The Panama Canal

advertisement

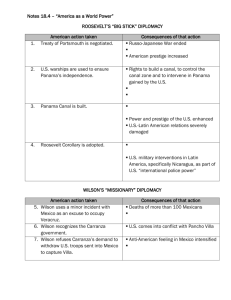

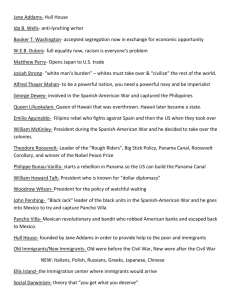

Copyright Bruce Lesh What is President Theodore Roosevelt doing in his autobiography? • Truth • A lie • A half-truth • An exaggeration • Obfuscation (hiding the truth) Copyright Bruce Lesh President Theodore Roosevelt “No one connected with the American Government had any part in preparing, inciting, or encouraging the revolution, and except for the reports of our military and naval officers, which I forwarded to Congress, no one connected with the American government had any previous knowledge concerning the proposed revolution…” “From the beginning to the end our course was straightforward and in absolute accord with the highest of standards of international morality…I did not lift my finger to incite the revolutionists…I simply ceased to stamp out the different revolutionary fuses that were already burning…” ~~~~~Theodore Roosevelt Copyright Bruce Lesh Panama Canal Timeline 1850 Clayton-Bulwer Treaty : The United States and Britain agree to seek an independent canal. 1898 20-year French effort to build a canal fails after 300 million dollars and thousands of lives are lost 1901 Hay-Poncefote Treaty: British relinquish their rights to construct a canal 1903 : Convinced by French construction manager, Philippe Bunau-Varilla, the United States agrees to construct a Colombian canal rather than one in Nicaragua. 1903 1903 Hay-Herran Treaty: United States and Columbia agree to lease the United States a strip of land for 100 years for $40 Million. Rejected by the Colombian Parliament. What happens between the treaties rejection and the construction of the canal? 1904 Canal construction begins Philippe-Jean BunauVarilla Copyright Bruce Lesh “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Written in protest of the presence of United States Navy and Marines in Panama at the outset of the Panamanian Revolution. Marroquin supported the Hay-Herran Treaty but felt mistreated by the United States after the revolution as worried that the loss of Panama might lead to his loss of power in Columbia. Source B From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) “The Government of the United States is treating Colombia in a manner that seems dishonorable to all the people of that country. American Secretary of State Hay has astonished the world by finding a right to exclude the troops of Colombia from the Isthmus of Panama. The United States violated international law by recognizing the independence of Panama only days after the revolution and before the nation of Colombia had a chance to put down the insurrection. Colombia did not recognize the southern states which seceded during the American Civil War- why should the United States recognize the seceding states of Panama? How are you to escape the condemnation of history? Never has any nation dealt with a weak one in a way that seemed dishonorable to any considerable part of its own people but that history has affirmed the judgment of the protesting minority.” Copyright Bruce Lesh Source Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source B: From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. Impact of the subtext and context Information Provided Support/Challenge Copyright Bruce Lesh “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal The interview was given to an investigative journalist 37 years after the events. BunauVarilla was almost 90 years old at the time of the interview. The story of the interview was then retold in American Heritage Magazine. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. “It was his [Buna-Varillia’s] memories that interested me that winter in Paris. A cable from CBS in New York requested me to find out if the Colonel was still alive and if so, to have him make a five-minute broadcast on the Robert Ripley “Believe It or Not” radio program about his role in the Panama Canal… [Buana-Varilla told me that] First he had to be sure that if the revolt came off successfully, the United States would give her protection to the new nation…as I sat one day in the old Colonel’s apartment, he told this story, as closely as my memory retains it: I called [visited] on Mr. Roosevelt [at the White House] and asked him point blank if, when the revolt broke out, an American war ship would be sent to Panama to “protect American lives and interests.” The President just looked at me; he said nothing. Of course, a President of the United States could not give such a commitment, especially to a foreigner and private citizen like me. But his look was enough for me. I took the gamble. “He is a very able fellow,” Roosevelt later wrote about the encounter, “and it was his business to find out what he thought our Government would do. I have no doubts that he was able to make a very accurate guess, and to advise his people accordingly. In fact, he would have been a very dull man if he had been unable to make such a guess.” Not that a single man can produce a rebellion; there were plenty of disgruntled Panamanians ready to help, and various meetings with their representatives took place at Bunau-Varilla’s Waldorf-Astoria suite. They wanted six million dollars, chiefly to pay their ragged guerrilla force. BunauVarilla got the price down, he said, to 1100,000, and paid it out of his own pocket. Next he busied himself drafting a Panamanian declaration of independence and a constitution. He even bought silk at Macy’s for a Panamanian flag, which he designed and which his wife and a family friend stitched together at a Westchester County estate.” Copyright Bruce Lesh Source Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source B: From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. Impact of the subtext and context Information Provided Support/Challenge Copyright Bruce Lesh Source Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source B: From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. Impact of the subtext and context Information Provided Support/Challenge Copyright Bruce Lesh “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal The New York Times was developed to counter the yellow journalism of other New York newspapers. The paper was not supportive of American imperial efforts. The cartoon appeared in the immediate aftermath of the Panamanian Revolution and the American acquisition of the land upon which the canal was built. President Roosevelt Panama Revolution Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Precedent: an earlier event or action that is regarded as an example or guide to be considered in subsequent similar Copyright Bruce Lesh Treaty with the United States “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Published in the New York Times investigative story on the events in Panama. The cartoon was a muckraking attempt to investigate the president. The cartoon appeared in the immediate aftermath of the Panamanian Revolution and the American acquisition of the land upon which the canal was built. Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Copyright Bruce Lesh Source Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source B: From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. Impact of the subtext and context Information Provided Support/Challenge Copyright Bruce Lesh “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal This was a private letter (not intended for public consumption) between the former President and his former Secretary of State. The letter was written in 1915, after Roosevelt failed in his bid to win the presidency as a Progressive and is the former President’s reflections on the events leading up to the Panamanian Revolution. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 To talk of Columbia as a responsible power to be dealt with as we would deal with Holland or Belgium or Switzerland or Denmark is a mere absurdity. The analogy is with a group of Sicilian or Calabrian bandits…You could no more make an agreement with the Columbian rulers than you could nail currant jelly to a wall…I did my best to get them to act straight. Then I determined that I would do what ought to be done without regard to them. The people of Panama were a unit in desiring the canal and wishing to overthrow the rule of Columbia. If they had not revolted, I should have recommended to Congress to take possession of the Isthmus by force of arms; and, as you will see, I had actually written the first draft of my message to this effect. When they [Columbians living in Panama] revolted, I promptly used the Navy to prevent bandits, who had tried to hold us up, from spending months of futile bloodshed in conquering or endeavoring to conquer the isthmus, to the lasting damage of the Isthmus, of us, and of the world. I did not consult [Secretary of State] Hay or [Secretary of War] Root, or anyone else as to what I did, because a council of war does not fight; and I intended to do the job once and for all. Copyright Bruce Lesh Source Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source B: From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. Impact of the subtext and context Information Provided Support/Challenge Copyright Bruce Lesh “I took Panama”: President Theodore Roosevelt and the Panama Canal Written after Roosevelt’s death by the former French engineer and first Panamanian Minister to America. Written as a personal narrative of what happened in Panama, and was the second book written by Bunau-Varilla about the Panamanian Revolution. Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. From the Books: Introduction: [Readers] will see that the Panama Revolution of November, 1903, was nothing but the legitimate expression of the right of a nation to dispose of herself. They will be convinced that the United States Government had no more hand in it than had the French Government… In spite of the concealed, disguised, or open accusations against the Roosevelt policy, nothing has been brought for sixteen years to support the slightest shadow of a proof of complicity between the American Government and the Panama revolutionists. …The reader will now also completely understand that the President of the United States was absolutely free from secret connivance with the revolutionists. He will understand, now, Mr. Roosevelt's meaning when he said: "I took Panama." The dissemination of the truth about the Panama Revolution will also help to eliminate the pressure exercised on the conscience of some people by the idea that Colombia was wronged. They will see that since the Revolutionary War of the English colonies of America, there never was a clearer case of the right of a nation to dispose of itself. Colombia has, not and never had, the slightest title to receive an indemnity for the separation of Panama. From a Later Chapter: “In preparing the revolution I avoided anything that could be interpreted as a connivance [done secretly] between Washington and the insurgents. If President Roosevelt went with the high speed which was indispensable for final success, after the revolution became a fact, it was because I had carefully respected his independence. People may smile while speaking of a Roosevelt "staged revolution"; their smile will simply expose their own gullibility in believing the tales of imaginative wickedness. I wish to caution the reader in advance against the impression that the American Government had a hand in the Panama Revolution, because such a statement is absolutely fabricated—and devoid of any foundation in fact. Copyright Bruce Lesh Source Source A: “Panama or Bust” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source B: From a letter by Jose Marroquin, President of Colombia “The Rights of Colombia- A Protest and Appeal” (November 28, 1903) Source C: “The Man Behind the Egg,” The New York Times, 1903, artist unknown. Source D: Private letter from President Roosevelt to his former Secretary of State, John Hay July 2, 1915 Source E: Philippe Bunau-Varilla. The Great Adventure of Panama: Wherein Are Exposed Its Relation to the Great War and also the Luminous Traces of The German Conspiracies Against France and the United States. Doubleday, Page & Company: Garden City, New York, 1920. Source F: Eric Sevaried, “The Man Who Invented Panama – Interview of Bunau-Varilla.” American Heritage Magazine, August 1963, Vol. 14, No. 5. Impact of the subtext and context Information Provided Support/Challenge Copyright Bruce Lesh