Instruction in the New Literacies of Online Reading Comprehension

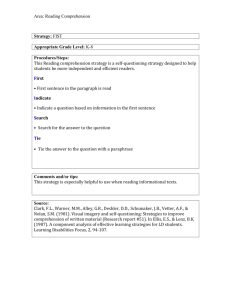

advertisement