FORMAL CORRESPONDENCE VS

advertisement

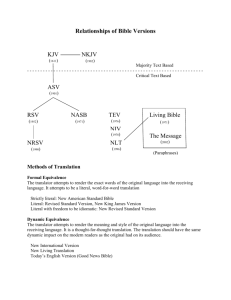

VLADIMIR IVIR FORMAL CORRESPONDENCE VS. TRANSLATION EQUIVALENCE REVISITED In: Even-Zohar & Gideon Toury (1981) Theory of Translation and Intercultural Relations, University of Tel Aviv (= Poetics Today 2:4), p. 51-59 The two concepts which feature in the title of the present paper belong to two different, though (as will be shown) by no means unrelated, activities. Formal correspondence is a term used in contrastive analysis, while translation equivalence belongs to the metalanguage of translation. In principle, perhaps, the two terms could be discussed separately in their two disciplines, and it is indeed possible to imagine a theory of translation which would operate with the concept of equivalence defined without reference to formal correspondence, just as it is possible to imagine contrastive analysis which would rely on the concept of correspondence established without the use of translation. In practice, however, both terms have been found necessary by students of translation and by contrastive analysis. Issues that are raised in connection with formal correspondence and translation equivalence are certainly more than just terminological: a discussion of formal correspondence in translation concerns the role of linguistic units in translation and the place of linguistics in translation theory, while a discussion of translation equivalence in contrastive analysis concerns the role of translation in contrastive work. The relationship between them has been discussed by Catford (1965) from the point of view of translation theory and by Marton (1968), Ivir (1969, 1970), Krzesowski (1971, 1972), Raabe (1972) from the point of view of contrastive analysis. 1 Our understanding of the concept of translation equivalence will depend on the view we take of translation itself. Looking at translation as a result or product, faced with two texts one of which is a translation of the other, we might be tempted to conclude that translation is «the replacement of textual material in one language (SL) by equivalent textual material in another language (TI.)» ... or more generally that it is « the rendition of a text from one language to another» (Bolinger, 1966: 130). Equivalence would then exist between texts – i.e., it would hold together chunks of textual material or linguistic units (texts being simply linguistic units of a higher order than the smaller units which compose them). This is a static view both of translation and of equivalence: pushed to its extreme, it forces in the conclusion that for any linguistic unit (text of portion of a text) in the source language there is an equivalent unit in the target language and the it is translator's job to find that unit. Hence the search for different textual types and their characteristics in different languages. Another picture of translation and translation equivalence is obtained when a dynamic view is taken and translation is regarded as a process rather than as a result. One then speaks about substituting messages in one language for messages in some other language (Jakobson, 1959: 235), about «reproducing in the receptor language the closest natural equivalent of the message of the source language» (Nida, 1969: 495), or about «the nature of dynamic equivalence in translating» Nida, 1977). This letter view of translation is the communicative view, and it sees, translation equivalence not as a static relationship between pairs of texts in different languages but rather as a product of the dynamic process of communication between the sender of the original message and the ultimate receivers of the translated message via the translator, who is the receiver of the original message and the sender of the translated message, Messages are configurations of extralinguistic features communicated in the given situation. The original sender starts from these features and – relying on the resources of his language, on his command of that language, and on his assessment of the nature of the sociolinguistic relationship between him and his (actual of potential) receivers – codes them to produce the source text. The coded message (source text) reaches the translator through the (spatio-temporal) channel of communication. He decodes it and receives the original sender's message, which he then proceeds to code again in the target language, relying on the resources of that language, on his command of that language, and on his assessment of his relation to the ultimate receivers. Under this view, what is held constant (i.e., equivalent) are not texts but rather messages, and it is messages that the participants return to at every step in the process of communication. The translator, in particular, does not proceed directly from the source text to the target text: rather, he goes from the source text back to that configuration of extralinguistic features which the original sender has tried to communicate as the his message and having arrived there he codes that message again, in a new and different communicative situation, producing a text in the target language for the benefit of the ultimate receivers. Several points must be made in connection with the view of translation and equivalence presented here. First, the nature of the translator's job in receiving the original sender's message does not essentially differ from the job of other source-language receivers of that message, and his job in coding the received message again in the target language is not unlike the task performed by the original sender (only the communicative situation is different, that is, the translator is a different «linguistic person» than the original sender, he uses a different language and codes the message for different receivers than the original sender). Second, messages are not communicated absolutely. The original message undergoes modifications in the process of coding (depending on the potential of the language, the sender's command of that language, and the intended audience), in the process of transmission (owing to the «noise line the channel»), and in the process of decoding (depending on the receiver's command of the language and his ability – coming from the shared experiential background . to grasp the sender's message). Clearly, such modifications also take place when the translator receives the message, when he codes it again in the target language, when he transmits the coded message through the channel of communication linking him with his receivers, and when the ultimate receivers decode the translated message. This relativity of communication – any communication, and not jus that involving translation -. places the concept of equivalence in translation in a new perspective: equivalence holds between messages (communicated by the original sender, received and translated by the translator, and received by the ultimate receivers) which change as little as possible and as much as necessary to ensure communication. Thus, true translation is by no means limited to communicative situations involving two languages. An act of translation takes place each time that a text is produced as a coded expression of a particular configuration of extralinguistic features and is decoded to enable the receiver to receive the message (cf. Steiner, 1975: 47), The third point that can be made about translation equivalence follows from what has just been said: equivalence is a matter of relational dynamics in a communicative act – it is realized in that act and has no separate existence outside it. It can thus be compared to abstract units of the linguistic system, such as phonemes, which do not exist physically outside the speech act in which they are realized and whose realization in speech is somewhat different and is yet produced and received as the «same» phoneme. Or it could be compared to a person's signature; there is no «ideal» signature of a given person, and in each act of signing it comes out a little different visually; yet, it is recognized as «equivalence» with any other of it realizations – allowing for the fact that different realizations take place in different communicative situations. 2 Since translation equivalence is the translator's aim and since it is established at the level of messages, in the communicative act, and not at the level of linguistic units, it may appear that there is no need for the concept of format correspondence in the model of translation presented here. I will argue further below that this is not so and that there is a sense in which formal correspondence holds together the source and target texts. But in order to demonstrate this, a modification of some of the available definitions of formal correspondence will be needed. Catford has defined formal correspondence as identity of function of correspondent items in two linguistic systems: for him, a formal correspondent is «any TL /target language/ category which may be said to occupy, as nearly as possible, the «same» place in the economy of the TL as the given SL/source language/ category occupies in the SL «(Catford, 1965: 32). Marton (1968) and Krzeszowski (1971, 1972) postulated an ever closer relationship between linguistic expressions in the source and target languages – that of congruence which is characterized by the presence, in the two languages, of the same number of equivalent formatives arranged in the same order. Realizing that relying on a concept defined in this way would prevent the contrastive analyst from working with real language (and would thus make his results useless for any conceivable pedagogic purposes), Krzeszowski later (1972: 80) went back to the concept of equivalence. However, he applied it to sentences possessing identical deep structures (i.e., semantic representations of meaning) rather than those which were translations of each other. At the level of deep structures equivalent sentences were also regarded as congruent, their congruence disappearing in later derivational stages leading to the surface structure. Both Catford's «formal correspondence» and Marton-Krzeszowski's «congruence/equivalence» represent attempts at bringing linguistic units of the source and target languages into some kind of relationship for purposes of contrasting, the necessary tertium comparationis being provided by the identity of function or meaning. Without a tertium comparationis no comparison or contrasting of linguistic units is possible, but the question is what can serve as the tertium comparationis. One possibility would be an independently described semantic system whose categories would be held constant while their linguistic expressions in pairs of languages under examination would be contrasted. However, such a system has not yet been proposed and we do not know what its categories might be. Another possibility might be a common metalanguage in terms of which both the source and the target language would be described to the same degree of exhaustiveness. This metalanguage would supply categories in terms of which the appropriate parts of the two systems could be contrasted since the descriptions would be matchable, their contrasting would consist in simply mapping one description upon the other to establish the degree of fit. Again, the descriptions of no two languages meet this requirement. Formal correspondence as defined by Catford can hardly be said to exist: even in pairs of closely related languages it is practically impossible to find categories which would perform the «same» functions in their respective systems, and that probability decreases with typological and genetic distance. Marton-Krzeszowski's concepts of «congruence/equivalence» in fact make use of the metalanguage of the transformational-generative grammar, in particular of the notion of deep structure, to avoid relying on the postulate of translational equivalence. But the postulated of deep structure and transformation are no easier to work with: the status of deep structures is far from clear, as is also the meaning-preserving nature of transformations. So, one falls back on the concept of translation equivalence in one's search for a suitable tertium comparationis for contrastive purposes. (One feels all the more justified in doing this when one observes actual contrastive practice: no matter what they otherwise profess, contrastive analysts begin with sentences which are obviously translational pairs and proceed to demonstrate the bilingual person's, that is the analyst's, intuition of their equivalence.) However, we must remember that translation equivalence holds together communicated messages and not linguistic units used to communicate them and that we must go beyond equivalence to find the necessary tertium comparationis which hold linguistic units together. It has been suggested (Ivir, 1969: 18) that a good candidate for the job would be formal correspondence – but formal correspondence defined not with reference to linguistic systems (as Catford would have it) but rather with reference to translationally equivalent texts. Formal correspondents – to modify Catford's definition given above – would be all those isolable elements of linguistic form which occupy identical positions (i.e., serve as formal carriers of identical units of meaning) in their respective (translation ally equivalent) texts. The difference between language-based and text-based (or system-based and equivalence-based) formal correspondence is seen in the fact that while the former type of correspondents stand in a one-to-one relationship, the relationship in the latter type is on-to-many. Typically, a given formal element of the source language, used in different texts produced in different communicative situations, will have several target-language formal elements which will correspond to it in translated target texts. But it should be realized that precisely for that reason the formal elements which are correspondent in translationally equivalent texts are never matched in totality, as they would be if parts of the systems of the two languages were contrasted. Rather, they are matched in those of their meanings with they participate in the particular source and target texts. The approach to contrastive analysis based on the concept of formal correspondence presented here has been outlined in Ivir (1970) and applied in various papers coming out of the Zagreb-based Yugoslav Serbo-Croatian – English Contrastive Project (cf. Filipović, 1971.). Only a brief description will therefore be given here of what it means for formal correspondents to stand in one-to-many relationships and to be matched only in meanings involved in particular texts. For instance, the Serbo-Croatian instrumental case yields several different correspondents in English translation – the prepositions with, by, on, through, across, along, in, then the subject position of the noun in question, then the plural of the noun in question, the adverb in –ly, etc. Clearly, the different correspondents stand for the different meaning of the SerboCroatian instrument ease: with for instrument (rezati nožem – cut with a knife) or company (doći s nekim – come with someone), by for means of transportation (doći vlakom – come by train), on and/or the plural noun for time. Muzej je zatvoren ponedjeljkom – the museum is closed on Monday/ on Mondays/Mondays), in for mode (pisati tintom – write in ink) in, through, acress, along for place (šetati parkom – walk in the park, prolaziti šumom – walk through the forest, prelaziti poljem – walk across the field, ići cestom – walk along the road), the subject-noun for place (pijev ptica odzvanjao je šumom – the forest resounded with the chirping of birds) or instruments (ovim ključem mogu se otvoriti sva vrata – this key open all the doors), the adverb in – ly for manner (s indignacijom – indignantly), etc. Thus, in looking for formal correspondents in English for the SerboCroatian instrumental case one scans translationally equivalent texts and establishes a list of formal linguistic elements, each of which corresponds not to the Serbo-Croatian instrumental as such but to some particular aspect of its meaning. (It should be noted in passing that such multiple formal correspondents are important analytical pointers to distinctions of meaning in the source language of which native speakers may be unaware. Hence the importance of translation and contrastive analysis for native language description.) But normally the particular aspect of the meaning will not be expressed by means of just one kind of formal elements in the target language (just as it is not the case that a particular meaning will be expressible by only one kind of formal element in the source language – the one-to-many relationship among formal correspondents in pairs contrasted languages is merely a reflection of similar relationships between meanings and linguistic units in single languages). We have already seen, for instance, that the temporal meaning of the Serbo-Croatian instrumental case is expressed in English by the preposition on plus the name of the day in singular or plural, or simply the name of the day in the plural without a preposition but unmistakably in the position of an adverbial adjunct). Differences in meaning may be hardly detectable in some cases (s indignacijom – indignatly or with indignation); they may be slight in other cases (Mondays and on Mondays belong to different varieties of English, while on Monday is potentially ambiguous and may refer to one particular Monday , an interpretation not permitted by the Serbo-Croatian instrumental, or to every Monday), or they may be more appreciable though not quite easy to specify (doći automobilom – arrive by car or arrive in a car). The presence of correspondent formal elements in texts which express equivalent messages is a matter of likelihood, not certainty. In seeking to communicate, in the target-language communicative situation, a message equivalent to the one received in the source language, the translator – as noted earlier – has at his disposal a different potential set of linguistic devices than that used for the coding of the message in the source language. There fore, in a given translated text, some linguistic units of the source text will have no formal correspondents, while the formal correspondents of others will inevitably carry found to be Let’s take the lift, then the search for the English correspondent of the Serbo-Croatian instrumental case is in vain: the message is structured differently, using a verb which does not accept a means-of—transportation construction. In the case of the sentence Doći će popodnevnim vlakom (“He’ll come by the afternoon train”) translated as He’ll come on the afternoon train, the preposition on focuses on an aspect of meaning not in the focus of the Serbo-Croatian instrumental. In view of what has just been said, a procedure is needed that will enable the contrastive analyst to isolate formal correspondents in translationally equivalent texts. The recommended procedure is that of back-translation (Spalatin, 1967), which is intended to serve as a check on the semantic content. Because of its function, back-translation, unlike translation proper, does not deal with messages but with formal linguistic elements isolated from the target text, which are then translated back into the source language to give the corresponding linguistic element of that language. Back-translation can thus be defined as one-to-one structural replacement. This means that an element of form isolated from the target language as a likely candidate for a formal correspondent of an element in the source text is translated literally and only once) back into the source language to see if it will yield exactly that element whose correspondent it is though to be. Thus the translated expression come by train back-translates as doći vlakom and we know that the by-construction is a formal correspondent of the means-oftransportation instrumental in Serbo-Croatian. But when the translated sentence He’ll come on the afternoon train is back-translated into Serbo-Croatian, we get Doći će na popodnevnom vlaku, which is understood by native speakers, correctly, as having an element of meaning that Doći će popodnevnim vlakom does not have, but which they can hardly accept as a grammatical sentence of Serbo-Croatian. The lack of grammaticalness does not matter since we are dealing with structural replacement, not translation in the ordinary sense. What does matter is that the meaning is not quite the same, because in expressing this particular message English reveals an aspect of the real woeld which SerboCroatian does not. Is the contrastive analyst to conclude from this that the on-construction is not to be accepted as the formal correspondent of the means-of-transportation instrumental (that is, that the establishment of translation equivalence has necessitated structural changes between the source and target texts involving the disappearance of any formal trace of the source-text instrumental)? The answer to this question would have been positive if the translator had been free to use the by-construction but had for some reason failed to use it. But when , as in this case, the translator could not very well have used it and at the same time ensure the translational equivalence of messages (because the by-construction would have been less natural than the instrumental case was in the original and equivalence would have suffered), the formal element which he did use is accepted as a correspondent. The shift is meaning which it brings about and the exact conditions of its use are precisely what contrastive analysis should elucidate. A sufficiently large corpus of translationally equivalent texts will .. Supply further examples of formal correspondence to make generalizations possible. In the case of the means-of-transportation instrumental, for instance, one will find doći automobilom translated ase arrive by car doći vlastitim automobilom as arrive in one’s own car and doći automobilima as arrive in cars, which seems to indicate that no restricitions are placed on the use of the Serbo-Croatian means-of-transportation instrumental, while the English by-construction is largely restricted to unmodified nouns of this class in the singular. Moreover, the class of nouns admitted in this construction is broader in Serbo-Croatian than in English, as illustrated by examples like the following: putovati prvim razredom – travel by first class. 3 The preceding section has shown how translation equivalence enable the analyst to isolate formal correspondents which are the contrastively analysed. An indication of the actual contrastive procedure has also been given, but is full description is outside the scope of the present paper. What remains to be shown now is how contrastive correspondents (and the results of contrastive analysis) are used in translation. It was said above, in the first section, that the process of translation is characterized by repeated recursions to the extralinguistic content of messages. However, the process of translation is also a linguistic process and a strict separation of the translation would look as follows: Extralinguistic message Formal correspondence source text target text Formal correspondence The contrastive pair of formal correspondence links forms the base of the triangle of communication by translation and servers as a basis for the establishment of translation equivalence. The translator begins his search for translation equivalence from formal correspondence, and it is only when the identical-meaning formal correspondent is either not available or not able to ensure equivalence that he resorts to formal correspondents with not-quiteidentical meaning or to structural and semantic shifts which destroy formal correspondence altogether. But even in the latter case he makes use of formal correspondence as a check on meaning – to know what he is doing, so to speak. A realistic theory of translation will have to account for the communicative and for the linguistic (in the narrow sense) aspects of the translator’s work. The linguistic aspects are contrastive in nature. Equivalence appears as a product of the contrasting of textually realized formal correspondents in the source and the target language and the communicative realization of the extralinguistic content of the original sender’s message in the target language. Both components are present in the process of translation and together ensure dynamic equivalence which avoids both literalness and paraphrase. References BOLINGER, d., 1966. “Transformulation: Structural Translation,” Acta Linguistica Hafniensia IX, 130-144, CATFORD, J.C., 1965. A Linguistic Theory of Translation (Oxford UP) FILIPOVIĆ, R., 1971. “The Yugoslav Serbo-Croatian – English Project,” in: G. Nickler, ed., Papers in Contrastive Linguistics (Cambridge UP), 107-114. IVIR, V., 1969. “Contrasting via Translation: Formal Correspondence vs. Translation Equivalence,” Yugoslav Serbo-Croatian – English Contrastive Project, Studies 1, 13-25. IVIR, V., 1970 “Remarks on Contrastive Analysis and Translation”, Yugoslav Serbo-Croatian English Contrastive Project, Studies 2, 14-24 JAKOBSON, R., “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation,” in: R.A.Brower, ed., On Transl ation (Cambridge, Mass,: Harvard UP), 232-239. KRZESZOWSKI, T.P., 1971. “Equivalence, Congruence and Deep Structure,” in: G. Nickel, ed., Papers in Contrastive Linguistics (Cambridge UP), 37-48. KRZESZOWSKI, T.P., 1972. “Kontrastive Generative Grammatik, “ in: G. Nickel, ed., Reader zur kontrastiven Linguistik (Athenäum Fischer Verlag: Frankfurt), 75-84. MARTON, W.,1968.“Equivalence and Congruence in Transformational Conrastive Studies,” Studia Anglica Posnaniensia I, 53-62. NIDA, E.A., 1969. “Science of Translation,” Language 45, 483-498. 1977 “The Nature of Dynamic Equivalence in Translating,” Babel XXIII, 99-103. RAABE, H., 1972. “Zum Verhältnis von kontrastiver Grammatik und Űbersetzung,” in: G. Nickel, ed., Reader zur kontrastiven linguistik (Athenäum Fischer Verlag: Frankfurt), 59-74. SPALATIN, l., 1967. “Contrastive Methods,” Studia Romancia et Anglica Zagrabiensia 23, 29-45. STEINER, G., 1975. After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (Olxford UP)