Title: Effect of Resource Depression on the Territoriality of the Anna

advertisement

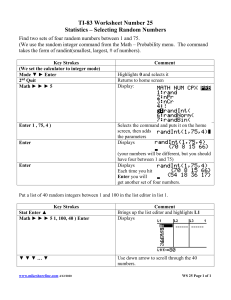

Effect of Artificial Concentrated Feeding Area Resource Depression on the Territoriality of the Anna Hummingbird (Calypte anna) Linda Mahoney and Kathleen Kuechler Department of Biological Sciences Saddleback College, Mission Viejo, Ca 92692 Abstract: Territorial behaviors such as chases and gorget displays are often used by Anna’s hummingbirds to defend their feeding territory. The intensity of such a display is determined by the quality of food resources in said territory, which in turn dictates the amount of energy that can be expended to defend a territory from intruders (Carpenter et al. 1989). This study compared the frequency of high-intensity territorial displays when resource availability was either “superabundant” (this isn’t mentioned until discussion) (Carpenter 1987) or depressed in a resident population of Anna’s hummingbirds whose main food supply was a spatially concentrated locale of artificial feeders. It was hypothesized that the hummingbirds would exhibit a greater frequency of high-intensity territorial displays when they received high-quality resources (high resource availability?) due to increased energy uptake, allowing them to exert more energy defending their feeding territory. It was found that Anna’s hummingbirds exhibited high-intensity territoriality at a frequency of 0.13270.0129(s.e) when receiving high-resource food and 0.11420.02893(s.e) when receiving low-resource food. There was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of high-intensity territoriality under the two conditions (p=0.2883,one-tailed t test). These results were most likely attributed to elements of Carpenter and MacMillan’s 1976 Threshold model as well as Myers et al argument of competition density. Introduction: One consequence of bird evolution is the development of a social organization structure that uses territoriality as one of the primary mechanisms for interspecies and intraspecies interactions (Brown 1969). These interactive dynamics determine individual fitness, with the crux of an individual’s fitness resting on the regulation of their (its, his/her; pronoun needs to match) energy budget (Carpenter et al. 1989). In other words (change transition “In order to achieve maximum fitness level” or something similar), individuals must balance their expenditure of energy with their ability to acquire energy. Territorializing areas with sufficient amounts of nourishment ensures that individuals obtain the energy they need to maximize fitness. However, these behaviors most often occur when the fitness benefits outweigh the energy costs (Brown 1964). Male hummingbirds vigorously territorialize feeding areas, particularly with regards to other males, encompassing easy access to abundant high-quality food sources with the expectation that a female will enter their territory seeking a stable nesting site (Sibley 2001) (this sentence seems disjointed). Female hummingbirds additionally exhibit feeding territorial behaviors, but primarily in the resource obtainment for and defense of their nesting site (Sibley 2001) (awkward at the end of sentence; maybe switch around “resource obtainment” and “defense”). Territoriality displays can either be an energetically low-cost or high-cost expenditure, whereby the hummingbird exerts either a minimal or maximal amount of energy to perform their (match pronoun to “the hummingbird”) intended behavior. According to Brown’s 1969 and Ewald and Carpenter’s 1978 studies, territorial exhibits such as attacking or long chases are considered (a) high energy-cost expenditures as the defending bird literally chases an 1 (page numbers) invading bird away from their (match pronoun) territory. In short chases, or those in which the defender needs not (or “does not need to)exit its territory before successfully driving an intruder away, threats or gorget displays and vocalizations are all considered low-cost expenditures. In order to ensure that enough energy resources are available to meet their energy needs, individuals defend high-quality food sources, or those with increased sucrose concentrations, with a greater frequency of high-cost displays than areas with food sources containing lower sucrose concentrations (This sentence seems wordy. Try breaking it into two sentences. Also, what concentrations are considered “high-quality” or “low-quality?” It’s very ambiguous)(Brown 1964; Powers 1987; Ewald and Carpenter 1978). As the quality of food sources decreases, hummingbirds invest less energy into their territoriality displays, thus exhibiting a greater low-cost to high-cost behavioral frequency (Ewald and Orians 1983; Ewald and Carpenter 1978). According to previous studies, whether a hummingbird will use high-cost or low-cost territoriality behaviors is predicated upon the availability of high-quality food sources (Ewald and Carpenter 1978; Powers 1987; Ewald and Orians 1983). The studies previously discussed focus on hummingbirds obtaining nourishment from both natural and artificial sources, such as bird feeders, in which resources are ostensibly scattered in a random pattern, as no mentions are made pertaining to the spatial distribution of resources. In an effort to differentiate those feeding area distributions from the arrangement which existed in this study, previous researchers have termed areas with mixed source, widely spaced feeding areas “natural/artificial decentralized feeding areas,” or NADFA, and areas with a centrally located and artificial source as “artificial concentrated feeding areas”, or ACFA. In this study, researchers are interested in studying whether the frequency of high-cost territorial displays and resource availability (This is the first time resource availability is specifically mentioned and it is the independent variable in your experiment. In the previous paragraph, you expand a lot on resource quality rather than resource availability. Based on your definition of resource quality and how you actually controlled for resource availability in the methods, it appears that they are two separate factors that can affect territorial behavior. I think it might be beneficial to provide greater background on resource availability (specifically resource depression). You allude to other previous studies. How do they define resource availability? Do they define what is high/low?) so often studied in NADFA also exists in ACFA with a dense population of feeding hummingbirds. Though the density of hummingbirds and space limitations differ from previous studies, the type of behaviors displayed by individuals can only exist as far as their energy budget, thus it is hypothesized that the same relationship between high-resources and a greater frequency of high-intensity behaviors will be exhibited. Method and Materials: This study was conducted at a residential three-and-a-half acre avocado grove located in Bonsall, CA, for a duration of four days during mid-March 2010. The daytime temperatures averaged between 22.8-23.9oC and wind speeds averaged 3.5mph. The hummingbird feeders were located on the residences’ back porch, facing the lower half of the avocado grove. Based on years of observations and the abundance of occupied and abandoned nests discovered on the premises by grove owners, the home range (Brown and Orians 1970) of the population of Anna’s hummingbirds studied remains within the grove’s perimeter and possibly within adjacent lots. These “resident” hummingbirds have been provided with nine large commercial feeders containing a consistent supply of an approximately 1.16M sucrose solution for the past six years. Each feeder has seven feeding stations resembling a red and yellow flower and has the capacity 2 (page numbers) to hold 0.960L of solution. While these resident hummingbirds are not tagged and no official counts have been made, it is estimated by grove owners that the Anna’s population numbers between 100-200 individuals, depending on the season. Other species of hummingbirds, such as Rufous, Black-Chinned, and Calliope, have additionally been observed residing on the grove but only in seasonal durations. Researchers of this study took great care in assuring that videotaping was completed prior to the migrational introduction of non-Anna’s species. The residence’s partially enclosed back porch uses five large evenly spaced pillars for support; two outside pillars and three middle pillars. Attached to the trim between each middle pillar are three hooks for the suspension hummingbird feeders. Nine total feeders are supported by this arrangement. As the resident hummingbirds are accustomed to nine feeders (or 63 feeding stations) at any given time, researchers considered this arrangement “high-resource” availability. When only three feeders were provided, a 66% reduction in resources, it was considered “low-resource” availability. Maintaining a consistent sucrose content for each day of the study, the researchers designated the first and third day of the study as high-resource and the second and fourth day as low-resource. The three? spaces immediately between the middle pillars were videotaped for 40 minutes each day (simultaneously? At different times?) resulting in a total of eight hours of footage: four hours of high-resource footage and four hours of low-resource footage. Afterwards the footage was analyzed and each incident of territoriality exhibited next to a feeder quantified and categorized as either a high-intensity or low-intensity display based on the behavioral descriptions of previous studies (Ewald and Orians 1982; Ewald and Carpenter 1978; Brown 1969). According to Brown and Orians 1970’s study, a territory is defined as “…a fixed area, which may change slightly over a period of time, [in which] acts of territorial defense by the possessors, which evoke escape and avoidance in rivals so that…the area becomes an exclusive area with respect to rivals.” The intent of this study was to focus on the territorial displays exhibited strictly at the ACFA, therefore researchers did not examine the territorial spatial distributions of areas outside the ACFA’s perimeter. Thus, researchers defined the area surrounding one feeder as a territory (how large was this area?), in accordance with the above mentioned description, based on observations that the hummingbirds will claim and defend one feeder at a time. For purposes of quantifying low-and-high-intensity chase occurrences, researchers designed the following: (1) low-intensity chases were those which remained within the scope of the camera lens, since a defending hummingbird needs only chase an intruding hummingbird a relatively short distance in order to ensure the invader leaves the territory; and (2) high-intensity chases were considered those which continued beyond the scope of the camera lens, as more energy was needed by defenders to chase intruders the longer distance. Gorget displays, typically the first territorial behavior exhibited by hummingbirds before increasing the severity of their warnings (Sibley 2001), and consequently the associated energy allocation, are distinctive enough low-cost behaviors that researchers needed only to use conventional descriptions in order to recognize and quantify occurrences. According to Ewald and Orians 1982 study, gorget displays are “an energetically inexpensive method of defense in which the owner moves its head from side to side while facing the intruder.” Males additionally flash the fuchsia colored iridescent feathers on their crowns to signal a warning to intruders (Sibley 2001). While vocalizations, or announcement, are another significant and frequently used (this part seemed to be a little repetitive so I crossed out first part) low-cost territorial behavior, due to the density of hummingbirds studied it was improbable to accurately determine which hummingbird vocalized 3 (page numbers) a specific chirp recorded on video. For that matter, it would have been improbable to accurately assign chirps if the data had been collected in situ, because of the nearly non-stop activity occurring around each of the nine feeders. Thus, researchers eliminated the quantification of vocalizations based on the fact that most often vocalizations accompany gorget displays and/or chases (Sibley 2001). The data collected quantified the number of high-intensity chases and attacks, and the number of low-intensity chases and gorget displays exhibited per day. These numbers were then compared as a frequency of high-intensity displays exhibited per low-intensity display exhibited. The resulting frequencies for high-resource and low-resource allocation were then accessed using a one-tailed t-test to determine if any statistical significance difference resulted. Results: A total of eight hours of video was taken over the course of four days. Each forty-minute recording segment was defined as one section with three sections recorded per day. As the video was analyzed, the number of high-intensity and low-intensity territorial displays were recorded for each section, as seen below in (Table 1). Then the frequencies of high-intensity displays were calculated for each section by dividing the number of high-intensity displays by the total number of territorial displays. (To be honest, I don’t think you need Table 1 at all. Figure 1 and Figure 2 sum up this information nicely and more directly. And you would include how exactly the frequencies were calculated in the methods section) Table 1. Raw data of high-and-low-intensity displays on either high-resource days or low-resource days and calculated frequencies of high-intensity displays. High-Resource Section 1 2 3 4 5 6 High-Intensity Display 14 3 23 7 6 11 Low-Intensity Display 113 31 119 34 6 11 Frequency of High-Intensity Display 0.1102 0.0882 0.1620 0.1707 0.1224 0.1429 Low-Intensity Display 58 31 23 Frequency of High-Intensity Display 0.0492 0.0606 0.0417 Low-Resource Section 1 2 3 High-Intensity Display 3 2 1 4 11 47 0.1897 5 6 18 13 79 69 0.1856 0.1585 From the calculated frequencies, a one-tailed t test was performed to see if the highresource days exhibited a higher frequency of high-intensity territorial displays than the lowresource days. After the first two days of video were analyzed, it appeared that the data would be 4 (page numbers) Frequency of High Intensity Displays statistically significant and support the hypothesis; however, after looking at the data as a whole over the four days, the results were not as clear-cut. As seen in Figure 1, Anna hummingbirds exhibited high-intensity territoriality at a frequency of 0.13270.0129(s.e) when receiving highresource food and 0.11420.02893(s.e) when receiving low-resource food. There was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of high-intensity territoriality under the two conditions (p=0.2883, one-tailed t test). 0.2 0.18 0.16 0.14 0.12 0.1 0.08 0.06 0.04 0.02 0 High Resource Low Resource Figure 1. Average frequency of high-intensity territorial displays for Anna hummingbirds receiving either a high-resource or a low-resource food supply. Hummingbirds exhibited high-intensity territoriality at a frequency of 0.13270.0129(s.e) when receiving high-resource food and 0.11420.02893(s.e) when receiving low-resource food. There was no statistically significant difference in the frequency of highintensity territoriality under the two conditions (p=0.2883, one-tailed t test). Researchers then compared the number of territorial displays on each territory to see if there would be any statistical difference in the total number of displays. The video of the highresource days was reanalyzed, recording only territorial displays that occurred around a one feeder territory. The resulting data is displayed in Figure 2. When receiving high-resource food, hummingbirds displayed a total of 18 high-intensity and 121 low-intensity territorial behaviors. When receiving low-resource food, they displayed a total of 43 high-intensity and 307 lowintensity territorial behaviors (Figure 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the number of territorial displays between high-resource and low-resource food supplies (p=0.4980, chi-square test). 5 (page numbers) 350 Number of Territorial Displays 300 250 200 High Intensity Low Intensity 150 100 50 0 High Resource Low Resource Figure 2. Total number of high-intensity and low-intensity displays per feeder territory for Anna hummingbirds receiving high-resource food or low-resource food. When receiving high-resource food, hummingbirds displayed a total of 18 high-intensity and 121 low-intensity territorial behaviors. When receiving low-resource food, they displayed a total of 43 high-intensity and 307 low-intensity territorial behaviors. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of territorial displays between high-resource and low-resource food supplies (p=0.4980, chi-square test). Discussion: The results of this study show that the relationship between resource depression and behavioral displays are more complex at ACFA than researchers initially imagined. Yet, as with many prior studies focusing on energy budgets and behavioral displays at NADFA, such as Eberhard and Ewald’s 1994, Kodric-Brown and Brown’s 1978, and Ewald and Carpenter’s 1976 studies, this relationship is often complicated by net energy budgets. Comparison of behavioral data obtained by the first set of high-resource versus lowresource allocation days was consistent with the hypothesis; a greater frequency of high-intensity displays were evident on high-resource days than on low-resource days. However, when comparing the total number of frequencies for all four days, no statistical difference occurred between the high and low-resource conditions. Though this result could have simply been an aberration in data, researchers believe that it is more likely that the combination of resource “superabundance’ (Carpenter 1987) and the sheer density of hummingbirds contributed to a climate of such intense and persistent competition that any potential energy gain by feeder exclusivity was outweighed by the energy requirements necessary for defense. Carpenter and MacMillen’s 1976 study focused on the effects of territoriality and resource depression on the Hawaiian Honeycreeper. Because the study found Hawaiian Honeycreepers only exhibited territoriality some of the time, the model related territoriality to regional food productivity. The authors argued that territoriality should essentially disappear when (1) energy resources drop to the “lower threshold” or the point “below a certain level of food productivity [in] a bird’s feeding area…” and when (2) energy resources climb above the “upper threshold” or the point at which there is a “higher level of food productivity” (Carpenter and MacMillen 1976). This cessation of territoriality, they explain, is due to the energy 6 (page numbers) expenditure costs versus energy gain benefits of defending concentrated food supplies. In other words, the energy obtained from food sources without having to defend the territory is greater than their total daily energy expenditure requirement (aP > E). With regards to this study, the superabundance of energy allocated on a daily basis, prior to the commencement of this experiment, has supplied the resident Anna’s population with resources above the upper threshold for approximately six years. However, based on Figure 2, it appears that the lowresource allocations were within the lower to upper threshold limits as the number of territorial displays increased compared to the superabundant availability. In contrast, Myer’s et al 1981 study claimed the decrease in territoriality around superabundant food sources is caused by excessive competition, not necessarily threshold driven. This argument might also apply to the Anna’s studied in this experiment: as the density of competitors increased, territorial displays not only lost their effectiveness but too much energy was required to drive off all intruders. The loss of effectiveness and necessary energy expenditures could have tempered the ratio of high-intensity-to-low-intensity territorial dynamics between the birds, as the years of intense daily competition for unlimited supplies might have, at the risk of anthropomorphizing hummingbird learning abilities, “taught” them or “shown” them that no net benefits resulted from territorializing unlimited resources. For instance, territoriality displays were still quite prevalent throughout the eight hours of footage, however only high-andlow-intensity chasing was, as far as researchers could determine, the most effective method for defenders to protect their territory from invaders. Gorget displays were the overwhelmingly most common behavior exhibited, yet only 12 instances of such displays were effective enough to drive away an intruder. Otherwise most hummingbirds simply ignored each others’ warning and fed regardless. Potential defenders more often did not pursue invaders and simply began to feed without further aggression. With such competitive density, it could be argued that the invading hummingbirds were not intimidated by simple low-cost displays, yet defending hummingbirds did not pursue more energetically demanding displays because the benefits to exclusivity did not outweigh the costs associated with such rigorous and constant defense. Other studies, such as Ewald and Carpenter’s 1978 and Ewald and Orian’s 1983 studies, contained numerous feeders and a superabundant food supply, yet the studied hummingbirds still exhibited frequent high-intensity territorial displays. Dr. Carpenter, in her 1987 paper, discussed the possibility that the territorial defenses were still utilized by those hummingbirds because though food productivity was abundant in the area of study, regionally there was a food productivity limitation driving the hummingbirds to defend high quality food sources. (It is important to note that researchers could find no further definition of what constituted a “region” by which to understand where the boundaries of regional food productivity lie. Thus, researchers interpreted the definition as the hummingbird population’s home range, for ease of comparison.) However, in the area of study for this experiment, the three-and-a-half acre grove is situated in an agricultural setting with an approximate three square mile radius of nearly uninterrupted flowering citrus and avocado trees. If the hummingbirds seek nourishment outside of the ACFA, the same superabundant food productivity environment exists year-round well beyond their home range. As with any behavioral study, further data could help to resolve or explain inconsistencies between results. A total of two days of resource depression might not have been a sufficient length of time to capture behavioral differences considering the complex social dynamics and energy requirements of hummingbirds. In addition, researchers could have lowered the availability and quality of food sources in accordance to Carpenter and MacMillan’s 7 (page numbers) lower threshold. Unfortunately, researchers believe they did not sufficiently depress food supply per individual in order to achieve this lower threshold. However, because energy budgets were not the main focus of this study, a per calorie comparison was not calculated. Further research on the effects of ACFA resource depression and territoriality should include more hours of observation, a threshold quantification, and a low-resource acclimation period of at least one week prior to data collection in order to ease the transition of superabundance to resource depression. (Very good discussion!!) Literature Cited: Brown, Jerram L., 1969. Territorial Behavior and Population Regulation in Birds. The Wilson Bulletin. 81(3): 293-329. Brown, Jerram L., Orians, Gordon H., 1970. Spacing Patterns in Mobile Animals. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1: 239-262. Carpenter F. Lynn, MacMillen R. E., 1976. Threshold Model of Feeding Territoriality and Test with a Hawaiian Honeycreeper. Science. 194: 639-642. Carpenter, F. Lynn, 1987. Food Abundance and Territoriality: To Defend or Not to Defend?, American Zoologist. 27 (2): 387-399. Carpenter, F. Lynn, Hixon, A., Paton, D. C., 1989. Regulating Body Mass Changes to Fitness in Hummingbirds. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 70: 77 Eberhard, Jessica R., Ewald, Paul W., 1994. Food Availability, Intrusion Pressure and Territory Size: An Experimental Study of Anna’s Hummingbirds (Calypte anna). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 34 (1): 11-18. Ewald, Paul W., Carpenter, F. Lynn, 1978. Territorial Responses to Energy Manipulations in the Anna Hummingbird. Oecologia. 31(3): 277-292. Ewald, Paul W., Orians, Gordon H., 1983. Effects of Resource Depression on Use of Inexpensive and Escalated Aggressive Behavior: Experimental Tests Using Anna Hummingbirds. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 12: 95-101. Kodric-Brown, A., and Brown, J.H., 1978. Influence of Economics, Interspecific Competition, and Sexual Dimorphism on Territoriality of Migrant Rufous Hummingbirds. Ecology. 59: 285-296. Myers, J. P., Connors, P.G., Pitelka, F. A., 1979. Territory Size in the Wintering Sanderling: The Effect of Prey Abundance and Intruder Density. The Auk. 96: 551-556. Powers, Donald R., 1987. Effects of Variation in Food Quality on the Breeding Territoriality of the Male Anna’s Hummingbird. The Condor. 89(1): 103-111. 8 (page numbers) Sibley, David A., 2001. The Sibley Guide to Bird Life and Behavior. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York. Stiles, F. Gary., 1982. Aggressive and Courtship Displays of the Male Anna’s Hummingbird. The Condor. 84(2): 208-225. 9 (page numbers) Review Form Department of Biological Sciences Saddleback College, Mission Viejo, CA 92692 Author (s): Linda Mahoney and Kathleen Kuechler Title: Effect of Artificial Concentrated Feeding Area Resource Depression on the Territoriality of the Anna Hummingbird (Calypte anna) Summary Summarize the paper succinctly and dispassionately. Do not criticize here, just show that you understood the paper. This paper aimed to look at the affect of resource depression on the frequency of high-intensity territorial displays and low-intensity territorial displays in Anna’s hummingbirds (Calypte anna). They hypothesized that there would be an increase in high-intensity territorial displays as resource availability increased. Observations took place at an avocado grove over a period of four days. A total of eight hours of video were taken, two hours each day. Days one and three were designated “high-resource” days and days two and four were “low-resource” days. Based on the video footage, counts were made of the various high-intensity displays (long chases) and low-intensity displays (short chases, gorget displays). The frequencies of high-intensity displays were calculated and a one-tailed t-test was run to determine any statistical significance between the frequency of high-intensity displays with high-resource and lowresource availability. Also, a chi-square test was run to determine statistical significance between the total number of high-and-low-intensity territorial displays and resource availability. Neither test showed any statistically significant difference (p=02883, one-tailed t-test; p=0.4980 chi-squared test). Previous studies supplied potential explanations for the lack of significance. One concept discussed was the idea of “superabundance” combined with the total number of hummingbirds present. Also, the lack of territorial behaviors General Comments Generally explain the paper’s strengths and weaknesses and whether they are serious, or important to our current state of knowledge. Overall, this paper was written very well and provided a lot of background information. However, it did get wordy at times and it seemed like certain sentences could have been condensed and more direct. One big problem that I had (mainly in the introduction and a little in the abstract) was the idea of resource quality versus resource availability. The introduction is set up geared toward resource quality and a lot of studies are provided that define what it is. However, the researchers ended up looking at resource availability instead which is not given as much attention until the very end of the introduction and somewhat in the methods. I felt like the paper was being set up to look at quality (adjusting sugar concentrations) and I became a little confused when their hypothesis involved resource availability (specifically resource depression). I feel they could have expanded more on resource availability and not so much on resource quality. Also, in the results, I think that Table 1 is unnecessary and that the data is more directly provided in Figures 1 and 2. I have to say that I found the discussion to be extremely good. I did not say too much about it because I felt it did a great job of discussing their results and the potential reasons that may have contributed to their lack of significant. They did this while incorporating other related studies which further supported their argument. 10(page numbers) Technical Criticism Review technical issues, organization and clarity. Provide a table of typographical errors, grammatical errors, and minor textual problems. It's not the reviewer's job to copy Edit the paper, mark the manuscript. This paper was a final version Typographical errors Grammatical errors Minor textual problems This paper was a rough draft --In the beginning, not all of the pronouns matched up with the nouns. Page numbers missing I felt that this paper was very organized and well thought out. There were no spelling errors and extremely minor grammatical errors. Recommendation This paper should be published as is This paper should be published with revision This paper should not be published Signature:______________________________________ Date:__________________ Read more about Peer Review in the biological sciences at: http://www.councilscienceeditors.org/services/draft_approved.cfm#Paragraphsix I read the information from the site listed above: Initials 11(page numbers)