Celestina Savonius

advertisement

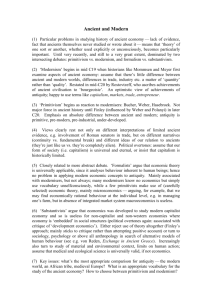

Ancients and Moderns in the Apologetics of the Church of England, c. 1660-c. 1725 In early modern England, those engaged in religious polemic and apologetics frequently compared and even conflated the religious behavior of the Christians of late Antiquity with that of the contemporary “common people,” although they were separated by more than a millennium. My proposed paper examines a neglected strand of this discourse during the Restoration and the early Georgian period. I focus on apologists who accorded a new importance to contemporary "folk" religious practices as remnants or "remaines" of Christianity in its ancient and pure form. The “common people” thus came to be seen as a repository of valuable cultural capital long before the emergence of what we now think of as Romantic nationalism. Historians of religion have, of course, long drawn attention to the Reformers’, and later the Puritans’, denunciation of what they saw as thinly-veiled paganism amongst their unlearned and misguided fellow Christians. Reformation polemic gave rise to a body of quasi-ethnographic descriptions of contemporary religious behavior apparently documenting wholesale adoption of pre-Christian practices by the Roman Catholic Church, the so-called “conformity between modern [Roman Catholic] and ancient [pagan] ceremonies” (to quote from a title which was still on Church of England clergymen's reading lists at the end of the eighteenth century). It is striking, however, that when similar accusations were leveled against established Church of England praxis, Henry Hammond and other apologists anchored their defense in arguments about the ancient form of Christianity which had first been introduced to the peoples of Great Britain, before the “corruptions” of Rome crept in. In crafting arguments to answer not only the scruples of fellow Protestant, but also Roman Catholic accusations of novelty and schism, they turned the Reformation polemic of pagan borrowings on its head, presenting traces of such cultural transfer as evidence of antiquity rather than of corruption. The religious behavior of the “common people”—the very customs and practices most abhorred by Puritans, such as seasonal festivities, processions, lighting candles in churches, kneeling, bowing towards the altar, ringing church bells, and various funeral customs—could be pressed into service as evidence of an unbroken continuity of praxis from early Christianity to their own times. My paper, then, recovers what was, in early modern England, a new variant among rival uses of antiquity, one which transformed the modern countryman into a living ancient. Celestina Savonius-Wroth, Indiana University Bloomington