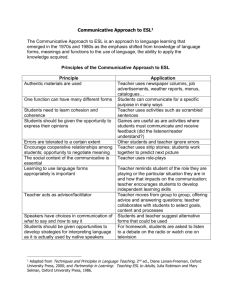

The Participation Theory of Communication

advertisement