Sheet 13.1 Plate tectonics - Science for the NZ Curriculum

advertisement

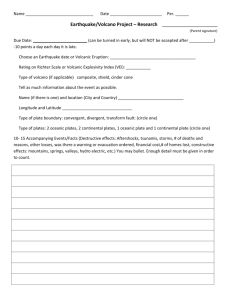

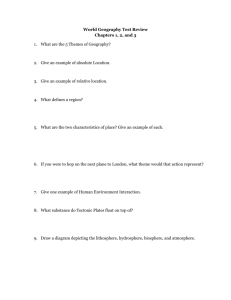

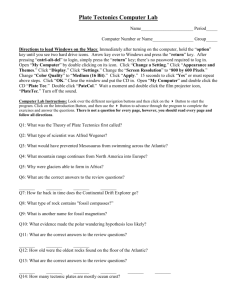

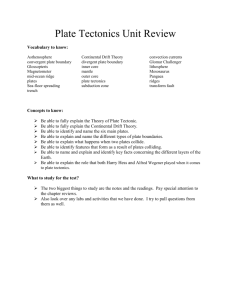

Sheet 13.1 Revision Plate tectonics 1 Sheet 13.1 Revision Plate tectonics Tectonic plates The crust of the Earth is divided into tectonic plates. The plates are less dense than the mantle (due to containing more silicon and aluminium) and float on it. On the surface some plates are spreading apart, some are colliding and some are stationary. The edges of the plates are called plate boundaries. Figure 4.3: Earth’s tectonic plates Continents A continent is a large land mass, often on its own tectonic plate. The land part of the tectonic plate is less dense and floats high enough to be above sea level. However, the edge of a continent may be below sea level. Plate boundaries Some tectonic plates are moving, driven by convection currents in the mantle below them. The edges of the plates, where they meet, are called plate boundaries. At a divergent plate boundary two plates are moving apart, causing a crack in the crust. Magma splits the diverging plate, oozes through the crack from the mantle and then hardens. This becomes a series of long mid-oceanic ridges and underwater volcanoes. This type of boundary usually occurs where the tectonic plates are thin, in the ocean. The thinner part of a tectonic plate is called an oceanic plate (the thicker part is called a continental plate). The oceanic plate is denser than the continental plate, so it is below sea level. When Science for the New Zealand Curriculum Years 9 and 10 © Donald Reid, Catherine J. Bradley, Des Duthie, Catherine Low, Matthew McLeod, Colin Price 2010 Published by Cambridge University Press www.nzscience.co.nz www.cambridge.edu.au Sheet 13.1 Revision Plate tectonics 2 covered in sediment it forms the floor of the oceans. New ocean floor is slowly being formed at these boundaries and spreads outwards, a process called sea-floor spreading. Occasionally the mid-oceanic ridges at divergent plate boundaries protrude above the oceans, forming volcanic islands. The fiery, red, fast-flowing basalt lava flows of Hawaii and Iceland are examples. Figure 4.4: Divergent plate boundary showing sea-floor spreading At a transform fault boundary, two plates alongside each other are passing, which may cause earthquakes as they rub roughly together. At a collision plate boundary, two thick continental plates are colliding with one another. Parts of the plates are forced up, resulting in large fold mountains. An example of this is the Himalayan mountain range which has over 100 mountains higher than 7200 m. These peaks are the result of a 50 million year long collision between the Indian and Eurasian plates. Because these plates have not stopped moving, earthquakes in this region are fairly common. Figure 4.5: Transform fault boundary Science for the New Zealand Curriculum Years 9 and 10 © Donald Reid, Catherine J. Bradley, Des Duthie, Catherine Low, Matthew McLeod, Colin Price 2010 Published by Cambridge University Press www.nzscience.co.nz www.cambridge.edu.au Sheet 13.1 Revision Plate tectonics Figure 4.6: Collision plate boundary At a subduction plate boundary, (see next page) one plate is diving below the other. In most cases, a thinner oceanic plate is forced underneath a thicker, less dense continental plate. As the oceanic plate gets pushed down towards the hot mantle it melts, becoming magma again. However, the magma will be a mixture of continental crust (rich in silicon and aluminium), oceanic crust (basalt) and water. This mixture creates a superheated fluid that is under great pressure and rises to the surface to produce explosive, unpredictable volcanoes along the subduction zone. See page 63 for the evidence for plate tectonics. oceanic plate Thinner, more dense part of a tectonic plate continental plate Thicker, less dense part of a tectonic plate sea-floor spreading The formation of new oceanic plates at a divergent plate boundary transform fault boundary Where two tectonic plates are passing alongside each other collision plate boundary Where two tectonic plates are colliding with one another subduction plate boundary Where one tectonic plate is diving below another Science for the New Zealand Curriculum Years 9 and 10 © Donald Reid, Catherine J. Bradley, Des Duthie, Catherine Low, Matthew McLeod, Colin Price 2010 Published by Cambridge University Press www.nzscience.co.nz www.cambridge.edu.au 3