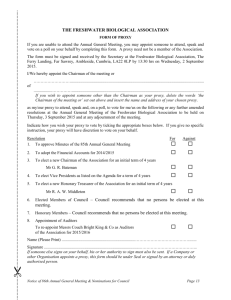

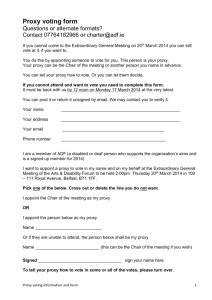

power of proxy - Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors

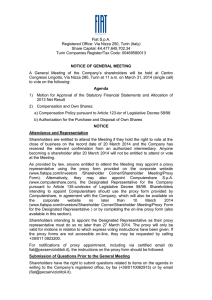

advertisement