Anxiety_of_Postwar_A..

advertisement

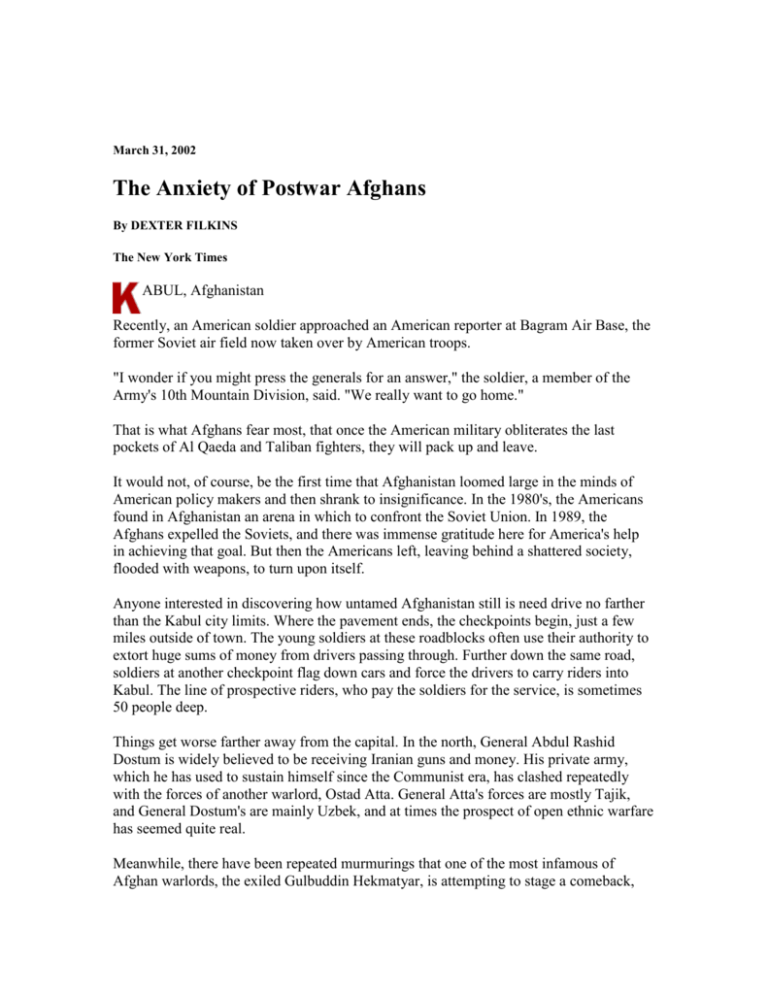

March 31, 2002 The Anxiety of Postwar Afghans By DEXTER FILKINS The New York Times ABUL, Afghanistan Recently, an American soldier approached an American reporter at Bagram Air Base, the former Soviet air field now taken over by American troops. "I wonder if you might press the generals for an answer," the soldier, a member of the Army's 10th Mountain Division, said. "We really want to go home." That is what Afghans fear most, that once the American military obliterates the last pockets of Al Qaeda and Taliban fighters, they will pack up and leave. It would not, of course, be the first time that Afghanistan loomed large in the minds of American policy makers and then shrank to insignificance. In the 1980's, the Americans found in Afghanistan an arena in which to confront the Soviet Union. In 1989, the Afghans expelled the Soviets, and there was immense gratitude here for America's help in achieving that goal. But then the Americans left, leaving behind a shattered society, flooded with weapons, to turn upon itself. Anyone interested in discovering how untamed Afghanistan still is need drive no farther than the Kabul city limits. Where the pavement ends, the checkpoints begin, just a few miles outside of town. The young soldiers at these roadblocks often use their authority to extort huge sums of money from drivers passing through. Further down the same road, soldiers at another checkpoint flag down cars and force the drivers to carry riders into Kabul. The line of prospective riders, who pay the soldiers for the service, is sometimes 50 people deep. Things get worse farther away from the capital. In the north, General Abdul Rashid Dostum is widely believed to be receiving Iranian guns and money. His private army, which he has used to sustain himself since the Communist era, has clashed repeatedly with the forces of another warlord, Ostad Atta. General Atta's forces are mostly Tajik, and General Dostum's are mainly Uzbek, and at times the prospect of open ethnic warfare has seemed quite real. Meanwhile, there have been repeated murmurings that one of the most infamous of Afghan warlords, the exiled Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, is attempting to stage a comeback, possibly with General Dostum's help, possibly with Iran's. Mr. Hekmatyar cut his reputation during the civil war in the 1990's, when his relentless rocketing of Kabul killed tens of thousands of civilians. That such an array of characters might threaten the Afghan government seems, at least in some corners, lost on American policy makers. This month, American officials announced their opposition to an Afghan request to enlarge the 4,500-person international security force now keeping order in Kabul, and expand it to other cities. At a news conference last week, Zalmay Khalilzad, President Bush's envoy to Afghanistan, was asked repeatedly how he expected the Afghan government to maintain order without the help of more international troops. Mr. Khalilzad answered that, in the long run, a national army would be the Afghans' best hope. When he was asked about the short run, Mr. Khalilzad gave a surprising answer: Disputes between local warlords, he suggested, might have to be resolved by American troops on the ground. "We have assets and forces in all these places," he said. "One of the things they do is discourage this sort of thing." The prospect of American military forces intervening in tribal and ethnic conflicts is not exactly what the Americans want, however. The military, in particular, is wary of getting stuck in another Afghan civil war. ON the other hand, Afghans of nearly all stripes might welcome a scaled-back security force, enough to put 100 or so troops in the largest Afghan cities. Despite their well-earned reputation for ferocity, the typical Afghan fighter, whether a warlord's sepoy or a Talib on the run, holds the American military, and American soldiers, in something approaching a state of awe. The prospect of being bombed by a B52 concentrates the mind. But this won't answer the larger question of how to create a stable, unified, Afghan nation. Officials in the Bush administration have said repeatedly that they intend to help Afghanistan find its feet, that they'll be there if the chaos returns, and that the abrupt disengagement of the late 1980's would not repeat itself. But to many Afghans here, the assurances have an increasingly saccharine flavor. This is the same administration, long before the events of Sept. 11, that vowed it would not engage in what it contemptuously referred to as nation building in the more anarchical outposts of the Third World. "The Americans are desperate to achieve their goals here against terrorism, and that is understandable," a senior member of the Afghan interim government said recently. But he expressed concern that Afghanistan's overall instability was being ignored in the concentration on military objectives. "If tensions mount here again," he said, "you will not be able to stop it. It is like a fire in the bushes." For months, Afghan officials, including the chairman of the interim government, Hamid Karzai, urged that the international security force now keeping the peace in Kabul be expanded to other parts of the country while the national army takes shape. Mr. Karzai's fear, which he pressed repeatedly upon the Bush administration, is that without such a force, Afghanistan's demonstrated propensity for chaos might reassert itself, and the Afghan government will be powerless to contain it. THIS month, however, Vice President Dick Cheney, followed by a succession of American officials, said that the United States would oppose expanding the international security force. Some of the countries already supplying troops for the force, including Britain and France, have military commitments elsewhere and are reluctant to provide any more. American leaders said they would instead take the lead in training an Afghan army to replace, and if need be, subdue, the dozens of armed groups that now roam the countryside. The Afghans desperately need a unified national army, no doubt about that. The recent American-led battle against Taliban and Qaeda forces in the Shah-i-Kot Valley illustrated not just that the Afghan government does not control its own territory, but that it is incapable, without American help, of taking on a disciplined fighting force. For the Americans, it would be no small feat to cobble together the Uzbeks, Tajiks, Hazaras and Pashtuns who, for much of the past 13 years, have engaged mainly in slaughtering one another. At some future point, the American thinking goes, an Afghan national army would be able to disarm the warlords, slap down any resurgent Talibs and guard the palace. By so doing, an Afghan army could even serve as an engine to tie this fractious country together. But that moment is a long way off, according to those now training the Afghan army, the British. Assuming all goes well, they say, the first 500 Afghan recruits will reach "initial operational capability" in a year. By American estimates, a 12,000-person force will be ready in September 2003. And therein lies the source of the Afghan angst: that in the end America will commit neither the resources nor the time needed to hold Afghanistan together until it can fend for itself.