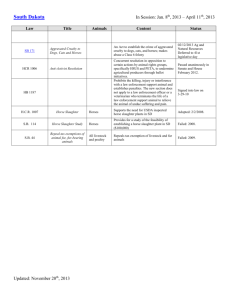

Number of Horses Slaughtered Annually

advertisement