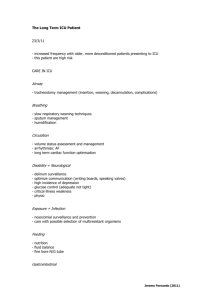

Long-Term Care of Patients

advertisement

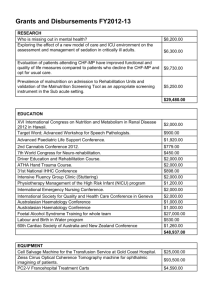

Long-Term Care of Patients After Discharge from the Intensive Care Unit Christina Jones and Richard D Griffiths Intensive Care Research Group, ICU Whiston Hospital & School of Clinical Science, University of Liverpool, UK Traditionally, following discharge from the intensive care unit (ICU), a patient’s care was placed in the hands of the original admitting team. However, in recent years, it has become clear that patients encounter problems, both in the acute setting and once they have returned home, that may not be addressed by this method. Sepsis patients account for a significant proportion of individuals admitted to the ICU and therefore represent a large population that require post-ICU assessment and care. The recognition of deterioration in patients recovering from critical illness once they have moved to general wards may be enhanced by following patients through an outreach process in the first few days. Simple interventions such as training ward staff in the care of tracheostomies may be life saving. In the longer term, many ICU patients report a core of physical and psychological problems, some of which respond to structured rehabilitation. Early recognition of severe psychological distress such as post-traumatic stress disorder allows the prompt referral of these patients for appropriate help before the condition becomes chronic. Adv Sepsis 2006;5(3):88–93. Severe sepsis is a leading cause of admission to intensive care units (ICUs), with studies in the US and Europe demonstrating that it accounts for up to 25% of patients requiring ICU treatment [1–4]. Until recently, research into outcome following critical illness focused on the mortality rate after discharge from the ICU. Gradually, the focus has shifted to morbidity, with the intention of helping patients to rebuild their health. This article will examine some of the problems that are reported by recuperating patients, and suggest some methods for improving their recovery. Early post-ICU care Many patients can be discharged from the ICU to general wards without the risk of their condition deteriorating. However, certain groups of patients, such as those recovering from acute renal failure or discharged with a tracheostomy in situ, are at high risk of deterioration. Clear plans for further care, specifying requirements such as daily blood tests and maintenance of a strict fluid balance, may be passed on to ward staff by the ICU team, but not implemented. In addition, the care of tracheostomies may be poor because of a lack of practice by ward staff. Such skills need to be updated on a regular basis. As a consequence, in the UK, “outreach” teams from critical care departments have been established. Their role is not to take over patient care, but to ensure that non-ICU staff are able to recognize when a patient is becoming critically ill, to improve their skills in caring for specific patients, e.g. those with a tracheostomy, and to provide advice. On discharge of patients to the general wards, the aim of follow-up for the ICU should be to either prevent readmission to ICU or, if necessary, to ensure prompt readmission. Following the introduction of an ICU outreach service to one hospital, the rate of survival until discharge from hospital after leaving the ICU was improved by 6.8%, and readmission to critical care was decreased by 6.4% [5]. A retrospective study showed a 40% reduction in cardiac arrest rate, together with an ICU readmission rate within 48 h of discharge of <2%, following the introduction of an outreach team [6]. Specialist teams such as a tracheostomy service may also be of help. One study examined the introduction of such a service in a hospital without an on-site ear, nose, and throat facility [7]. It showed a reduction in discharges of patients with tracheostomy tubes from the ICU to the wards (p=0.006) and a reduction in tracheostomy-related complications on the wards (p=0.031) [7]. Recovery from critical illness Physical recovery For the majority of patients, physical recovery after discharge from the ICU is excellent. However, for some patients, particularly those aged >50 years and those who have required a long stay in the ICU, physical recovery from critical illness is prolonged, in some cases taking >1 year [8]. A vast loss of lean body mass, mainly skeletal muscle, can occur in the catabolic phase of critical illness. The loss may average 2% per day and can lead to profound muscle weakness [9]; the diaphragm and other skeletal muscle of the respiratory system are not protected from the muscle loss. Rebuilding of lost muscle occurs slowly and requires both physical activity and good nutrition. Weight loss can be significant; for example, a loss of 18% in body mass in adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients was observed in one study [10]. In another study, a 19–21% loss of body ass was seen in general ICU patients [11]. In addition, some patients may develop critical illness polyneuropathy (CIPN), which is characterized by axonal degeneration of motor nerves [12]. In severe muscle wasting following a prolonged septic illness, upper limb wasting can be so profound that selffeeding is simply too tiring for the patient to achieve adequate oral intake. Patients require help with feeding in this situation. Even 2 months after discharge, longer-stay patients may report difficulty climbing the stairs [13]. Similarly, walking outdoors is difficult for these patients and they tend to use a wheelchair. While some of the physical difficulties are due to poor muscle strength and the ease with which patients become fatigued [10], weakness of the postural muscle also results in patients having difficulty in getting up if they fall. Consequently, they may feel insecure and frightened of falling. In addition, patients report joint pain, most commonly shoulder pain, which may compromise their ability to care for themselves (see Table 1 for examples of physical complaints). Those patients who develop CIPN may take even longer to recover and need intensive rehabilitation to reduce residual disabilities [14,15]. Patients may also develop other, more minor, physical problems such as hair loss or bald patches where the head was in contact with the pillow. These problems have greater significance for the patient when they are not properly explained. Psychological issues during recovery Until recently, little was known about the psychological sequelae of critical illness. However, with the advent of followup questionnaires and outpatient clinics for ICU patients, it is clear that there can be profound long-term psychological and psychosocial effects. One questionnaire study of 655 patients found a high incidence of psychosocial dysfunction, particularly in younger individuals [16]. Other studies have shown significant levels of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [17–21]. Agoraphobia and panic attacks can also be precipitated (Table 2). Such problems can have a significant long-term impact on both patients’ and their family’s quality of life. Relatives of ICU patients are also at significant risk of developing PTSD, and there is a strong correlation between patients and their close family members with respect to the level of PTSD symptoms (Table 3) [22–24]. The development of PTSD in family members can credibly be attributed to the recall of their experience of the patient’s stay in ICU. However, patients’ recall of their time in ICU and the events prior to admission is likely to be poor [25]. A delusional memory of hallucinations, nightmares, or paranoid delusions recalled from the time in ICU may be the traumatic event that precipitates the development of PTSD. Where delusional memories are the only recall of ICU, with no factual recall, the risk of developing PTSD is very high [18]. Cognitive deficits following critical illness Cognitive problems, in the form of delirium, are common during critical illness. They are partly due to the severity of illness and the large cumulative doses of sedative and/or opiate drugs that patients receive. However, it is only recently that studies have begun to examine the longer-term effects of critical illness on cognitive function, and significant cognitive deficits that may have an impact on the ability of patients to care for themselves are now being reported [26]. At present, it is unclear whether cognitive deficits are permanent (due to neurological damage) or may recover with time. One recent study suggests that, although some patients improve with time, a significant number remain impaired and may have problems with tasks such as financial management and driving [27]. Interventions to aid physical and psychological recovery Rehabilitation While there is increasing evidence of physical and psychological problems during recovery from critical illness, little work has been carried out on formal rehabilitation. However, evidence from rehabilitation programs in other patient groups, with both acute and chronic illness, shows improvements in physical functioning and reduced psychological distress. For example, rehabilitation programs, which may consist of exercise training, coping strategies, and provision of information, are becoming widespread in non-hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). These programs have been shown to improve exercise tolerance, perception of breathlessness, and health related quality of life [28–30]. They now form part of the recommended treatment for patients with COPD, with even severe sufferers gaining some benefit [31]. Individuals suffering from severe respiratory impairment following an ICU admission due to a non-obstructive pulmonary disease, e.g. pneumonia or ARDS, may benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation, with similar improvements in exercise tolerance seen to those in COPD patients [32]. Successful rehabilitation of ICU patients requires a multimodal program that has both physical and psychological elements. Individualization is necessary, as patients do not follow a set chronological pathway but may require diagnosis of differing individual physical or psychological problems. The provision of a multimodal recovery manual program was shown to accelerate the physical recovery of general ICU patients in a randomized, controlled study, with blinded follow-up [33]. The program consisted of a 6-week, patient-directed rehabilitation manual that provided information on a wide range of topics, such as the possible physical (e.g. muscle wasting, weakness, hair loss, taste changes, and appetite loss) and psychosocial and psychological (e.g. panic attacks, anxiety, and depression) sequelae of critical illness. It emphasized the normality of these reactions after severe stress, and also that they are likely to settle with time. In addition, it gave general advice on topics such as anxiety and stress management, relaxation, regaining normal fitness levels, eating well, and sexual problems after major illness. The importance of stopping smoking after critical illness was highlighted, and advice on cessation provided. Finally, there was a comprehensive exercise program. An important principle of the design was that the educational program was patient centered, with patients being encouraged to take responsibility for their own health. A total of 126 patients were randomized to receive either the ICU recovery manual program or standard follow-up [33]. At 2 months after discharge from the ICU, physical recovery was faster in patients receiving the recovery manual than in the controls; this was still evident at 6-month follow-up (p=0.006). In addition, significantly more patients receiving the recovery manual were able to stop smoking compared with the control group (relative risk reduction 89%, 95% confidence interval 98–36%) [34]. This has considerable importance as it improves the chance of lung recovery. Psychological recovery was more complex. There was a trend to a lower rate of depression at 2 months after ICU discharge (12% vs. 25%), although this was not statistically significant (p=0.06) [33]. More importantly, there were no differences in levels of anxiety and PTSD-related symptoms between the groups at 6 months. Further analysis showed that those patients who could recall delusional memories from their time on ICU were significantly more anxious and had higher levels of PTSD-related symptoms than those who did not have these memories, regardless of whether or not they had received the rehabilitation program. Clearly, such patients need to be identified and referred for appropriate help. At present, in the UK, the provision of specialist ICU rehabilitation after hospital discharge is almost non-existent. Physiotherapists at 36 large UK hospitals were surveyed about rehabilitation of ICU patients [35]. Although all of those questioned provided some rehabilitation on the wards, 93% of respondents felt there was a need for follow-up services to identify problems and to ensure that patients achieved their full functional potential. A few hospitals were found to have a specific rehabilitation team for ICU patients. ICU diaries The patients’ lack of a concrete memory of events that occurred in the ICU can hinder their recovery, as they have little comprehension of the severity of their illness or the length of time it will take them to recover. The use of ICU diaries, a simple idea that originated in Sweden, has begun to spread. Recording an ICU stay in everyday language by staff and the patient’s family, accompanied by appropriate photographs, is well received by patients, and is reported to help them rebuild a memory of this episode [36,37]. The inclusion in the diary of a description of any periods of agitation, confusion, or possible hallucinations can help the patient to identify the point at which delusional memories may have occurred. An example of this is a patient who had an ICU memory of being in a fire and having to be rescued by a fireman. The memory was hindering her recovery, but upon reading the diary she found that she had been urgently moved from the ICU to theater. It became clear to her that this was the source of her delusional memory, and, when she suffered a flashback of the event, she would read her diary to combat it. The recording of such a diary could be seen as a simple therapy to reduce the psychological impact of such memories, and requires further research to examine its impact on PTSD symptoms. PTSD The symptoms of PTSD can be overwhelming, and failure to recognize and successfully treat the syndrome can have a significant effect on recovery. Although the incidence of PTSD amongst ICU patients varies with the mix of cases and may have been exaggerated in some studies, it has a major impact on quality of life. Two recent sets of treatment guidelines emphasize the need to screen individuals after a traumatic event and refer those with high levels of symptoms for further professional help [38,39]. Where symptoms remain mild, “watchful waiting” is appropriate, as many individuals find their own way of working through their traumatic experiences. Where PTSD symptom levels are very high, referral for further professional help is appropriate. The guidelines published by the UK National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence point out that individuals suffering from PTSD should routinely be provided with information on common reactions to traumatic events, including the symptoms of PTSD, its course, and treatment [39]. The screening of ICU patients for PTSD is important, as individuals may feel the need to avoid talking about their problems, which is itself a part of the disorder. To facilitate the recognition of PTSD there may be a role for the use of PTSD-screening tools, such as the Impact of Event Scale [40], to assess patients and their families. However, it is important that PTSD assessment is carried out by appropriately trained individuals and is comprehensive, including physical, psychological, and social measurements, and a risk assessment. Some individuals will be functioning satisfactorily despite relatively high levels of symptoms, and may feel that they can cope on their own. These individuals can be reassessed after 1 month. At present, only approximately one-third of ICUs in the UK provide follow-up in a dedicated clinic, and it is likely that patients may initially go to their family doctor for advice on PTSD. Education is required to ensure that clinicians who treat patients in the community are aware of PTSD symptoms and have a high index of suspicion when assessing post-ICU patients. The provision of counseling, psychotherapy, or psychology services specifically for post-ICU patients is sparse in the UK. The growth of counseling services for patients diagnosed with cancer has arisen from the recognition of the psychological impact of such a severe illness. Perhaps critical care providers need to think along similar lines because of the high risk of psychological effects for both patients and families following an illness in ICU. The inter-relationship between high levels of PTSD-related symptoms in patients and their families points to the need for family therapy and support groups. Additionally, there may be a need for marital and sexual counseling in circumstances where both partners are suffering from PTSD. Conclusion The burden of a critical illness on both patients and their family can be extreme. In addition to physical problems, cognitive and psychological dysfunction have a significant impact, which is only now being recognized. Care must continue long after discharge from the ICU and a prolonged recovery time can be expected. Some recommendations for care after discharge are shown in Table 4. The pathway of care offered to patients must improve if their full potential for recovery is to be realized. ICU physicians, nurses, and other professionals have important roles to play in the management of patients after discharge. Disclosures The authors have no relevant financial interests to disclose. References 1. Angus DC, Wax RS. Epidemiology of sepsis: an update. Crit Care Med 2001;29:S109–16. 2. Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J et al. Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:1303–10. 3. Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med 2006;34:344–53. 4. Harrison DA, Welch CA, Eddleston JM. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, 1996 to 2004: secondary analysis of a high quality clinical database, the ICNARC Case Mix Programme Database. Crit Care 2006;10:R42. 5. Ball C, Kirkby M, Williams S. Effect of the critical care outreach team on patient survival to discharge from hospital and readmission to critical care: non-randomised population based study. BMJ 2003;327:1014. 6. Wilton P, Carbery C, Farrimond J et al. Impact of critical care outreach on cardiac arrest rates and readmission rates in an adult cardiothoracic centre. Crit Care 2005;9:P268. 7. Norwood MG, Spiers P, Bailiss J et al. Evaluation of the role of a specialist tracheostomy service. From critical care to outreach and beyond. Postgrad Med J 2004;80:478–80. 8. Jones C, Palmer TE, Griffiths RD. Recovery from intensive care continues for up to one year. Intensive Care Med 1992;18:S136. 9. Griffiths RD. Nutrition after critical illness. In: Griffiths RD, Jones C, editors. Intensive Care Aftercare. Oxford: Butterworth & Heinemann, 2002:48–52. 10. Herridge MS, Cheung AM, Tansey CM et al. One-year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2003;348:683–93. 11. Kvale R, Ulvik A, Flaatten H. Follow-up after intensive care: a single center study Intensive Care Med 2003;29:2149–56. 12. Kennedy DD, Coakley J, Griffiths RD. Neuromuscular problems and physical weakness. In: Griffiths RD, Jones C, editors. Intensive Care Aftercare. Oxford: Butterworth & Heinemann, 2002:7–18. 13. Jones C, Griffiths RD. Identifying post intensive care patients who may need physical rehabilitation. Clin Intensive Care 2000;11:35–8. 14. Zifko UA. Long-term outcome of critical illness polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve Suppl 2000;9:S49–52. 15. van der Schaaf M, Beelen A, de Vos R. Functional outcome in patients with critical illness polyneuropathy. Disabil Rehabil 2004;26:1189–97. 16. Tian ZM, Miranda DR. Quality of life after intensive care with the sickness impact profile. Intensive Care Med 1995;21:422–8. 17. Jones C, Humphris GM, Griffiths RD. Psychological morbidity following critical illness – the rationale for care after intensive care. Clin Intensive Care 1998;9:199–205. 18. Schelling G, Stoll C, Meier M et al. Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of adult respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med 1998;26:651–9. 19. Scragg P, Jones A, Fauvel N. Psychological problems following ICU treatment. Anaesthesia 2001;56:9–14. 20. Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G et al. Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med 2001;29:573–80. 21. Cuthbertson BH, Hull A, Strachan M et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder after critical illness requiring general intensive care. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:450–5. 22. Stukas AA, Dew MA, Switzer GE et al. PTSD in heart transplant recipients and their primary family caregivers. Psychosomatics 1999;40:212–21. 23. Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD et al. Post traumatic stress disorder-related symptoms in relatives of patients following intensive care. Intensive Care Med 2004;30:456–60. 24. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:987–94. 25. Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G. Disturbed memory and amnesia related to Intensive Care. Memory 2000;8:79–94. 26. Jackson JC, Hart RP, Gordon SM et al. Six-month neuropsychological outcome from medical intensive care unit patients. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1226–34. 27. Sukantarat KT, Burgess PW, Williamson RC et al. Prolonged cognitive dysfunction in survivors of critical illness. Anaesthesia 2005;60:847–53. 28. Ries AL, Kaplan RM, Limberg TM et al. Effects of pulmonary rehabilitation on physiological and psychosocial outcomes in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med 1992;122:823–32. 29. Carrieri-Kohlman V, Douglas MK, Gormley JM et al. Desensitization and guided mastery: treatment approaches for the management of dyspnea. Heart Lung 1993;22:226–34. 30. Goldstein RS, Gort EH, Stubbing D et al. Randomised controlled trial of respiratory rehabilitation. Lancet 1994;344:1394–7. 31. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Management of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. Clinical Guideline 12. London: NICE, 2004. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG012NICEguideline 32. Novitch RS, Thomas HM. Rehabilitation of patients with chronic ventilatory limitation from nonobstructive lung diseases. In: Principles and Practice of Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Casaburi R, Petty TL, editors. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders, 1993:416–23. 33. Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD et al. Rehabilitation after critical illness: a randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care Med 2003;31:2456–61. 34. Jones C, Griffiths RD, Skirrow P et al. Smoking cessation through comprehensive critical care. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:1547–9. 35. Lewis M. Intensive care unit rehabilitation within the United Kingdom: review Physiotherapy 2003;89:531–8. 36. Bergbom I, Svensson C, Berggren E et al. Patients’ and relatives’ opinions and feelings about diaries kept by nurses in an intensive care unit: pilot study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 1999;15:185–91. 37. Bäckman CG, Walther SM. Use of a personal diary written on the ICU during critical illness. Intensive Care Med 2001;27:426–9. 38. Foa EB, Davidson JR, Frances A. The expert consensus guideline series – treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 1999;60:1–75. 39. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): The Management of PTSD in Adults and Children in Primary and Secondary Care. Clinical Guideline 26. London: NICE, 2005. Available at: www.nice.org.uk/CG026NICEguideline 40. Witteveen AB, Bramsen I, Hovens JE et al. Utility of the impact of event scale in screening for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychol Rep 2005;97:297–308. 41. Jones C, Griffiths RD, Macmillan RR et al. Psychological problems after intensive care. Brit J Intensive Care 1994;2:46–53. 42. Koshy G, Wilkinson A, Harmsworth A et al. Intensive care unit follow-up program at a district general hospital. Intensive Care Med 1997;23:S160. 43. Nelson BJ, Weinert CR, Bury CL et al. Intensive care unit drug use and subsequent quality of life in acute lung injury patients Crit Care Med 2000;28:3626–30. 44. Schnyder U, Moergeli H, Klaghofer R et al. Incidence and prediction of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in severely injured accident victims. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:594–9. 45. Dew MA, Kormos RL, DiMartini AF et al. Prevalence and risk of depression and anxietyrelated disorders during the first three years after heart transplantation. Psychosomatics 2001;42:300–13. 46. Schelling G, Richter M, Roozendaal B et al. Exposure to high stress in the intensive care unit may have negative effects on health-related quality-of-life outcomes after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1971–80. 47. Köllner V, Einsle F, Schade I et al. The influence of anxiety, depression and post traumatic stress disorder on quality of life after thoracic organ transplantation. Z Psychosom Med Psychother 2003;49:262–74. 48. Gamper G, Willeit M, Sterz F et al. Life after death: posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of cardiac arrest – prevalence, associated factors and the influence of sedation and analgesia. Crit Care Med 2004;32:379–83. 49. Jones C, Capuzzo M, Flaatten H et al. Intensive care and patient factors related to posttraumatic stress disorder. Intensive Care Med 2005;31:S176. 50. Hopkins RO, Weaver LK, Collingridge D et al. Two-year cognitive, emotional, and qualityoflife outcomes in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:340–7. 51. Jones C, Griffiths RD. Social support and anxiety levels in relatives of critically ill patients. Br J Intensive Care 1995;5:44–7. 52. Dew MA, Myaskovsky L, Dimartini AF et al. Onset, timing and risk for depression and anxiety in family caregivers to heart transplant recipients Psychol Med 2004;34:1065–82.