BONUS ARMY

advertisement

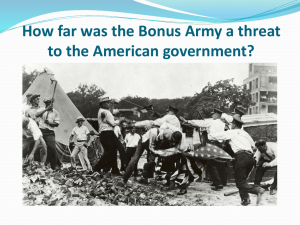

March of the Bonus Army Director: Robert Uth PBS. 30 minutes. 2006 The images are heartbreaking: Mounted troops and advancing soldiers level bayonets and spray tear gas on protesting World War I veterans. Having survived the German gassing in the trenches a little more than a decade previously, these men seeking reparations for their service now face a similar threat in the shadow of the White House. The story of the so-called Bonus Army’s ill-fated protest marches on Congress in the spring and summer of 1932 is too little known. Now, thanks to a new documentary, March of the Bonus Army, it comes to vivid and gut-wrenching life. To the mournful strains of “Brother Can You Spare a Dime” (a song directly inspired by these events), this 30-minute film begins with the conscription of soldiers in 1917 and concludes with the Franklin Roosevelt’s signing of the G.I. Bill of Rights in 1944. What transpired in those intervening years is still hard to watch and difficult to believe. . . . The Bonus March, in the words of the film, was “the march that changed a nation.” By the spring and summer of 1932 the Depression was deepening. Political leadership was drifting, and the Hoover White House seemed paralyzed and frustrated. It was as if the President was missing in action after diagnosing the Depression was just a state of mind and declaring that “prosperity was just around the corner.” At precisely this time, during the spring and summer of 1932 an estimated 45,000 World War I veterans, their families, and other sympathetic groups marched on Washington, D.C. seeking redress for “reparations” that had been promised them by the Adjusted Service Certificate Law of 1924. Too impatient to wait for 1945, when the money had been originally promised, they were led by Walter W. Waters, a former Army sergeant and supported by retired Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler, a popular figure of the day. This so-called Bonus Army gathered at the Capital Building on the 17th of June as the Senate was prepared to vote on a bill which had already been passed by the House of Representatives and which would have moved forward the time when the veterans could receive their cash bonuses. However, when the Senate blocked the bill, many of the marchers remained and resisted removal from a federal construction site. A fight broke out between marchers and the police, resulting in the deaths and wounding of several marchers and police. It was at this point that President Herbert Hoover ordered federal troops armed with unsheathed bayonets and tear gas, under the overall command of General Douglas MacArthur, to repel the protestors. Several veterans were killed and hundreds more injured as the soldiers marched into Anacostia. As a result of the shock effects of this unprecedented rout, Hoover’s re-election campaign was fatally damaged. After the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, members of the Bonus Army returned to Washington to renew their claims. But Roosevelt vetoed the early payment. It wasn’t until 1936 when public sentiment forced Congress to override Roosevelt and make the early bonus payments a reality. All this is vividly evoked in The March of the Bonus Army’s amazing mixture of editorial cartoons, newspaper headlines, testimonials by many historians; and newsreel footage of the arriving veterans, their tent cities, their protests, and their brutal treatment at the bayonets of MacArthur’s soldiers. Even for those who may know the general outline of this event, there are surprises here: The marchers argued for what they called “adjusted compensation” for their wartime service, not for a “bonus.” African American veterans, who were kept segregated during the war, found themselves welcome recruits in the makeshift dwellings of the Anacostia tent city, where “the thread-bare heroes of World War I formed their last great encampment.” One of those responsible for repelling the marchers, Washington police chief Pelham Glasford, vocally sympathized with them (“They followed their leaders in the child-like faith that their government might help them, just as they had responded during the War.”) And we learn that, despite no supporting evidence whatever, President Hoover branded the March as Communistinspired. And standing amidst it all, in a sharply-focused image, is General Douglas MacArthur, stiff and resplendent in his spiffy full-dress uniform. . . . Memories of this tragedy were still vivid when a curious motion picture was released in March of 1933, just a few days before Roosevelt’s inauguration. Gabriel Over the White House, produced by William Randolph Hearst’s Cosmopolitan Pictures and released by Louis B. Mayer’s MGM, referenced the plight of the Bonus Marchers, although never mentioned them by name. As a part of the pledge by newly elected President Hammond (Walter Huston) to take whatever measures he deems necessary to pull America out of the Depression (including declaring martial law and establishing himself a dictator), he meets an army of jobless protesters gathered to march on Washington demanding work. He promises them recruitment in what he calls “an army of reconstruction.” Alas, Hammond’s promise was merely a screen fiction. In real life American veterans would have to wait until 1944 and the G.I.Bill before they could be guaranteed compensation for their sacrifices. Perhaps hereinafter both films should be shown together in the classroom. They demonstrate how reality and fiction sometimes suffer a tragic disconnect. John C. Tibbetts University of Kansas