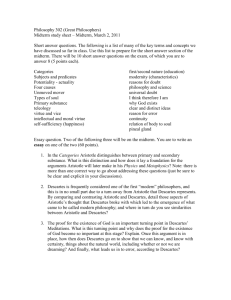

aquinas-and-baptistsgoodson

advertisement

Aquinas and Descartes on Transubstantiation: The Cartesian Imagination in Baptist Life By Jacob L. Goodson I. Introduction In a children’s sermon during a communion Sunday at my church, the teacher for that week rightly taught the children that there is a part of the Lord’s Supper that you cannot see. She, mistakenly in my view, went on to describe that mystery as being “in your hearts…remembering Jesus.” In this essay, I try to account for the importance of that mystery of the Lord’s Supper and how that part is not necessarily in our hearts – so to say – but rather in the elements. I think that Elizabeth Anscombe offers a better approach for a ‘childrens’s sermon’ on the Lord’s Supper than the person did at my church. Anscombe does not think that talk of transubstantiation will confuse children any more than any other description of the Eucharist. In fact, according to Anscombe, transubstantiation is best taught to children not in a ‘children’s sermon’ per se but while taking the Eucharist. She encourages us to describe to children what the elements are while waiting to take the elements with children. And the elements are, as Scripture says, the body and blood of Christ. So teach children that there is a part of the Lord’s Supper that you cannot see, and that part is that the bread and cup are the body and blood of Christ.1 It was unknowingly to both my father and I at the time, but he taught me to think of the Lord’s Supper in a similar way to that of Anscombe’s encouragement. My father For G. E. M. Anscombe’s wonderful account of teaching children the doctrine of transubstantiation, see her “On Transubstantiation,” in Ethics, Religion, and Politics: Collected Philosophical Papers, Volume III, (Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1981), 107-112. 1 is not a trained philosopher or theologian, and he would most likely affirm the Baptist understanding of the Lord’s Supper being a memorial supper that is ‘merely symbolic’. But at the age of six, I asked my father during the Lord’s Supper how I could get a cracker to eat and grape juice to drink. He told me that I had to walk to the front of the church and tell the pastor that I wanted to accept Christ as my Lord and Savior. So I did. When asked by the pastor and the children’s minister why I wanted to accept Christ, I said so that I could eat the cracker and drink the grape juice. I have thus always connected the Lord’s Supper with my conversion experience and thus also have linked accepting Christ “into my heart” with at least the desire for the elements. What my father taught me, then, was that it was not the cracker and grape juice that I wanted but rather it was Christ. And he is right. The Lord’s Supper, the Eucharist, is not about the cracker and the grape juice, the bread and the wine; it is about Christ, and whether or not we accept him. It is at this point that some philosophical questions come into play. Is Christ the bread and wine, or is he in the bread and wine? In Cartesian language, does he share the surface with the bread and wine? Or, given the Baptist language of ‘merely symbolic’ that I grew up hearing yet never thought sounded scriptural, is he there at all? Moreover, does the fact that one’s conversion and baptism are prerequisites for one’s participation in the Eucharist mean that Christ is always already in the individual believer? Or is Christ more present in the believer upon eating Christ at the Eucharist? In this essay, I argue that it is more consistent with Scripture to say that Christ is the bread and wine. Given that Christ says, “This is my body” and “This is my blood,” and given other statements of his found in the Gospel According to John, I think that to say Christ only shares the surface of the bread and wine is neither scripturally correct nor founded. It is not that the Cartesian account of transubstantiation is philosophically wrong, though it may be, but it is that it is not scriptural. Christ does not claim to share the surface of the bread and wine, and Christ does not claim that the bread and wine are ‘merely symbolic’. Christ claims that the bread is his body. Moreover, it seems that my testimony is an account of why it is the case that Christ is in an individual believer always already: in order to partake of the bread and wine, one has to accept Jesus as Lord and Savior. But that is not what Scripture says. In the Gospel According to John chapter 3, eternal life is received by believing in God: “For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, whosoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.” In the same Gospel, chapter 6 this time, eternal life is received by eating the flesh of Christ: “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up at the last day.” Furthermore, we are neither in Christ nor he in us until one eats his flesh and drinks his blood: “Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him.” I think that we have been so trained to read Scripture in a Cartesian way that we forget the fleshiness of the Johannine road to salvation. Salvation is found in the Eucharist because there is no salvation outside of the Church, and the Church is divinely made through the Eucharist.2 I think that my testimony is better understood in this way. I was drawn to God and God’s salvation for me in the church by the Eucharist because conversion is a Eucharistic claim. It is the desire for Christ to be in us and for us to be in Christ, and John reports Christ saying that such a desire is only fulfilled by eating his flesh and 2 See Henri de Lubac, Corpus Mysticum: The Eucharist and the Church in the Middle Ages, trans. Gemma Simmonds, (London: SCM Press, 2006). drinking his blood. Therefore, my testimony is but a concrete and explicit instance or occasion of what is recorded in the Gospel According to John: Jesus is only in us once we eat his flesh and drink his blood. Conversion, therefore, is better understood as wanting to eat and drink Christ so that he can be more present in us rather than being in us always already as a believer. Baptists need to account for this reading of John more than saying that it is to be read as ‘spiritual nourishment’ because the Lord’s Supper is not a necessity in Baptist life. In John 6, Christ teaches us that some practice of eating and drinking the body and blood of Christ is needed for eternal life and salvation. It seems, then, that I should be content if Baptists adopted the Cartesian theory of transubstantiation because it would be a recovery of the ‘real presence’ of Christ in the elements. But I think the problem with the Cartesian theory of transubstantiation is that it is a theory abstracted from Descartes’s own metaphysics, and it is not a doctrine grounded in Scripture.3 To accept Descartes’s theory of transubstantiation would be to accept the assumption that there is some kind of universal principle that is tradition-free that can prove clearly and distinctly the claims and convictions of Christians. I do not think that such a principle is available, and I do not want there to be one. The Christian tradition can be understood as the repetition of the interpretation of Scripture, and the logic of Scripture for such a repetition is Christ – which is what the 1963 Baptist Faith and Message claims when it says that Christ is the “criterion” by which Scripture is to be interpreted.4 If the Church’s one foundation really 3 See Jorge Secade, Cartesian Metaphysics: The Late Scholastic Origins of Modern Philosophy, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000): “Reluctantly but inevitably, Descartes…entered into Scholastic theological disputes about the Eucharist…” (1). See “Baptist Faith and Message of 1963,” in Baptist Confessions of Faith, ed. William L. Lumpkin, (Valley Forge: Judson Press, 1969), 393. 4 is Jesus Christ – as the hymn says it is, a hymn we sang in my church the same Sunday that the children’s sermon was on the mystery of the Lord’s Supper being that Jesus is in our hearts – then that is partly the case because the Church is made through the body and blood of Christ at the Eucharist. What Baptists need, then, is a scriptural account of the Eucharist. In this essay, I show how Baptists have an unlikely ally for such a scriptural account of the Eucharist. It is one of the doctors and patrons of the Roman Catholic Church: Saint Thomas Aquinas. His doctrine of transubstantiation is not merely an Aristotelian explanation for the Eucharist but is a scriptural account of the Eucharist that is also philosophically sophisticated enough to handle the questions raised by the biblical claim that the bread and wine is the body and blood of Christ. II. Cartesian Metaphysics Aquinas’s doctrine of transubstantiation describes the mystery that is the Eucharist. In order to describe this mystery, he employs the Aristotelian metaphysical categories of substance and accident. In his doctrine of transubstantiation, he develops how the substance of the bread and wine are converted into the substance of the body and blood of Christ while the accidents of the bread and wine remain. The bread and wine are the body and blood of Christ substantially. The bread and wine, then, are no longer bread and wine substantially but only accidentally. The bread and wine remain bread and wine accidentally because the bread and wine is what one tastes when partaking of the Eucharist. So the bread and wine remain accidentally according to our sense experience of the elements of the Eucharist. Explicitly following Aristotle and in the context of his doctrine of transubstantiation, Aquinas also says that the “proper object of substance” is the intellect. Knowledge of substance in the intellect, and not in the senses, is the only way to protect faith from deception. Faith “is not contrary to the senses,” Aquinas remarks, “but concerns things to which sense does not reach.”5 This formulation of faith works because, for Aquinas, there is no knowledge in the intellect that is not first in some way in the senses. In other words, for Aquinas’s doctrine of transubstantiation, the substance of the bread and wine is known intellectually as the body and blood of Christ while the accidents of the bread and wine are known through the senses as bread and wine. Descartes challenges this formulation. As Jorge Secada notes in his prologue to Cartesian Metaphysics, Descartes “saw himself as presenting a new philosophy, both natural and metaphysical, to take the place of Aristotle’s and St Thomas Aquinas’s.”6 Descartes’s approach to substance is determined by his intellectualist essentialism and is thus part of the larger context of Cartesian metaphysics. Cartesian metaphysics itself is an essentialism – which argues, against Scholastics like Aquinas, that essence is prior to existence. Descartes’s intellectualism challenges the kind of empiricism in Aquinas and defends the epistemological position “that the whole of human knowledge…is based on intellectual foundations.”7 In regards to substance, then, Descartes’s essentialism posits “that knowledge of the essence of a substance is prior to knowledge of its existence.”8 5 Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province, (Allen, Texas: Christian Classics, 1981), Pt. III, Q. 75, Art. 5; hereafter, citations will be given in the text in the following format: III.75.5. 6 Secada, Cartesian Metaphysics, 1. 7 Secada, Cartesian Metaphysics, 16. And his intellectualism renders knowledge of substance as only being accessible through the intellect and not through the senses. The essence of a substance is known only by the intellect, and it is known also prior to the existence of a substance.9 In other words, one has to know what the substance is before one knows that the substance is.10 III. Cartesian Theology In Descartes’s “Third Meditation” of his Meditations on First Philosophy, he meditates upon “the existence of God” and provides two definitions of God in his meditation. In this section, I argue that his second definition of God rids the practice of the Eucharist for understanding how God is within us. With Aquinas, I want to argue that there are degrees in which God is in us; 11 God is most present in us at the Eucharist because the elements of which we partake is God made flesh who is Christ, the second person of the trinitarian God. Descartes’s first definition of God is that God is “infinite substance,” but his second definition of God is the very being the idea of whom is within me, that is, the possessor of all the perfections which I cannot grasp, but can somehow reach in my thoughts, who is subject to no defects whatsoever.12 8 Secada, Cartesian Metaphysics, 8. For more on Cartesian substance, see Secada’s “Substance in Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy,” in The Blackwell Guide to Descartes’s Meditations, ed. by Stephen Gaukroger, (Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell, 2006). 9 In this sense, Descartes’s essentialism is completely contrary to Aquinas’s theology when he says that we cannot know what God is but only that God is in the first part of the Summa. 10 11 I owe this point to Paul Fiddes who provided the language of “degrees” for my initial claim here. Rene Descartes, “Third Meditation: The Existence of God,” in Meditations on First Philosophy, in The Philosophical Writings of Descartes: Volume II, ed. and trans. By John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, & Dugald Murdoch, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 35; hereafter, page numbers will be cited in the text preceded by the volume number as such: II.35. 12 God is not only an idea in Descartes but “the very being the idea of whom is within me” and can be reached “in my thoughts.” This second definition of God represents a shift in Cartesian theology – which can be summarized as God being both “infinite substance” and God being “the very being the idea of whom is within me.” Such a shift begs at least three questions. (1) How is it possible for God to be an infinite substance and to be “the very being the idea of whom is within me”? (2) Given that, for Descartes, knowledge of God is not analogical, 13 how do such possibly conflicting definitions of God work without reducing God to being only “the idea of [infinite substance]…within me”? And (3) if “the very being the idea of whom is within me” is God, then why does Descartes not take the next step that Aquinas does and argue that God as Christ is within us upon our partaking of him at the Eucharist? Descartes does not have answers to these questions, but there are reasons why he does not have answers. While he says that infinite substance is both prior to and more real than finite substance, he never says how the idea of infinite substance can be within the mind – which is finite substance. He does say that the idea of infinite substance proceeds “from some substance which really [is] infinite” (II.31). But he does not describe how it proceeds. What he needs is an account of the logic of analogy for talk about God in order to make sense of how the idea of infinite substance can be in the mind – which, again, is finite substance. For Aquinas, such an argument is analogical – which has at least three consequences in this context. (1) The word substance is applied to God differently than it is to humans. While both God and human beings may be substance, God as substance is 13 See Secada, “Substance in Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy,” 77. different and only analogous to humans as substance. (2) Naming God as infinite, for Aquinas, is only possible via negativa. That is, God is only infinite because creatures are finite. God is not a creature. Therefore, God is not finite. And, logically following (1) and (2), (3) to say that God is infinite substance is to say that God as substance is ontologically different than humans as substance. This ontological difference renders the logic of theological language as only being possible analogically.14 Descartes can account neither for such an ontological difference nor for a logic of analogy for theological language because, for Descartes, substance is not analogically applied to God and creatures. But neither is it applied univocally. As Secada says, Descartes has to “be read as stating that [substance] is applied equivocally to God and creatures. Descartes is explicitly invoking scholastic doctrine, that “substance” is not used univocally of God and creatures, but then holding that it is applied equivocally.”15 A consequence of this equivocal use of substance, according to Secada, “is that, if we know God at all, we know him directly.”16 Descartes’s logic of theological language, then, is neither analogical nor univocal but equivocal. Therefore, in Cartesian theology, we know God directly – unmediated by Christ, the Church, and the sacraments. Since knowledge of God is not analogical, for Descartes, having the idea of God as infinite substance within me results in having God within me because Descartes cannot account for the real difference between the idea of God and God. The ontological difference between God and humanity, the Creator and creatures, is collapsed in For a Baptist defense of the logic of analogy for theological language, see Fisher Humphrey’s Thinking About God: An Introduction to Christian Theology, (New Orleans, Louisiana: Insight Press Incorporated, 1974). 14 15 Secada, “Substance in Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy,” 77. 16 Secada, “Substance in Descartes’s Meditations on First Philosophy,” 77. Descartes’s shift from his first definition of God to his second definition of God. Once this difference is collapsed, the difference between God and the idea of God within me is collapsed also. This collapse renders the sacraments in general and the Eucharist in particular unnecessary for any kind of knowledge of God. The argument that God is present within us is traditionally the function or purpose of the Eucharist: God is most present in us when we partake of God as Christ in the elements of the Eucharist. God is within us because we eat the elements of the Eucharist – which is the body and blood of Christ, the second person of the Trinitarian God. In effect, then, Descartes thinks that God is within us always already – without the need for any act or practice on neither our part nor the part of God. God is within us, then, only because we are human. It is our very humanity that is the only necessity for God to be within us. It is not Christ’s humanity, the Church, nor the Eucharist. By virtue of being human, God is within us. By virtue of our intellect, we know clearly and distinctly that God is within us. But, for Aquinas, God is most present in us sacramentally. That is to say that God is in us because we partake of God as Christ at the Eucharist. Given the words of Jesus, “those who eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them,” I think this sacramental understanding of what it entails for God to be within us – or to abide in us – is more scriptural than the Cartesian understanding of God as being within us always already. God being within us always already in Cartesian metaphysics rids the Eucharist for God to be within us – which may be the most concrete Cartesian influence on the Baptist church given that Baptists interestingly do not think the Eucharist is needed for Baptist life yet think that God as Christ is within every believer. But Baptists need to account for these words of Jesus: “those whom eat my flesh and drink my blood abide in me, and I in them.” IV. Cartesian Transubstantiation Descartes does not address Aquinas’s doctrine of transubstantiation explicitly; he addresses Antoine Arnauld, the Council of Trent, and other “theologians,” but he does not address how he is interpreting Scripture differently than Arnauld or these other “theologians.” Therefore, Descartes’s theory of transubstantiation fails to offer a scriptural account of the Eucharist. In this section, I show how his theory of transubstantiation is simply an abstraction from his own metaphysics. Descartes’s theory of transubstantiation is given as a reply to Arnauld in the “Fifth Set of Objections” to Descartes’s Meditations. Arnauld’s last section in his objections is entitled “Points Which May Cause Difficulty to Theologians,” and “the greatest offence to theologians is that according to the author’s doctrines it seems that the Church’s teaching concerning the sacred mysteries of the Eucharist cannot remain completely intact” (II.152-153). Arnauld continues, We believe on faith that the substance of the bread is taken away from the bread of the Eucharist and only the accidents remain. …Yet the author denies that these powers are intelligible apart from some substance for them to inhere in, and hence he holds that they cannot exist without such a substance. …Further, he recognizes no distinction between the states of a substance and the substance itself except for a formal one; yet this kind of distinction seems insufficient to allow for the states to be separated from the substance even by God (II.153). Arnauld finds Descartes’s theory of substance problematic for understanding the Eucharist because if Descartes is right about substance, the accidents of the bread and wine cannot exist apart from the substance of the bread and wine. If the accidents cannot exist apart from the substance, then either the substance of the bread and wine cannot convert into the substance of the body and blood of Christ or the accidents of the bread and wine cannot remain. Either way, Arnauld thinks Descartes’s Meditations may cause difficulty for theologians considering the possible consequences for the doctrine of transubstantiation. First, Descartes has three responses to the question of accidents that is raised by Arnauld. Arnauld accuses Descartes of not being able to account for how the accidents of the bread and wine remain without the substance of the bread and wine. Although his responses are not very detailed, they provide a good start. His first response to Arnauld is that he has never denied real accidents. For his second response, he claims that there are no definite results concerning real accident in his Meditations. And for his third response, he asserts that God can bring about what God wants. So if God brings about a substantial change in the elements of the Eucharist and not an accidental one, then we may be incapable of understanding it. Descartes comes back to the question of real accidents, but only after he makes some other points. The second point concerns the question of the senses. The question of the senses in Arnauld’s criticism is that it is the remaining accidents of the bread and wine that is perceived by the senses. Because Descartes does not account for real accidents, according to Arnauld, he cannot account for how the senses perceive those real accidents. Descartes has three responses. (1) That which affects our senses, Descartes replies, is only “the surface that constitutes the limit of the dimensions of the body which is perceived by the senses” (II.173). The accidents are not what the senses perceive then, but rather “the surface” – which he discusses in his third point. (2) Contact with objects occurs only at the surface, and that which is perceived by the senses can only be perceived or sensed through contact with objects. So Descartes states the first response in a different way for his second response. It is not contact with the accidents that determines what is perceived or sensed, but it is contact with the object. (3) Descartes applies these first two responses to the Eucharist: “So bread and wine, for example, are perceived by the senses only in so far as the surface of the bread and wine is in contact with our sense organs” (II.174). Descartes changes the question concerning the senses from being about the perception of the accidents in (Aquinas and) Arnauld to the perception of the surface via contact with the object in Descartes. Changing the question is this way begs a lot of questions about “the surface,” and such questions are addressed by Descartes in his third point. Third, there are three descriptions Descartes gives of “the surface.” (1) The surface is not merely the external shape of the body. (2) If “there are any bodies whose nature is such that some or all of their parts are in continual motion (which I think is true of most of the particles of bread and all of those of wine), then the surface of those bodies must be understood to be in some sort of continual motion” (II.174). That is, the surfaces of bread and wine are in continuous motion if the bread and wine are in continuous motion. (3) The surface of the bread and wine is simply the boundary that is conceived modally and not in reality. It is conceived modally because the surface of the bread and wine is conceived and not perceived – that is, it is a conception in the mind and not a perception of a real surface. That which is conceived at all, for Descartes, is conceived modally. Given what is established in the second and third responses by Descartes, the possibilities for transubstantiation can be considered. As his fourth response, Descartes entertains three possibilities for transubstantiation. Possibility #1: the “new substance is contained within the same boundaries as those occupied by the previous substances” (II.175). Possibility #2: the new substance “exists in precisely the same place where the bread and wine were” (II.175). And possibility #3: given specifically that the surfaces of the bread and wine are in continuous motion if the bread and wine are in continuous motion, the new substance exists “in the same place where they would be if they were still present (II.175). Whatever the case may be concerning these possibilities, Descartes does know that our senses would not be affected any differently with the new substance. In other words, Descartes thinks that transubstantiation does not affect our senses differently in any way. Descartes’s fifth response concerns the teaching of the Church at the Council of Trent – which claims: “‘the whole substance of the bread is changed into the substance of the body of our Lord Christ while the form of the bread remains unaltered’” (quoted by Descartes, II.175). Descartes thinks that this use of “‘form’” is unclear because what is form if not the surface that is common to the individual particles, Descartes asks. So Descartes understands the form of bread and wine to be that which is common to the individual particles of bread and wine. His response to the Council of Trent is thus three-fold, and it makes clear his differences with the Aristotelianism of Aquinas’s doctrine of transubstantiation. (1) Following Aristotle, Descartes argues that contact occurs only at the surface. (2) Christ’s body is not contained precisely within the same surface that contains the bread but is present in the bread only sacramentally. Although Aquinas would agree with Descartes’s language that Christ is present sacramentally, for example, he would not agree with Descartes that Christ being present sacramentally entails the denial that Christ’s body is in the same surface of the bread. That Christ’s body is in the bread sacramentally, for Aquinas, is exactly why the substance of the bread is converted into the substance of the body of Christ. So although Aquinas and Descartes use the same language of Christ’s body being present sacramentally, Aquinas would think that Descartes fails to understand the ramifications of Christ being present sacramentally. And (3) the forms of the bread and wine that remain in the sacrament of the Eucharist are not real accidents, “which miraculously subsist on their own when the substance in which they used to inhere has been removed” (II.175-176). Here Descartes brings real accidents back into the discussion, and that carries over into his sixth response. So sixth, Descartes thinks that theologians mistakenly assume that real accidents are real in the sense that they are real and distinct apart from substances. Such an argument, Descartes thinks, rests on a contradiction: “in supposing that objects, in order to stimulate the senses, require anything more than the various configurations of their surfaces: for it is self-evident that a surface is on its own sufficient to produce contact” (II.176). By making the issue about the perception of accidents and not surfaces, the theologians cannot then go on to say that the accidents are all that are perceived by the senses if the accidents are distinct from the substance of the object. Furthermore, Descartes says, “the human mind cannot think of the accidents of the bread as real, and yet as existing apart from its substance, without conceiving of them by employing the notion of a substance” (II.176). In order for accidents to be real, they are necessarily substantial in some sense because to be real at all is to be substantial. So accidents cannot be both real and distinct from substance because to be real is to be substantial. Therefore, there are only real accidents if accidents are not distinct from substances. Descartes’s seventh point is his conclusion to his theory of transubstantiation. “God, the creator of all things, is able to change one substance into another, or in supposition that the latter substance remains within the same surface that contained the former one” (II.177). In this passage, Descartes is suggesting that either God brings about transubstantiation or there is no transubstantiation at all. That is to say that the substance of the bread and wine changes into the substance of the body and blood of Christ if and only if God exchanges one for the other. Or there is surface sharing (my phrase) between the bread and wine and the body and blood of Christ. The elements of the Eucharist, for Descartes, simultaneously and substantially contain both the bread and wine and the body and blood of Christ.17 V. The Cartesian Imagination in Baptist Life Descartes concludes his theory of transubstantiation by saying that the theory of real accidents ought to be rejected “while my theory will be accepted in its place as certain and indubitable” (II.177-178). Descartes got his wish, for the most part – if not from his people, then at least from my people. I think that the parts of Descartes’s theory that either have been accepted in Baptist life and theology or have been used in Baptist Descartes’s theory of transubstantiation is not a defense of consubstantiation although it seems like that given that consubstantiation is the doctrine that while the bread and wine remain both substantially and accidentally, the substance of the body and blood of Christ coexists in, with, and/or under the substance of the bread and wine. Descartes’s theory is not consubstantiation, then, because consubstantiation still relies on the Aristotelian categories and uses of substance and accident. Moreover, Descartes does not think that the substance of the body and blood of Christ coexists in, with, and/or under the substance of the bread and wine but rather the substance of the body and blood of Christ shares the surface of the elements with the substance of the bread and wine. 17 life and theology to shift even further away from the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation are the following. (1) Our senses are not affected, nor are we affected, any differently whether or not the elements are bread and wine or the body and blood of Christ. (2) Baptists think that Christ’s body is not contained within the same surface that contains the bread. In this sense, then, Baptists have gone further than Descartes does in the sense that Descartes argues Christ’s body is contained within the same surface sacramentally that contains the bread whereas Baptists do not think that Christ’s body is contained within the same surface at all that contains the bread. That is why talk of transubstantiation is not needed at all for Baptist theology: at their surface, according to Baptists, the bread and wine is bread and wine and not the body and blood of Christ. (3) Baptists think that Christ’s body is contained in the body of the individual believer always already. Therefore, like the Cartesian God of the “Third Meditation,” God is not most present in us at the Eucharist. God is in us and is thus contained within us like he is contained in the surface of the bread and wine in Cartesian transubstantiation. Given this Cartesian imagination in Baptist life, I think we need to ask ourselves some questions as Baptists. For example, how did we get from trying to account for the words of Jesus in John 6 to the Cartesianism of Baptist life and thought that seemingly disregards these words of Jesus – or, at best, allows them to only be ‘spiritual nourishment’? How did we get away from the Johannine road of salvation where some practice of eating and drinking the body and blood of Christ is needed for our salvation? Why do we think that God is present in us always already rather than listening to the words of Jesus that he abides in those who eat his flesh and drink his blood? Why do we think that the elements are ‘merely symbolic’ when such language is never found in Scripture? Perhaps what we need is better engagement by Baptists with the Christian tradition with Scripture as our guide and standard. I have tried to show in this essay that such an engagement might produce some unlikely allies. In the case of the Eucharist, I think that Saint Thomas Aquinas is one of those allies. His doctrine of transubstantiation is not merely an Aristotelian explanation of the Eucharist. It is a thoroughly scriptural account of the Eucharist – an account that might help Baptists teach children and all believers in the Baptist Church how the Eucharist is an ecclesial practice based on the words of Jesus found in John 6 – that is philosophically sophisticated enough to handle the questions raised by the biblical claim that the bread and wine is the body and blood of Christ.18 I wrote an earlier version of this essay for Jorge Secada’s class on “Cartesian Metaphysics” at the University of Virginia, and I am in debt to Prof. Secada for comments and a long conversation on that version as well as teaching m how to read Descartes. I am in debt also to Aaron James for comments on yet another version of this essay. Angela McWilliams Goodson, Beth Newman, and Omer Shaukat were all good conversation partners and helped me clarify what I wanted to say about Baptist theology and Cartesian metaphysics. Howard Pickett, Frank Rice, and Don Wester raised questions that helped me clarify particular points. Both constantly and continually, Peter Ochs has provided me with the conceptual tools for clarifying the relationship between Scripture and tradition, and I have tried to display in this essay what I have learned from him about that. Lastly, the Young Scholars in the Baptist Academy meeting provided an ideal group in the ideal setting of Oxford for me not only to work out my proposal here but also to provide me with a concrete community of inquirers who are remaining faithful to Christ by serving his Church and the people called “Baptist.” I am grateful especially to the following people from that group: Paul Fiddes for his wonderful hospitality, Roger Ward for all of his work to make the meeting happen, and Margaret Tate for her comments on this essay. I only wish that I could have implemented in this essay all that I learned from being a part of that group. 18