics class, like day 70, begins

with children working individually in their mathematics notebooks to create mathematical expressions equivalent to a particular number. As the

children work, we circulate, ask questions, and

offer help if needed. Our goal during this time

is to encourage the children’s own mathematical

thinking. Questions can be general, such as, “How

did you think about that?” and “How does your

pattern work?” or more specific, such as, “What

will happen if you add another ten?” and “Is there

something you know about [another number] that

you can use to help you?”

Next, the class comes together, and the children

share and discuss their numerical expressions. Discussion is a critical component of the activity; children’s ideas are made public, and mathematics is

made explicit, as we saw in the vignette. We focus

the children’s attention on mathematical ideas that

otherwise may remain embedded within the children’s work. Although we have topics in mind, such

as place value, topics may also come from the children themselves. Discussion topics have included

the inverse relationship of addition and subtraction,

negative numbers, and, of course, place value.

Early in the year, few constraints are imposed on

the task. Very long expressions, such as the last one

in figure 1a, capture children’s interest; however,

children have to learn to keep track of their computation. They learn about chunking numbers to

subtract and about making zero; in one memorable

class, the children come to the conclusion that if

you subtract the same amount as you add (or vice

versa), the result is zero. Opportunities arise for

using mathematical language in context. Children

remember the commutative property, and it makes

sense to them, when it is connected to their own

work (see fig. 1b). As the year continues, Mrs. K.

provides mathematical constraints and challenges,

and the children’s work increases in sophistication

as their knowledge of our number system grows

(see figs. 2 and 3).

Teaching Children Mathematics / September 2008

We believe that children’s continued experiences

decomposing number as they keep track of their

school days encourages development of understanding place value as well as practice using the

number system. Such experiences may very well

provide a much-needed foundation for children’s

work with algorithms for addition and subtraction;

these algorithms can be viewed as particular ways of

decomposing to combine or separate numbers based

on place value. Such experiences provide additional

rewards, too. They support children in the quest to

learn mathematics meaningfully and well, in taking

risks, and in learning from one another.

References

Bell, Max, Jean Bell, John Bretzlauf, Amy Dillard, Robert Hartfield, Andy Isaacs, James McBride, Kathleen

Pitvorec, and Peter Saecker. Everyday Mathematics.

2nd ed. Chicago: Wright Group/McGraw Hill, 2002.

Burns, Marilyn. Mathematics: Assessing Understand-

Teaching Children Mathematics / September 2008

ing, Part 1. White Plains, NY:

Cuisenaire Co. of America. 1993.

Video.

Kamii, Constance. Young Children

Reinvent Arithmetic: Implications

of Piaget’s Theory. New York:

Teachers College Press, 1985.

———. Young Children Continue to

Reinvent Arithmetic (2nd Grade): Implications

of Piaget’s Theory. New York: Teachers College

Press, 1989.

Kidd, Kasia. “A New Routine for Name Collection Boxes.” TeacherLink 14, no. 1 (Fall 2005):

16–17.

Ross, Sharon. “Parts, Wholes, and Place

Value: A Developmental View.” Arithmetic Teacher 36 (February 1989):

47–51.

Economopoulos, Karen, Joan Akers, Doug

Clements, Anne Goodrow, Jerrie Moffet,

and Julie Sarama, eds. Mathematical Thinking at Grade 2. In Investigations in Number,

Data, and Space series. Menlo Park, CA:

Dale Seymour Publications, 1998. s

79