Anscombe on Practical Inference

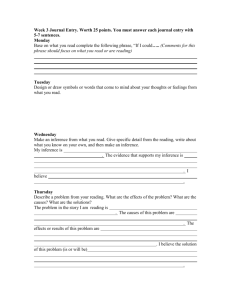

advertisement