Common factors behind success or failure of innovations

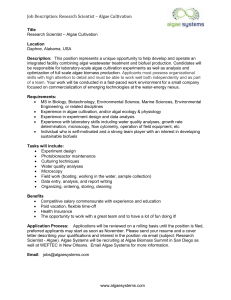

advertisement