Advances in Appreciative Inquiry as an Organization Development

advertisement

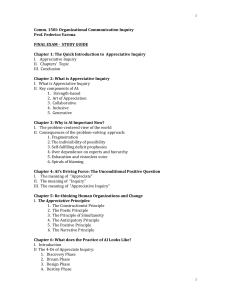

Advances in Appreciative Inquiry as an Organization Development Intervention (Published in the Organization Development Journal, Fall 1995 Vol.13, No.3, pp.14-22) Gervase R. Bushe Ph.D. Organization Development Faculty of Business Administration Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC, Canada V5A 1S6 (604)291-4104 email: bushe@sfu.ca Since Cooperrider & Srivastva's (1987) original article on appreciative inquiry there has been a lot of excitement and experimentation with this new form of action research. The technology of appreciative inquiry as a social research method and as an organization development (OD) intervention are evolving differently. Here I will mainly focus on it as an OD intervention. Currently there is no universally accepted method for doing an appreciative inquiry and it is premature to offer a "recipe" for how to do it. There is, however, a fairly well accepted set of parameters for distinguishing between what is and is not a legitimate appreciative inquiry. In this paper I will describe the basics of this technique and report on some innovations I and colleagues have experimented with to extend the appreciative approach. First, however, an introduction to the theory behind the technique. What is Appreciative Inquiry? Appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987), a theory of organizing and method for changing social systems, is one of the more significant innovations in action research in the past decade. Those who created action research in the 1950s were concerned with creating a research method that would lead to practical results as well as the development of new social theory. It was hoped that action research would be an important tool in social change. A key emphasis of action researchers has been on involving their "subjects" as co-researchers. Action research was and still is a cornerstone of organization development practice. While always controversial as a scientific method of inquiry, action research has recently come under criticism as a method of organizational change and as a process for developing new theory. In their seminal paper Cooperrider & Srivastva criticize the lack of useful theory generated by traditional action research studies and contend that both the method of action research and implicit theory of social organization are to blame. The problem is that most action research projects use logical positivistic assumptions (Sussman & Evered, 1978) ,which treats social and psychological reality as something fundamentally stable, enduring, and "out there". Appreciative inquiry, however, is a product of the socio-rationalist paradigm (Gergen, 1982, 1990) which treats social and psychological reality as a product of the moment, open to continuous reconstruction. Cooperrider and Srivastva argue that there is nothing inherently real about any particular social form, no transcultural, everlasting, valid principles of social organization to be uncovered. While logical positivism assumes that social phenomena are sufficiently enduring, stable and replicable to allow for generalizations, socio-rationalism contends that social order is fundamentally unstable. "Social phenomena are guided by cognitive heuristics, limited only by the human imagination: the social order is a subject matter capable of infinite variation through the linkage of ideas and action". (Cooperrider and Srivastva, 1987, p.139). Socio-rationalists argue that the theories we hold, our beliefs about social systems, have a powerful effect on the nature of social "reality". Not only do we see what we believe, but the very act of believing it creates it. From this point of view, the creation of new and evocative theories of groups, organizations, and societies, are a powerful way to aid in their change and development. Like most post-modernists, Cooperrider & Srivastva argue that logical positivistic assumptions trap us in a rear-view world and methods based on these assumptions tend to (re)create the social realities they purport to be studying. Further, they argue that action researchers tend to assume that their purpose is to solve a problem. Groups and organizationsare treated not only as if they have problems, but as if they are problems to be "solved". Cooperrider and Srivastva contend that this "problem-oriented" view of organizing and inquiry reduces the possibility of generating new theory, and new images of social reality, that might help us transcend current social forms. What if, instead of seeing organizations as problems to be solved, we saw them as miracles to be appreciated? How would our methods of inquiry and our theories of organizing be different? Appreciative inquiry "...refers to both a search for knowledge and a theory of intentional collective action which are designed to help evolve the normative vision and will of a group, organization, or society as a whole" (Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987, p.159). Cooperrider makes the theory of change embedded in appreciative inquiry explicit in a later paper on the affirmative basis of organizing (Cooperrider, 1990). In this paper Cooperrider proffers the "heliotropic hypothesis" - that social forms evolve toward the "light"; that is, toward images that are affirming and life giving. In essence his argument is that all groups, organizations, communities or societies have images of themselves that underlay self-organizing processes and that social systems have a natural tendency to evolve toward the most positive images held by their members. Conscious evolution of positive imagery, therefore, is a viable option for changing the social system as a whole. One of the ironies Cooperrider helps us to see is that the greatest obstacle to the wellbeing of an ailing group is the affirmative projection that currently guides the group. To affirm means to 'hold firm' and it "...is precisely the strength of affirmation, the degree of belief or faith invested, that allows the image to carry out its heliotropic task" (Cooperrider, 1990, p.120). When groups find that attempts to fix problems create more problems, or the same problems never go away, it is a clear signal of the inadequacy of the group's current affirmative projection. Groups, therefore, do not need to be fixed; they need to be affirmed and "...every new affirmative projection of the future is a consequence of an appreciative understanding of the past or present" (p.120). Appreciative inquiry, as a method of changing social systems, is an attempt to generate a collective image of a new and better future by exploring the best of what is and has been. These new images, or "theories", create a pull effect that generates evolution in social forms. The four principles Cooperrider and Srivastva (1987, p.160) articulate for an action research that can create new and better images are that research should begin with appreciation, should be applicable, should be provocative, and should be collaborative. The basic process of appreciative inquiry is to begin with a grounded observation of the "best of what is", then through vision and logic collaboratively articulate "what might be", ensuring the consent of those in the system to "what should be" and collectively experimenting with "what can be" . One significant published research study that used an appreciative inquiry methodology looked at the processes of organizing that are used by international non-governmental organizations (Johnson & Cooperrider, 1991). Appreciative Inquiry as a Method of Change An appreciative inquiry intervention can be thought of as consisting of these three parts: Discovering the best of.... Appreciative interventions begin with a search for the best examples of organizing and organization within the experience of organizational members. Understanding what creates the best of.... The inquiry seeks to create insight into the forces that lead to superior performance, as defined by organizational members. What is it about the people, the organization, and the context that creates peak experiences at work? Amplifying the people and processes who best exemplify the best of.... Through the process of the inquiry itself, the elements that contribute to superior performance are reinforced and amplified. The emphasis in my approach is on designing inquiry methods that amplify the values the system is seeking to actualize during the all phases of the inquiry process. I believe this is one key feature that distinguishes appreciative inquiry from other interventions. How to actually do that in practice is not so easy but as the pace of environmental change accelerates, we must find more rapid change processes for organizational renewal. The great promise of appreciative inquiry is that it will generate self-sustaining momentum within an organization toward actualizing the values that lead to superior performance. The original form of appreciative inquiry developed by David Cooperrider involved a bottom-up interview process where almost all organizational members were interviewed to uncover the "life-giving forces" in the organization. People were asked to recall times they felt "most alive, most vital, most energized at work" and were then questioned about those incidents. The interview data were then treated much the same as any qualitative data set; through content analysis the consultants looked for what people in the organization valued and what conditions led to superior performance. This analysis was fed back into a large planning group which was charged with developing "provocative propositions". Provocative propositions were statements of organizational aspiration and intent, based on the analysis of the organization at it's very best. These propositions were then validated by organizational members along two dimensions: 1) how much does this statement capture our values? and 2) how much are we like this? Nothing more was done with the data, analysis or propositions. John Carter of the Gestalt Institute of Cleveland, one of the early implementors of this approach, counsels against using the propositions as a set of standards or goals to then begin problem-solving around (Carter, 1989). Using the gestalt therapy notion of figure-ground, John argues that most inquiry methods make something figural, focusing attention. Appreciative inquiry, he claims, creates ground. By coming to agreement on a set of provocative propositions, people have a compelling vision of the organization at its best and this in itself motivates new behaviors. People will take initiative and act differently without an action plan because the provocative propositions align organizational vision with employee's internal sense of what is important. As a planned change technique, this approach lacked focus and didn't do as good a job of amplification as many of us would like. I continue to experiment with new techniques for generating discovery, understanding, and amplification. Here is a brief rundown on my current thinking. A) Discovering The initial appreciative inquiries attempted to study organizations as a whole. More recent interventions have begun to limit themselves to a few issues. This appears to make the process more manageable and understandable to others. Now, unless we are trying to help a company develop a future vision for the entire organization, appreciative inquiries focus on strategic human resource issues like empowerment, teamwork, leadership, customer service. Appreciative inquiry may have applications for other, non-HR issues but I don't know of anyone who has tried it (e.g., how to best organize an information system). One of the more interesting recent applications has been with gender issues in organizations. Marjorie Schiller of Quincy, Massachusetts has been working with corporations that found that traditional approaches to dealing with sexual harassment in the workplace (e.g., hire a harassment coordinator, gather survey data, do a lot of training) only resulted in more reported sexual harassment! Using an appreciative inquiry approach, teams of men and women are studying what co-gender work experiences are like at their very best and this seems to be having remarkable results. After a couple of failures I learned that doing an "appreciative interview" is not as easy as it looks. Simply talking about one's "peak" experience can easily degenerate into social banter and cliché-ridden interaction. The hallmark of successful appreciative interviews seems to be that the interviewee has at least one new insight into what made it a peak experience. I have noticed a bundle of behaviours that seem to distinguish those who are good and poor at appreciative interviewing (Bushe 1997). The key seems to be suspending one's own assumptions and not being content with superficial explanations given by others; to question the obvious and to do this in more of a conversational, selfdisclosing kind of way than is normally taught in interviewing courses. There seem to be real limits to who can do this well and I have not been able to train people quickly (1 day) to be able to attend to others appreciatively. It appears that one of the early assumptions, that we could teach organizational members to run the data collection process by themselves, does not work as well as we'd hoped. People who have the basic ability to listen to others "generously", however, can be taught appreciative inquiry in about a day and a half. I have found the best results from teaming insiders with outsiders and doing paired interviews. David Cooperrider has noticed that using younger insiders to interview organizational elders results in a very special energy and the quality of images and data seems better. I've come to the conclusion that getting the stories that people have about the topic is what is most important. Researchers and other linear thinkers have a tendency to want to generate abstract lists and propositional statements out of the interviews and this needs to be curtailed during the interview process or the same old lists and propositions get recycled. Fresh images and insight come from exploring the real stories people have about themselves and others at their best. We've also found that people love to be interviewed appreciatively. Recently a team I was leading completed a series of appreciative interviews about leadership with the senior executives of a major telecommunications company. As you can imagine, many were loath to give up any time in their busy schedules to be interviewed. We asked for an hour. Most interviews actually lasted two and a half hours, with the executives canceling their appointments and just wanting talk on and on. B) Understanding It has been necessary to find ways of making the data useful for group interpretation. Large data sets on organizational peak experiences required more time and effort than busy managers could afford. We've experimented with structuring the data collection and reporting to reduce the ambiguity of the data and make it easier for large groups to work with. The main innovation has been the inquiry matrix (Bushe & Pitman, 1991). Prior to data collection, senior managers decide what elements of organizing they want to amplify in their organization (e.g., teamwork, quality, leadership), and an organizational model that they feel best captures the major categories of organizing (e.g., technology, structure, rewards, etc.). A matrix is then created of elements by categories. For example, there would be a cell for teamwork & technology, teamwork & structure, quality & technology, quality & structure, and so on. The data collection effort focuses on each of the cells. More importantly, the matrix focuses the analysis of the data and the generation of provocative propositions. I have found that the quality of new understandings and insights created during an appreciative inquiry is strongly effected by the quality of stories and insights generated during the interviews. Unless new understandings arise during the initial appreciative interviews, later analyses may simply recreate the initial mental models people come to the analysis with. Without important new insights, the process loses energy fast and leads to cliched propositions. Appreciative inquiry really challenges those doing the analysis to leave their preconceptions behind and approach the data with "the eyes of a child". Write-ups of the interviews are very important. I've found that detailed recounts of the stories and most interesting quotes are what is needed and that these are best written in the first person. The output of appreciative interviews are a series of stories and quotes written in the language of those who told them. What is normally the "data analysis" stage of action research needs to be done totally differently in an appreciative inquiry. I no longer call it "analysis". I haven't found a great term for it yet but I've used 'proalysis' and 'synergalysis'. At this point in an appreciative inquiry I want to get as many people as possible reading the most important interviews and stories in order to stimulate their thinking about the appreciative topic. Then I try to orchestrate one or more meetings where organizational members and consultants try to go beyond what they were told by the interviewees to craft propositional statements about the appreciative topic that will capture people's energy and excitement. We're not trying to extract themes from the data or categorize responses and add them up. We're trying to generate new theory that will have high face value to members of the organization. What makes this legitimate research, I believe, is that we go back to those we interviewed with these propositions and ask them if we have captured the spirit, if not the letter, of the meaning of the interviews. If they say yes, then I believe we have generated new theory based on something more real than simply imagination and good intentions. C) Amplification I believe that as a social intervention device, the quality of the dialogue generated is much more important than the "validity" of the synergalysis of the data. Studying the best of what is creates excitement and energy and this is a key part of the amplification process. I and others have been trying to find ways to further amplify what is exciting and energizing for people and effective for their organizations. The number of people involved in all phases of the appreciative inquiry has obvious implications for this. I would like to experiment with getting very large numbers of people into something the size of a hockey arena to do consensual creation and validation of provocative propositions but to date have not found a client system willing to do this. Once a set of propositions have been developed, they can be "tested" through a survey in the organization. The survey can ask to what extent they believe the proposition to be an important component of the topic under study and to what extent they believe the organization exemplifies the proposition. Simply filling out such a survey can do a lot toward spreading the ideas throughout the organization. Then communicating the results of the survey showing the strength of consensus about the importance of each proposition gives organizational members license to do more of it in their everyday work.. One major innovation has been to create thematic feed-back documents that identify who is giving the "quote" and the context the quote was given in. Instead of lists of anonymous quotes to illustrate themes found in conventional feedback reports, people get to read what their fellow employees are saying about their best experiences. You can imagine how much more dialogue and energy this creates. Tom Pitman of Grand Rapids, Michigan and Geoff Hulin of Santa Cruz, California have experimented with video-taping the interviews and editing them into short, focused pieces on different themes. As a feedback device, videotape clips have proved to generate a great deal more energy and shared imagery than written reports. Again, the goal here is to create appreciative dialogues about the issues under study that result in new affirming images.. The opportunities here continue to increase as new applications that marry video and computer technologies proliferate. Where to next We may find that the notion of "appreciative process" (Bushe & Pitman, 1991) as a consulting and change strategy has a larger and more lasting impact than large scale appreciative inquiries. My personal consulting style has undergone a radical transformation in the past 6 years as I have struggled to adopt an appreciative stance in my work. Now I pay attention to what is working well, the qualities of leadership or group process that I want to see more of, and try to amplify them when I see them. This is in direct contrast to my training where I learned to see what was missing and point that out. In the past I focused on understanding the failures and pathologies of leadership and organization. I thought that awareness was the first step in development and so I felt it was my job as an OD consultant to make people aware of just how bad things really were. Now I am focusing on helping people become aware of how good things are, on the genius in themselves and others, on the knowledge and abilities they already have, on examples of the future in the present. From this stance I am finding that change happens more easily, people don't get as bogged down in uncertainty or despair and energy runs more freely. The appreciative lens has opened up a new vista for viewing and understanding the process of change in human systems. For example, I developed a form of appreciative inquiry for team building, experimentally tested it, and found it significantly improved a team's process and performance (Bushe & Coetzer, 1995). The method, as used in the experiments, goes as follows: First, group members are asked to recall the best team experience they have ever been a part of. Even for those who have had few experiences of working with others in groups, there is a 'best' experience. Each group member is asked, in turn, to describe the experience while the rest of the group is encouraged to be curious and engage in dialogue with the focal person. The facilitator encourages members to set aside their clichés and preconceptions, get firmly grounded in their memory of the actual experience, and fully explore what about themselves, the situation, the task, and others made this a "peak" experience. Once all members have exhausted their exploration, the facilitator asks the group, on the basis of what they have just discussed, to list and develop a consensus on the attributes of highly effective groups. The intervention concludes with the facilitator inviting members to publicly acknowledge anything they have seen others in the group do that has helped the group be more like any of the listed attributes This research has stimulated new group theory and new change theory. Graeme Coetzer, at Simon Fraser University, and I are working on a theory of "group image" that may offer insights into how groups function and dysfunction. I believe that the most important next steps for appreciative inquiry will be theoretical breakthroughs in understanding leadership, facilitation, and change processes in social systems. After this will come new techniques. REFERENCES Bushe, G.R. (1997) Attending to Others: Interviewing Appreciatively. Vancouver, BC: Discovery & Design Inc. Bushe, G.R. & Coetzer, G. (1995) Appreciative inquiry as a team development intervention: A controlled experiment. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 31:1, 1931. Bushe, G.R. & Pitman, T. (1991) "Appreciative process: A method for transformational change". OD Practitioner, September, 1-4. Carter, J. (1989) Talk given at the Social Innovations Global Management conference, Weatherhead School of Management, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland Ohio November 13-17. Cooperrider, D.L. (1990) Positive image, positive action: The affirmative basis of organizing. In S.Srivastva & D.L. Cooperrider (Eds.), Appreciative Management and Leadership (pp.91-125). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Cooperrider, D.L. & Srivastva, S. (1987) "Appreciative inquiry in organizational life". In R. Woodman & W. Pasmore (eds.) Research in Organizational Change and Development: Volume 1 (pp.129-169). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, Gergen, K. (1982) Toward Transformation in Social Knowledge. New York: SpringVerlag. Gergen, K. (1990) Affect and organization in postmodern society. In S. Srivastva & D.L. Cooperrider (eds.), Appreciative Management and Leadership (pp.153-174). San Francisco, Jossey-Bass. Johnson, P.C. & Cooperrider, D.L. (1991) Finding a path with heart: Global social change organizations and their challenge for the field of organization development. In R. Woodman & W.Pasmore (eds.) Research in Organizational Change and Development: Volume 5 (pp.223-284). Greenwich CT: JAI Press. Sussman, G.I & Evered, R.D. (1978) An assessment of the scientific merits of action research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 23, 582-603. Back to Appreciative Inquiry home page Go to GervaseBushe.ca