Waterlands - Building on flood plains is asking for trouble

advertisement

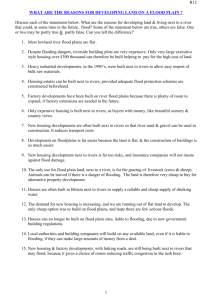

Waterlands - Building on flood plains is asking for trouble (This article first appeared in the Times on the 14th of October 2005. ) There was plenty of warning. The weathermen, police and environmental agencies were monitoring the stormclouds, watching river levels and alerting householders that danger was coming. Yet when the floods swept through the market towns of the South East, hundreds of people were caught unawares, their houses engulfed by a tide of swirling brown water. The flooding is the worst for decades. Damage is estimated at well over £100 million, and with more rain forecast and rivers still rising in the most prosperous and densely populated part of Britain, this autumn could prove one of the most costly for years. Floods and extreme weather now seem to be a fact of life. In the past two years more than 30 floods have inundated low-lying areas across a swath of Britain, causing millions of pounds' worth of damage to property, livestock and historic towns and claiming dozens of lives. In 1947 only 790 properties in Maidenhead were at risk; by 1990 the number had grown to 2,300. The Environment Agency has given a warning that more than five million people live in areas prone to flooding, and insurance companies are redrawing the boundaries to exclude cover for areas at risk. Nature is partly to blame. Global warming is a fact, and the thermal expansion of oceans is pushing up tides farther than before. Sea levels around parts of Britain have risen by about six inches in the past 80 years. In addition, the British Isles are slowly tilting into the sea, with southern England dipping about four millimetres a year. Rainfall has become more erratic, so that some areas now receive an entire month's supply of rain in one day. High tides are pushed up by stronger winter winds; the Thames Barrier has already saved London from at least 30 devastating floods since it was built. Man, however, is far more to blame than nature. In the great postwar building booms, millions of houses have been built on ancient flood plains. Indeed, houses close to rivers or with fine views over flat low land often command premium prices. Noting could be stupider or more likely to lead to trouble. Flood plains are nature's way of controlling rivers that burst their banks. They are huge overflow areas where acres of water can drain slowly into the ground. Rich, fertile and damp, they are not suitable for housing. Indeed, even on sloping ground the very foundations act as dams, causing water levels to build up. Attempts to regulate rivers have also made things worse. Many have been narrowed with concrete embankments, constricting and accelerating the flow; those that meandered have been straightened, making them run faster when they are swollen. Some rivers have been diverted through town centres, others hemmed in by roads, embankments and gravel pits. Meanwhile, the water table under most towns is rising inexorably as industry stops pumping ground water. Time and time again this foolish engineering has led to disaster, most spectacularly when the Mississippi burst its concrete banks seven year ago, inundating homes and towns on the plains for hundreds of square miles. Yet half the 90,000 British planning applications each year are for building on land at risk of flooding. As the Environment Agency now suggests, they should be routinely refused. The insurance market will make people warier of where they live. So will repeated pictures of disaster. Only nature can determine how much rain falls on our land. But only man can be so foolish as to ignore the law that water finds it level.