Recent Experience from Germany – Philine Warnke.

advertisement

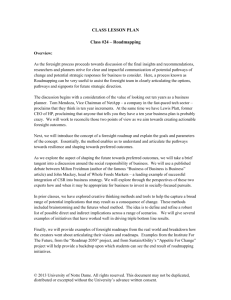

Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 1 EMBEDDING TRANSFORMATIVE PRIORITIES INTO THE STI LANDSCAPE EXPERIENCE FROM THE BMBF-FORESIGHT SYSTEM Author Philine Warnke1, Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research, Breslauer Str. 48, 76139 Karlsruhe, Germany, philine.warnke@isi.fraunhofer.de Keywords: Foresight, Priority Setting, Innovation policy, systemic transformation Summary The paper is addressing theme 1 and 2 of the FTA call for abstract in an integrated manner. We set out from the assumption that – due to the intrinsically systemic nature of the “grand challenges” - a key requirement for “orienting innovation systems towards global challenges” is to “build capacities for structural and systemic transformation”. We argue that in the case of Foresight for RTI priority setting this requires “transformative priorities” that are different not only in content but also in type from traditional thematic RTI priorities. We outline characteristics of such priorities and discuss in how far Foresight is in a position to underpin their generation and implementation. As an empirical case we investigate the follow-up activities of the BMBF-Foresight process that was carried out in Germany from 2007-2009 to propose cross-cutting long-term priorities for STI policy in Germany. Since then BMBF has launched a set of instruments aiming to underpin the implementation of the Foresight’s findings. Together these activities are forming a learning “Foresight System” which is continuously monitoring and acting upon the evolution of the RTI landscape in a systematic manner. The main elements of the Foresight system are: strategic dialogues with key actors inside and outside the ministry a monitoring system observing the evolution of the transformative priorities an integrated evaluation process. The key challenge for this learning Foresight system is to embed the cross-cutting and systemic priority fields that were proposed by the Foresight process into today’s institutional context which is organised around classical technology lines. Within BMBF, actors need to be aligned across several departments each following its own thematic strategy. But also in the wider STI landscape disciplinary and institutional silos have to be transcended. The paper outlines the concept of the Foresight follow-up activities and discusses the challenges encountered and impacts achieved to date. We conclude with some more general lessons on the potential role of Foresight in RTI priority-setting for the governance of systemic change in innovation trajectories. In particular we emphasise that to 1 Fraunhofer Institute of Systems and Innovation Research ISI, Karlsruhe THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 2 address structural transformation through STI priority setting2 we need to find ways to address the institutional dimensions of these transitions in our FTA capacity building. Otherwise it does not seem likely that STI programmes will pay more than lip service to the “grand challenges” of our time. 1. Introduction – transformative RTI priorities For some time now, the aim of “orienting innovation systems towards global challenges”3 has become an important driver of research, technology and innovation (RTI) policy on national and transnational level around world. On the European Union level, the mission oriented turn was first outlined in the “lund-declaration”4 where it was clearly stated that “European research must focus on the Grand Challenges of our time moving beyond current rigid thematic approaches”. In the following policy documents such as the Europe2020 Strategy and the Innovation Union Initiative5 the demand driven approach was subsequently refined. Already in the Lund-Declaration it was recognised that realising a demand oriented innovation policy strategy will require much more than just feeding new topics into the established structures of RTI policy making but include new types of priorities as well as new approaches to implementation. The reason for this difference in kind is the aim of actually making an impact on socio-technical trajectories whereas previous thematic approaches were primarily targeting competitiveness in view of other players. Impacting on the complex interplay of technology and society in order to address global challenges however is much more difficult than picking the most promising technologies. Through in depth analysis of historical and contemporary cases, science and technology studies (STS) have shown that new demands and solutions emerge through a complex multi-level co-evolution of societal and technological changes (Bijker, Law 1997). This process cannot be influenced by acting on one angle alone in a top down manner. If co-evolutionary trajectories can be modulated at all, it is through experimenting around the nexus between variation and selection which are both socio-technical processes (Rip, Schot 2002). In particular major “structural and systemic transformations” in the way we fulfil societal needs as they are required for addressing challenges such as sustainability, health and security can only be facilitated through “transformative innovation” (Steward 2008) that is aligning social and technological changes. Therefore, transformative RTI priorities that allow us to “turn problems into solutions and opportunities” as emphasised in the Innovation Union Initiative are likely to differ in several characteristics from traditional thematic RTI priority lines. In particular the following elements seem to be emerging as characteristic for transformative priorities: 2 As requested e.g. by the Lund Declaration and Europe2020 strategy 3 FTA call text 4The Lund Declaration 2009. Europe must focus on the Grand Challenges of our Time. The Lund Declaration - se2009.eu 5 COM(2010) 546 final. Europe2020 Flagship Initiative Innovation Union THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 3 Shared Transformative priorities will not be defined in a top-down manner but through bottom-up participatory processes. As emphasised by the Lund declaration: “Identifying and responding to Grand Challenges should involve stakeholders from both public and private sectors in transparent processes taking into account the global dimension” Inclusive New actor groups such as citizens, technology users and social entrepreneurs will have a major role in defining and implementing transformative priorities. This is not only due to the need to democratise priority setting and enhance its transparency. Rather these actors are increasingly being recognised as relevant drivers of transformative innovation. (von Hippel 2006). Hybrid: Transformative priorities will be hybrid in two respects: They transcend disciplinary boundaries in particular between social sciences and humanities on the one hand and engineering and natural sciences on the other and address socio-technical issues in a transdisciplinary manner. At the same time they will extend the notion of RTI from research labs and engineering offices into society to include social and organisational innovation. Experimental/tentative: Transformative priorities will have clear goals. Nevertheless the solution adopted to achieve these goals will rarely be fixed upfront but rather evolve through the implementation process. Collective experimentation with different sociotechnical configurations will be at the core of the implementation (Joly et al. 2010). Support platforms for collective experimentation like living labs, collective visioning and socio-technical scenario building will play a key role as enablers of transformative innovation. (Extra)-systemic Transformative priorities will adopt the systemic perspective required to modulate co-evolutionary trajectories. At the same time they will allow for moving beyond intra-systemic optimization of existing socio-technical trajectories. They will be based on recognition of the possibility of “change in the conditions of change” (Miller 2007b) and – if required - target structural change of existing paradigms. Glocal Transformative priorities may be adopted across several regions, nations as well as on European or event global level. Nevertheless they will have to be tailored to each specific socio-cultural and sectoral context through appropriation processes. Such transformative priorities require new processes for definition and implementation. EU policy strategies such as the Innovation Union Initiative have recognised this requirement. Instruments such as the “innovation partnerships” aim to “build capacities for structural and systemic transformation” not only by taking up new problem driven topics but also by adopting new approaches to their implementation. THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 4 2. Implications for Foresight RTI priority setting has been one of the most prominent application domains of Foresight for quite some time. Many countries and regions around the world use Foresight to support RTI priority setting in one way or another (Cuhls, Salo 2003). Accordingly, the rise of transformative priorities will impact on Foresight practice. We argue that Foresight has a role to play in both the generation and implementation of transformative priorities. 2.1 Generation of transformative Priorities How is Foresight positioned to generate transformative priorities with characteristics like the one outline above? The following hypotheses can be derived from recent Foresight theory and practice: Foresight understood as “structured stakeholder dialogue on complex futures”6 is well suited to support the generation of shared priorities. As a systemic innovation policy instrument it has long been recognised for its ability of “wiring up” innovation systems (Martin, Johnston 1999) by way of creating shared visions and learning platforms (Smits, Kuhlmann 2004). Accordingly, the ability of Foresight to support joint programming has often been emphasised. The Lund declaration and the Innovation Union Initiative both make explicit reference to Foresight as a means for creating shared and trusted priorities. Foresight, according to the most common definitions7 is a participatory process. Enhancing the transparency and democratising RTI priority setting is one of its foremost objectives (Da Costa et al. 2008). Nevertheless in its current practice RTI oriented Foresight is less accustomed to direct involvement of citizens or innovation users. Only in few cases such as the German Futur exercise direct involvement of citizens into RTI priority setting has been practiced. Usually, stakeholder involvement is realised by inviting representatives of organisations such as NGOs or consumer associations. Adopting more directly inclusive forms of participation as a means to underpin collective experimentation requires not just a different set of participants but also a careful adaptation of the methodological framework. Experience from related communities of practice such as participatory Technology Assessment (Steyaert et al. 2006) needs to be exploited. In its definition Foresight is incorporating the systemic perspective. Most Foresight practitioners emphasise the holistic approach to exploring system dynamics. The ability to integrate diverse perspectives into collective intelligence is at the heart of the Foresight methodological framework. Accordingly defining hybrid socio-technical priorities that align social innovation and key technologies 6 Fraunhofer ISI definition 7 C.f. e.g. the FORLEARN online Foresight guide http://forlearn.jrc.ec.europa.eu/guide/1_why-foresight/characteristics.htm THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 5 as well as diverse disciplines into solutions for the grand challenges should come natural to Foresight. However, in practice in particular in many cases of “Technology Foresight” substantially less attention is paid to investigating the societal dimension of change than the technological one (Warnke, Heimeriks 2008). Many Foresight exercises aim at consensus and different trajectories within existing systems rather than recognising extra-systemic change. Nevertheless some Foresight methods such as “rigorous imagining” (Miller 2007a) or causal layered analysis (Inayatullah 2009) explicitly address structural and systemic transformation and questioning of dominant narratives. Others target open ideation and the break-up of lock-in into established innovation trajectories (Könnölä et al. 2007). As a participatory process of exploring alternative futures Foresight is ideally suited to support experimental approaches to RTI priority implementation. Collective processes of visioning, socio-technical scenario building and roadmapping may become a core element of collective experimentation. RTI Foresight however, needs to re-learn this experimental capability as in the era of thematic approaches Foresight processes often ended with lists of priorities. To sum up, it seems that Foresight has substantial potential to contribute to the generation of transformative RTI priorities when fully exploiting of its theoretical and methodological foundations. A recent review of current Foresight exercises aiming at national level RTI priority setting revealed several examples of recent Foresight processes that came up with suggestions for RTI priorities with a transformative character.8 In table 1 some of these priority areas are listed. Priority area Source Core approach ProductionConsumption2.0 BMBF-Foresight-Process Systemic socio-technical innovation towards sustainable patterns of production and consumption. Focus on critical bifurcations of production and consumption. Including methods for moderating and sustainability transitions. Human-Technology Coop- BMBF-Foresight-Process Transdisciplinary research on 8 Paper for the EU SSH expert group „Europe and the world 2030/2050“, to be published as part of the documentation in 2011 THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 6 eration new formations of humans and technology from individual level up to socio-cultural perspective. Living spaces of the future BMBF-Foresight-Process Concepts for urban and rural space accommodating the changing requirements of future generations Sustainable resource man- FNR Luxembourg Foresight Sustainable territorial devel- agement Process9 opment in urban and rural areas, integrative and holistic understanding of energy and material flows in Luxembourg, agro-systems management, ecosystems and biodiversity Local cycles and future of Foresight.fi10 Exploring possible futures for countryside the countryside such as local cycles of production, consumption or wellbeing and recreation Sustainable transport and Forsk201511 Sustainable transport systems infrastructure Better life space – space for and solutions Forsk2015 Progressive coupling of urban life and growth development, physical planning and social progress Changing lives Forsk2015 Fundamental knowledge of the opportunities and needs of different age groups 9Luxembourg FNR FORESIGHT http://www.fnrforesight.lu/ - THINKING FOR THE FUTURE TODAY. 10 http://www.foresight.fi/ 11 The Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation RESEARCH2015 – A Basis for Prioriti- sation of strategic Research http://www.forsk2015.dk THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 7 Energy systems of the fu- Forsk2015 ture Developing competitive, energy efficient and sustainable energy systems that can satisfy future energy demands and environmental requirements Bio-resource based produc- Forsk2015 tion The research is directed at the health and wellbeing of animals and people and at the interaction of bioproduction with, and impacts on, the surrounding society, environment and biological diversity. Two related transitions: Netherlands Horizon Scan12 Creating and utilizing space Making good use of limited space and possibly make new space available. New roles for urban and rural space. Accelerating the develop- NL Horizon Scan New forms of extracting, stor- ment of new energy ing energy and transition to sources adequate infrastructures Infrastructures for the fu- NL Horizon Scan ture How can we shape infrastructural facilities so that they fit better with new and future desires and demands? Infrastructural breakthrough through new coupling of hard and soft infrastructure. Robotics and interconnectivity NL Horizon Scan Implication of robotics and intelligent systems for humans society and social living 12 Horizon Scan Report 2007: Towards a Future Oriented Policy and Knowledge Agenda. www.horizonscan.nl THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 8 Engineerable human NL Horizon Scan Trans-disciplinary research on issues of changing human nature and societal responses in the face of medicotechnical research What does the “greying” of NL Horizon scan society mean? Manufacturing on demand Understanding socio-cultural change in an aging society UK TIF13 Distributed localised manufacturing of personalised products with rapid manufacturing technologies and new business and service models The energy transition UK TIF Decarbonisation of energy. New sources, new storing new distribution facilities new services. Smart Infrastructure UK TIF Intelligent transformation of Electricity and other infrastructures with sensors and meters to meet future demands (in particular new energy sources and resource efficiency) 2.2 Embedding of transformative priorities In the previous section we have discussed the requirements for Foresight arising from the need to generate transformative priorities. These requirements however may be only the tip of the iceberg. The other part of orienting RTI systems towards global challenges i.e. the embedding of RTI priorities into strategic processes across the RTI system may be posing challenges that are even more substantial. 13 Foresight Horizon Scanning Centre, Government Office for Science (2010): Technology and Innovation Futures UK Growth Opportunities for the http://www.bis.gov.uk/foresight/our-work/horizon-scanning-centre/technology-andinnovation-futures THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) 2020s. Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 9 Foresight practitioners have emphasised for quite some time that embedding Foresight findings into strategic processes of actors does require a dedicated effort. The notion of “adaptive Foresight” (Eriksson, Weber 2008) has been proposed to characterise Foresight processes that foresee specific measures for translating the findings of the collective process into the decision making structures of different actor organisations. This requirement however may be much more challenging in a situation of shift towards transformative priorities. As outlined above, the notion of mission-oriented RTI policy implies not only a different content but also a different kind of implementation processes. In particular in a phase of transition of policy paradigms, transformative priorities need to be embedded into a RTI landscape that is structured according to the previous paradigm. Universities, research institutes, industrial R&D departments, technology assessment institutions, NGOs and last but not least ministries and funding agencies are structured around thematic technological realms. In particular joint research of social sciences and humanities and technology and natural sciences is a rare phenomenon. Only very few cases of experimentation around aligned social and technological innovation patterns exist. In such a fragmented landscape, aligning forces around systemic and hybrid socio-technical RTI arenas requires special efforts for embedding Foresight results. Whereas previously, prioritised list of “key technologies” with the highest promise of increased competitiveness could easily be fed into the funding programme of the respective RTI policy units and in turn be addressed by the respective RTI departments, transformative priorities may require a more intense and exploratory adaptation process. 3. The case of the BMBF-Foresight-System To illustrate the reflections above, we will now discuss recent experience from the follow-up activities of the BMBF-Foresight-Process that was carried out in Germany from 2007-2009 with the objective of proposing long-term priorities for German RTI policy (Cuhls et al. 2009a). This Foresight-Process set out from a classical thematic approach and mapped out current perceptions of emerging developments within established innovation fields through in depth scanning of expert judgements (Cuhls et al. 2009b). However, in a second phase these findings were subjected to a crosscutting synthesis with a strong view to future socio-economic challenges. In this analysis a set of crosscutting and systemic long-term priorities for German innovation policy emerged: the “new future fields” (Cuhls et al. 2010). In particular three of these cross-cutting priority fields can be characterised as “transformative” in the sense outlined above: “humantechnology cooperation”, “future living spaces” and “ProductionConsumption2.0” (c.f. table 1). In its report the Foresight team emphasised that the different types of findings required different types of follow-up activities. This was confirmed when - in the Foresight implementation phase - the findings were discussed with BMBF actors from different departments and units. Whereas the findings in the established fields sometimes met criticism as the departments’ actors had a different view on their own field’s emerging issues, the cross-cutting “new futures fields” were almost unanimously welcomed. In particular BMBF actors recognised the “birds-eye view” that they felt added substantial value to their own perspective and took up relevant issues that could not be addressed adequately in the existing organisational structure. THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 10 At the same time, the outcomes within the established innovation arenas could easily be fed into the strategic processes of the BMBF departments through personal discussions with the responsible actors who compared them with their own assessment and took them up when appropriate. The “new future fields” however required a substantial “boundary spanning” effort. Repeatedly, the BMBF Foresight department, together with the Foresight team discussed the cross-cutting findings with actors from different departments and different levels individually and in small groups in order to generate shared ground for implementation strategies. Quickly it became clear that a simple translation of the new perspectives into funding programmes would not justice to the cross-cutting nature of the transformative priorities. Instead it was felt that appropriate platforms for tackling the new realms needed to be established within BMBF but also in the wider RTI landscape. In order to further underpin this proactive reconfiguration process towards the new priority fields, BMBF launched two complementary activities: Strategic dialogues with key actors across the RTI landscape in order create a shared understanding of the new future fields and prepare the ground for further implementation14. A “tracking system” for observing the evolution of the “new future fields” and identifying needs for additional support measures. For assessing a potential future innovation arena that is not yet established, classical scientometric methods such as patent or bibliometric analysis cannot be directly applied. Accordingly, the system deploys an innovative semi-quantitative assessment approach which is based on a morphological box with four different dimensions which are continuously observed and assessed through specific methods in a half-yearly status report. The implementation of these activities was part of a general intention of the BMBF Foresight department to embed Foresight within BMBF as a continuous activity where phases of scanning, implementation, observation and again scanning follow each other in an integrated and systematic manner (Bode, Beyer-Kutzner 2010). Figure 1 shows the twofold role of the monitoring system within the Foresight system: On the one hand it is underpinning the evolution of the systemic transformative priorities by continuously monitoring their progress and proposing supportive interventions if required. At the same time it is supporting the preparation of the subsequent scanning phases. 14 The strategic dialogues are introduced in the contribution of Lohr et al in this conference THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 11 Figure 1: BMBF Foresight System (Bode, Beyer-Kutzner 2010), p.78. The design of this “Foresight system” was supported by the Foresight evaluation team15 that had closely observed the Foresight and implementation activities and continuously monitored their impact. Currently, the follow-up activities are focussing on the two transformative “future fields”: Human-Technology-Cooperation and ProductionConsumption2.0. Several dialogues inside and outside BMBF have taken place and the monitoring system has delivered its first status report. Whereas all indicators are pointing towards the continued need for both the systemic innovation priorities, the observations confirm the hypothesis above: The main challenge to putting transformative innovation priorities into practice is the strong embedding of established thematic perspectives into the very structure of RTI landscape across all levels and realms. In particular integrated research across social sciences and humanities on the one hand and natural science and engineering on the other, which is required for both cross-cutting priority fields, requires institutional reconfigurations. Through its multi-facetted Foresight system BMBF is progressing on the road towards implementation of the transformative priorities in a tailored manner. In the case of Human-Technology-Cooperation a department was founded that is dedicated to supporting RTI activities in this field. In the case of ProductionConsumption2.0 a consensus across the diverse relevant departments concerned with environment, manufacturing, services, materials and bioeconomy is under way. Aspects of the “living spaces” were fed into the High-TechStrategy. Conclusions The experience from the BMBF-Foresight’s follow-up activities suggests that in order to address structural transformation through demand oriented RTI priority setting, as it is 15 ITA Institut für Arbeit und Technik, Kaiserslautern THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 12 requested by the “Lund Declaration” and the Europe2020 Strategy, we need to tackle the institutional dimensions of these transitions in our FTA capacity building. Otherwise it does not seem likely that RTI programmes will pay more than lip service to the “grand challenges” of our time. Foresight may well have a role to play in this transition process provided that the development towards adaptive and embedded Foresight is further extended and its methodological potential is fully exploited. It seems that the BMBF approach of setting up an embedded Foresight system, where scanning is complemented by strategic dialogues and a tracking system in a systematic and continuous manner could be a substantial step in this direction. References Bijker, W.E.; Law, J. (1997): Shaping technology / building society. Studies in sociotechnical change, Inside technology, Cambridge/Mass.: MIT Press. Bode, O.; Beyer-Kutzner, A. (2010): Der BMBF-Foresight-Prozess: Schwerpunkte in Technologie und Forschung in Deutschland. In: Hauss, K.; Ulrich, S.; Hornbostel, S. (eds.): iFQ-Working Paper No. 7 | September 2010. Foresight between Science and Fiction. pp. 73-79. Cuhls, K.; Salo, A. (2003): Preface - technology foresight - past and future. In: Journal of forecasting, 22 (2-3), pp. 79-82. Cuhls, K.; Beyer-Kutzner, A.; Ganz, W.; Warnke, P. (2009a): The methodology combination of a national foresight process in Germany. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 76 (9), pp. 1187-1197. Cuhls, K.; Ganz, W.; Warnke, P. (eds.) (2009b): Foresight-Prozess im Auftrag des BMBF. Etablierte Zukunftsfelder und ihre Zukunftsthemen. Available at: http://www.isi.fraunhofer.de/isi-de/v/projekte/bmbf-foresight.php Cuhls, K.; Warnke, P.; Ganz, W. (eds.) (2010): Foresight Process on behalf of the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research: New Future Fields. Available at: http://www.bmbf.de/en/12673.php Da Costa, O.; Warnke, P.; Cagnin, C.; Scapolo, F. (2008): The impact of foresight on policy-making: insights from the FORLEARN mutual learning process. In: Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 20 (3), pp. 369-387. Eriksson, E.A.; Weber, K.M. (2008): Adaptive Foresight: Navigating the complex landscape of policy strategies. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 75 (4), pp. 462-482. THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 13 Inayatullah, S. (2009): Causal Layered Analysis: An Integrative And Transformative Theory And Method. In: Glenn, J.C.; Gordon, T.J. (eds.): The Millenium Projekt. Futures Reseach Methodology V 3.0. p. Chapter 35. Joly, P.-B.; Rip, A.; Callon, M. (2010): Re-Inventing Innovation. In: Arentsen, M.J.; Van Rossum, W.; Steenge, A.E. (eds.): Governance of Innovation: Firms, Clusters and Institutions in a Changing Setting. Cheltenham [u.a.]: Elgar, pp. 19-32. Könnölä, T.; Brummer, V.; Salo, A. (2007): Diversity in foresight: Insights from the fostering of innovation ideas. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 74 (5), pp. 608-626. Martin, B.R.; Johnston, R. (1999): Technology Foresight for Wiring Up the National Innovation System: Experiences in Britain, Australia, and New Zealand - Technological Forecasting and Social Chang. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 60 (1), pp. 37-54. Miller, R. (2007a): Futures literacy: A hybrid strategic scenario method. In: Futures, 39 (4), pp. 341-362. Rip, A.; Schot, J.W. (2002): Identifying loci for influencing the dynamics of technological development. In: Sorensen, K.; Williams, R. (eds.): Shaping technology, guiding policy : Concepts, spaces and tools. Elgar Publ. Ltd., Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA,USA, pp. 155-172. Smits, R.; Kuhlmann, S. (2004): The rise of systemic instruments in innovation policy. In: International Journal of Foresight and Innovation Policy, 1 (1/2), pp. 4-32. Steward, F. (2008): Breaking the Boundaries. Transformative Innovation for the global good. NESTA. Steyaert, S.; Lisoir, H.; Nentwich, M. (eds.) (2006): Leitfaden partizipativer Verfahren Ein Handbuch für die Praxis: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press. von Hippel, E. (2006): Democratizing Innovation: The evolving phenomenon of User Innovation. In: Kahin, B.; Foray, D. (eds.): Advancing Knowledge and the Knowledge Economy. pp. 237-255. Warnke, P.; Heimeriks, G. (2008): Technology Foresight as Innovation Policy Instrument: Learning from Science and Technology Studies. In: Cagnin, C.; Keenan, M.; Johnston, R.; Scapolo, F.; Barre, R. (eds.): Future-Oriented Technology Analysis. Strategic Intelligence for an Innovative Economy. Springer, pp. 71-87. THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS) Fourth International Seville Conference on Future-Oriented Technology Analysis (FTA) FTA and Grand Societal Challenges – Shaping and Driving Structural and Systemic Transformations SEVILLE, 12-13 MAY 2011 14 THEME: (BUILDING FTA CAPACITIES FOR SYSTEMIC AND STRUCTURAL TRANSFORMATIONS)