NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE

advertisement

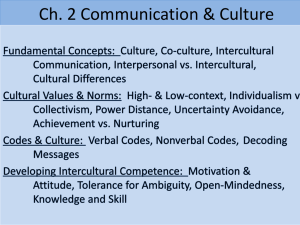

NONVERBAL COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE As Hall (1984) mentioned, the primary level of culture is communicated through nonverbal means, because imitation and observation are the two major ways for us to learn aspects of our culture through the socialization process rather than by means of explicit verbal expressions. Nonverbal communication is a subtle and mostly spontaneous and unconscious process in which we are not aware of most of the nonverbal behaviors we enact (Andersen, 1986). Thus, unlike verbal language, it is very difficult for us to master the other culture’s nonverbal behaviors. However, the rules that govern verbal and nonverbal communication are similarly subject to the variations of culture. Significantly, that which is learned by imitation is least within our awareness. Thus, if a person says “1+1=4,” we may correct him or her, and our reaction is probably nonemotional. However, we react emotionally to violations of what seems “natural” to us. When we are left waiting “too long,” or “stared at,” our reaction may be anger. According to Samovar and Porter (1994), culture and nonverbal behaviors are interrelated in two ways. First, nonverbal behaviors are dictated by the communicator’s culture. As noted earlier, a nonverbal symbol possessing a positive meaning may become negative in another culture. Silence as a nonverbal expression also receives an opposite perception in different cultures. People of Western culture strongly perceive silence as a negative attribute (Ishi & Bruneau, 1994). For example, North Americans tend to interpret silence as sorrow, critique, obligation, regret, and embarrassment (Wayne, 1974). Conversely, the Japanese highly value silence. Ishi & Bruneau (1994) reported that a study by Japanese scholars shows that silence is a key to success for Japanese men, and over 60 percent of Japanese businesswomen said that they prefer to marry silent men. Second, culture determines the appropriate times to display nonverbal behaviors, emotions in particular. For example, the Chinese and Japanese react much less strongly to provocative events compared to their counterparts in Western societies. Uninhibited emotional display is considered by the Chinese and Japanese as being disruptive and dangerous. It not only contradicts cultural values such as hierarchy and harmony but also puts the person in a facelosing and embarrassing situation (Bond, 1991). To explain differences in nonverbal behaviors in terms of cultural variations, Andersen (1994) distinguished the following dimensions of culture: contact/low contact, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, power distance, and high/low context. People in contact cultures display immediacy behaviors that express warmth and availability for communication; they emphasize interpersonal closeness. In contrast, people in low-contact cultures use less touch and tend to stand apart in communication. Nations in warm geographic areas, such as those in West Asia and the Mediterranean region, are more likely to exhibit more contact. Nations with cool climates, such as most Northern European countries, tend to be low-contact cultures. Individualistic and collectivistic cultures show a certain degree of difference in nonverbal behaviors. Andersen (1994) indicated that in terms of using space, people in individualistic cultures tend to be distant and remote, while people in collectivistic cultures are likely to be interdependent and proximically close. Regarding body activities, people from individualistic cultures smile more than people in collectivistic cultures (Tomkins, 1984). One of the explanations for this difference is that emotional displays are more likely to be avoided in collectivistic cultures. Argyle (1975) also pointed out that kinesic behaviors are more synchronized in collectivistic cultures, because working collectively requires that movement and actions be highly coordinated. The dimensions of masculinity/femininity and power distance also affect kinesic and paralinguistic behaviors. For example, in egalitarian or feminine cultures women tend to have more relaxed vocal patterns and less tension exists between the sexes (Lomax 1968). In addition, in high-power-distance cultures touch between males and females is discouraged. Body tension in subordinates in high-power-distance cultures is also apparent (Andersen & Bowman, 1985). Finally, Andersen (1994) indicated that people in high-context cultures are much more sensitive to nonverbal cues. They are much more able to read and perceive nonverbal behaviors than males in low-context cultures. This ability leads them to expect their low-context communication counterparts to understand environmental cues and hidden and subtle gestures and feelings that are not recognizable in the latter’s culture. The last section of this chapter will focus on acquisition of nonverbal skills that can be applied to intercultural communication. Research Highlight 5—3 Who: Andersen, P.A. What: “Explaining Intercultural Differences in Nonverbal Communication.” Where: In L.A. Samovar & R.E. Porter (Eds.) (1994), Intercultural Communication: A Reader (pp. 229—239). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. This article reviews the code of nonverbal communication and the influence of culture on interpersonal behavior, and delineates five main dimensions of cultural variation that affect nonverbal communication. Six nonverbal codes of intercultural communication are (1) chronemics—the study of meanings, usage, and communication of time, (2) proxemics—the study of space and distance in communication, (3) kinesics—the study of body movements or body activities, including facial expressions, eye contact, gestures and body posture, (4) physical appearance—the most important element that affects our perception in the initial intercultural encounters, (5) vocalics, or paralanguage—the study of voice or vocal signs, and (6) olfactics--- the study of smell in communication. Culture shapes our behavior in an enduring, powerful, and invisible way. Culture is a critical concept to communication study, because we are a product of our culture. In order to understand cultural differences in nonverbal behavior we can locate cultural variations along five dimensions: 1. Immediacy and expressiveness—Immediacy or expressive behaviors refer to actions that communicate warmth, closeness, and availability for 2. 3. 4. 5. communication. High-immediacy cultures are also called contact cultures, and low-immediacy cultures low-contact-cultures. Research shows that contact cultures tend to locate in warm-temperature areas (e.g., most Arab countries) and low-contact cultures in cool climates (e.g., most Northern European countries). Individualism versus collectivism—Research has found that people in individualistic cultures tend to be more remote and distant proximically, and more nonverbally affiliative. People in collectivistic cultures tend to work, play, live, and sleep in close proximity to one another, tend to be synchronized in kinesics, tend to suppress extreme emotional display, and tend to stress groupness and cohesion in their singing styles. Masculinity—Research indicates that women in low-masculinity cultures show more relaxed vocal patterns, more vocal solidarity and coordination in their songs, and more synchrony in their movement than those in high-masculinity cultures. Power distance—Research shows that high-power-distance cultures tend to be more “untouchable” (in terms of tactile communication), tend to be more tense in subordinates’ body movement, tend to smile more for subordinates to appease superiors or to be polite, and tend to be more aware that vocal loudness may be offensive to others. High and low context—Research finds that in high-context cultures people tend to be more implicit in verbal codes, tend to perceive highly verbal persons less attractive, tend to be more reliant on and turned into nonverbal communication and expect to have more nonverbal codes in communication. In conclusion, applying cognitive knowledge of cultural variations in actual encounters with people from different cultures is the best way to achieve intercultural communication competence.