FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATE EXPOSURE

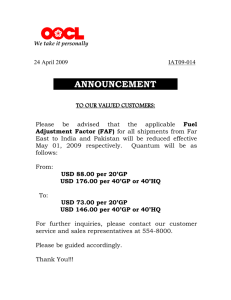

advertisement

FOREIGN EXCHANGE RATE EXPOSURE The fluctuations in exchange rates subject firms operating in the international environment to as many as three types of exposure to exchange rate risk: 1. Transaction exposure 2. Translation exposure 3. Economic exposure The first of these, transaction exposure, is the risk of gains or losses that occurs when a firm engages in commercial transactions in which the currency of the transaction is foreign to the firm; i.e., it is denominated in a foreign currency. This is the type of exchange rate risk that we have looked at the various ways of managing via futures, forward contracts, options and money market hedges. Currency Swap Another means of hedging transaction exposure is through what is known as a currency swap. With a currency swap, two companies can agree to exchanging set amounts of currency at fixed rates of exchange. Of course, the fixed rates of exchange will be set to reflect interest rate differentials (Interest Rate Parity). Swaps help a company faced with possible foreign exchange restrictions and a lack of forward markets. Exposure Netting Exposure netting refers to the ability to use opposite exposures to reduce the amount of risk that a firm is faced with. Just as we can create opposite risks with a futures contract or options, it is sometimes possible to create one transaction exposure in order to offset another. For example, if a U.S. firm has a payable to a British company in pounds (short position), it may want to invoice a receivable in pounds (long position) in order to create an offset. The company could then hedge only the net long (short) position and, thus, reduce its hedging costs. Many multinationals actually have a separate subsidiary that manages the worldwide exposure through netting, known as a reinvoice center. Translation Exposure A firm which has subsidiaries and assets in another country is subject to translation exposure. Translation exposure results as a consequence of the fact that a parent company must consolidate all of the operations of its subsidiaries into its own financial statements. Since a foreign subsidiary’s assets are carried on its books in a foreign currency, it is necessary to convert the foreign values into domestic currency for combining with the parent’s assets. Fluctuating exchange rates results in gains and losses occurring during the translation process. Since this type of exposure is related to balance sheet assets and liabilities, it is often referred to as accounting exposure. The primary issue related to the translation of foreign asset values has to do with whether the proper exchange rate to use is the current rate of exchange or the historic rate of exchange that existed at the time that an asset was acquired. In order to see the possible gains and losses that can occur, let’s consider the following: A U.S. company has a Mexican subsidiary that buys an asset for 12 million pesos in 20x1 when the exchange rate is 12 pesos per USD. Over the following year, inflation in Mexico is 50% while in the U.S. it is 0%. Of course, if purchasing power parity holds, then the exchange rate in one year should be 18 pesos per dollar. If we use historical cost accounting, the asset will have a value of 12 million pesos on the Mexican subsidiary’s books. Translating this at the current exchange rate of 18 pesos/USD yields a US dollar value of 12,000,000 pesos USD 666,667 18 pesos/USD If we translate the historical cost of 12 million pesos at the historical exchange rate at the time of acquisition of 12 pesos/USD we get a US dollar value of 12,000,000 pesos USD 1,000,000 12 pesos/USD Thus, the correct value would be to use the historical exchange rate when the books are kept on an historical cost basis. On the other hand, Mexico is a country that utilizes an inflation-adjusted (or current) accounting system where assets are indexed for inflation. Thus, the Mexican subsidiary would carry the asset on the books at 18 million pesos (12 million pesos * (1+50%) = 18 million pesos). Translating this using the current exchange rate of 18 pesos/USD yields 18,000,000 pesos USD 1,000,000 18 pesos/USD If the historical exchange rate were used, we would obtain the following value: 18,000,000 pesos USD 1,500,000 12 pesos/USD For the proper translation of value, we should either use the historic exchange rate with historical cost accounting or the current exchange rate with current accounting practices. For a foreign currency that has depreciated, we get the following general results (an appreciating currency would yield the opposite results): Accounting Valuation Method Translation Exchange Rate Historic (Book Value) Current (Market Value) Historic No Change Increased Value Current Decreased Value No Change In 1981, FASB 52 set the rules for U.S. GAAP accounting in which it stated that all asset and liability accounts must be translated at the current rate of exchange. Equity accounts are translated at historical rates of exchange. A separate account, ”Equity Adjustment from Translation”, is used to reflect translation gains and losses. The only exception to this is for assets in countries experiencing hyperinflation which is defined as cumulative inflation greater than 100% over a three-year period. In that case, historical exchange rates are allowed for nonmonetary items (inventory/cost of goods sold, plant & equipment/depreciation). In any event, translation exposure is not a real gain or loss in terms of making or losing money. The value of the asset is the value of the asset. The gain or loss results simply from translating from one currency to another. In that sense, one should not really worry about translation exposure (except to the extent that there is a perceived gain or loss from unsophisticated users of the financial statements). Economic Exposure While transaction exposure is an economic exposure in the sense that a real gain or loss can result (unlike translation exposure which is just an accounting gain or loss), the use of the term in this context is in reference to the risk associated with revenues, costs and demand for goods as foreign exchange rates fluctuate. Sometimes economic exposure is called “operating exposure” since it refers to the risk to operations. An example would be a devaluation of a foreign currency which would make your product relatively more expensive. Thus, it would be less competitive in the foreign country (as well as domestically), resulting in lower sales and lower profits. How can a company hedge against economic exposure? There is no perfect hedge, but there are actions that a company can take to help offset the risks over the longer period of time. Production Management – Product sourcing: Diversify your source of materials. If you are producing in a foreign country that experiences a devaluation, then some of the loss of sales and profits from your products becoming relatively more expensive is offset by the fact that some of your costs have become less expensive since they are now bought from a country with a weaker currency Shifting production: As sales drop due to a currency becoming more expensive, you can shift production to countries where a weaker currency results in lower costs, again protecting your profit margin even though sales will decline. Marketing Management – Geographic diversification: If sales weaken in one country, they may increase in another due to a change in currency values Market segmentation: High-end (luxury) segment or low-end (economy) Market share versus profit margin Product differentiation: helps make product less sensitive to price changes Financial Management – Arrange financing so that a decrease in sales from a weaker currency is offset by cheaper debt servicing costs