SCIENCE, VALUES AND FEMINISM After reading Kuhn, we may

advertisement

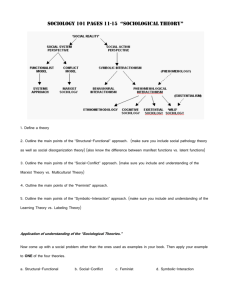

SCIENCE, VALUES AND FEMINISM After reading Kuhn, we may have become convinced that science is more than just logic + observation: How do we understand talk of unobservables? The actual practice of science seems more complex than this. So positivism and Popper’s views on science seem incomplete. Kuhn gives us a more subtle and realistic picture of scientific method, but it has some problems: If values play a part in paradigm acceptance, how can science tell us anything about the objective world? 1 Rationality Many took Kuhn’s ideas as a death-blow to the notion of scientific rationality. If social, personal, institutional, etc. forces play an ineliminable role in determining which theories are accepted, can scientific claims be objectively grounded? Won’t it be possible for biases to play a key role here? Recall Duhem-Quine: any thesis can be rejected or accepted with enough revision elsewhere. 2 Social context Longino argues that both the positivists and Kuhn fail to appreciate the extent to which science is a social activity: For positivists science is a matter of applying logical rules to observation— individuals can do this. For Kuhn, communities working in different paradigms can’t meaningfully communicate to each other. Yet, a fuller appreciation of the social nature of science can lead to a realistic and robust conception of scientific objectivity. 3 The social nature of science Three aspects in which science is, according to Longino, essentially social in character: 1. Scientific disciplines are social networks 2. Scientists are initiated into a discipline by training and education 3. Scientists and disciplines exist in and interact with society as a whole (e.g. to secure funding). 4 Science as a social exercise Longino argues that what comes to be called scientific knowledge is the result of a complex interaction between many people: The gathering of data is typically conducted by groups/labs. Even if an individual could do this, the process by which the results come to be called “knowledge” is irreducibly social: Hypothesis/results are subjected to peer-review. Once published, they are subjected to scrutiny—others try to duplicate results, expand them, employ them in other tasks, etc. We can think of it this way: scientific ideas become accepted as facts only after surviving in the “marketplace” of ideas and criticism. 5 Public knowledge As a result, scientific hypotheses are public property: As social interaction stabilizes a claim, it is therefore available for others to examine The facts against which claims are tested are (taken to be) mindindependent. In other words, social forces: Rely on a common language of assessment. Restrict the range of legitimate claims to those that concern what is accessible to others. This will, for Longino, point the way toward objectivity even when social factors influence science. 6 The nature of criticism Scientific conclusions can be criticized in various ways: Were the data collected properly? Do they support the conclusion? Is the hypothesis conceptually sound? Is it consistent with accepted theory? But here is a deep, foundational question: How do we know that any piece of evidence is (ever) relevant to a conclusion? Here is why Longino think this question is important: 7 Interpretation and background beliefs Empirical data or observation needs interpretation: Which conclusions they bear on does not come to us via the microscope. But such interpretation necessarily imports background beliefs: We have to start our interpretation somewhere. So, the very presence of empirical observation does not secure objectivity (contra positivism). This is (in part) why Kuhn seems threatening to objectivity. 8 Social Objectivity However, Longino has an answer to this worry. Since science is thoroughly social, even such background beliefs are put into the marketplace of criticism and so can be corrected and modified. This process will, over time, weed out any subjective bias or eccentricity from scientific reasoning. So, science is objective to the extent to which the background beliefs of researchers, labs, communities, etc. are able to be modified, improved, dropped, and so on. Objectivity is a matter of degree. 9 Requirements for social objectivity The danger is that criticism will scare off dissent and merely encourage conformity. In order for scientific-social interaction to be objective rather that silencing, argues Longino, various conditions must be in place: First, we must ensure that there are recognized forums for criticizing research, not just presenting research. Secondly, critics (and their targets) must be able to appeal to shared standards (otherwise criticism might be simply idiosyncratic and go unheeded). E.g. empirical adequacy, consistency, generality, etc. It is not necessary that there is agreement on every point, just some possibility of genuine interaction 10 More criteria Thirdly, the community as a whole must be willing to respond to criticism by updating its beliefs. Individuals can continue to defend their views, but the community must be willing to evolve over time. Finally, the widest possible diversity of viewpoints must be admitted into the arena of criticism. No perspective may be eliminated or included on the basis of political power, money, gender, ethnicity, etc. Why? Only if as many scientific ideas as possible are considered can we be confident that the view which survives is the best one to adopt. If any groups are excluded, it is likely important perspectives will be too. 11 The nature of objectivity For Longino, objectivity is not a feature of any particular hypothesis or logical theory taken on by a scientist. Rather, objectivity is a property of the method used to arrive at a scientific belief. If the method has the characteristics she outlines, it does not follow that the resultant beliefs are true. They will, however, be the best justified beliefs we can have. 12 Some restrictions Some things which limit criticism: If a debate becomes stuck in repetitive arguments, or has no clear connection to an empirical program, it will eventually be ignored—it cannot appear interminable. Financial inducement: if there are large rewards for finding result R, then criticism of R will tend to be downplayed (e.g. pharmaceuticals). If any view receives universal acceptance, then it will hardly be criticized. What will be needed is someone who doesn’t share the outlook. Upshot of all of this for Longino: the more perspectives that exist in the scientific community, the greater the likelihood of objective results, results free of individual preferences or bias. 13 Feminist views on (biological) science Background bias in science has been well highlighted by many feminist philosophers. Hence, the feminist perspective provides us with an opportunity to examine the concept of scientific objectivity. 14 Some examples of bias “Sleeping beauty” model of fertilization: Unquestioned for years, despite pictures of microvilli extending from sear urchin eggs. “Man as hunter” theory of tool development: Ignores imperative to develop tools to rear young or prepare food. Nineteenth century attempts to prove that female’s are biologically determined to be less intelligent: This continued despite repeated failures of experiment—data was reinterpreted to fit assumptions Attempts to depict female skeletons as inherently different from male skeletons: Many differences more likely due to social factors such as corset-wearing or lowered nutritional intake. 15 What the examples show Okruhlik: what such examples demonstrate is that background beliefs, biases or commitments: Can impact which hypothesis are even considered, which questions asked, which data ignored or taken as relevant. In other words certain beliefs about the place of women compared to men seem to have had a substantial impact on the content of scientific theories. This only comes to light in comparison with rival hypothesis that import different (conflicting) background commitments. 16 Bias and scientific content As we have seen, it is plausible to suppose that science is a subtle activity. Observations require interpretation Failed predictions can be dealt with in many ways—by adding auxiliary hypotheses, or revising other parts of the theory (Duhem-Quine), etc. The feminist perspective has shown us how a particular bias has played a role in preventing certain views from being considered. So, even if there were a perfectly objective way of deciding between theories by applying scientific rules, it could still be the case that we are only presented with a biased selection of theories to choose from! 17 Traditional feminist responses Feminist empiricism: androcentric bias results from the failure to apply scientific methods properly. We just need apply scientific techniques more rigorously to eliminate biases. Standpoint epistemology: some viewpoints are epistemically superior to others. E.g., those who benefit from current set-ups will be less willing to acknowledge revolutionary evidence. Hence, ‘outsiders’ (e.g. women) will produce better, i.e. less biased, science. Feminist postmodernism: there is no single standpoint of all women. There are only irreducibly many perspectives on reality, none of which can be said to be superior to others. There is no single, objective viewpoint that science can attempt to attain. 18 Hypothesis testing Okruhlik: testing a theory is a comparative affair—we can only test a theory against existent rivals in the same area. We can’t compare a theory to bare reality to get a yes/no answer. We can, however, pick T1 over T2 on the basis of what we’ve observed. Note: Popper would disagree, but not Lakatos 19 Rational choice But here is Okruhlik’s point: even if there were a perfectly objective, rational method of choosing between hypotheses, the theories that exist to choose from might be the generated in a biased manner. Since most accounts of science focus on how theories are justified, they have little, if anything, to say about how they are brought forth. In fact, they tend to consider the context of discovery to be irrelevant to rationality and objectivity. What matters is how theories are justified (context of justification). 20 Upshot Since contextual values can influence theory generation, they can impact the content of science. So, any scientific method that ignores the context of discovery will be unable to eliminate all potential bias from science. It seems that we want to find a way to address the bias that precedes scientific method. The alternative is to accept that bias will not be eliminated from science and so isn’t as objective as we might have thought. Okruhlik thinks we can address bias in theory generation. 21 A proposed solution Okruhlik: what we need is to ensure that a variety of viewpoints are involved in theory generation. Historically excluded groups need to bring their social and political viewpoints to the scientific enterprise. We need to make sure that the scientific community includes as wide a range of perspectives as possible so that as many theories as possible are proposed for evaluation. This may, e.g., involve affirmative action policies for women and minorities. 22 Not a traditional view This position differs from feminist empiricism: Current methodology can’t eliminate bias (it ignores theory generation). The stance is non-individualistic: the solution is to include many perspectives in the community. It differs from standpoint theory: There are no privileged perspectives (we simply want as many as possible). Men could achieve this plurality of viewpoints; it is just less likely to occur than if we include women. It differs from postmodernism: Okruhlik seeks to improve on scientific objectivity, not reject the possibility. 23 Summing up The scientific picture painted by positivists (Ayer, Hempel) and Popperians (Popper, Lakatos) suggest that the justification, confirmation, corroboration, falsification, etc. of theories is: Individualistic: any single person can be scientifically rational Universal: there is one method for all. Kuhnian and feminist critiques cast doubt on this picture. They suggest we either reduce or broaden our conception of scientific rationality and objectivity. Both Okruhlik’s and Longino’s views are consistent with realism, the view that scientific theories tell us how the world is in itself. Kuhn’s views cast doubt on this. We shall address the realism/antirealism dispute next week. 24