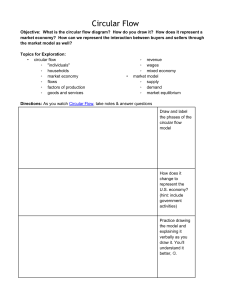

The Circular Economy: what does it mean for the waste and

advertisement