Andrew Carnegie: - University of Hawaii

advertisement

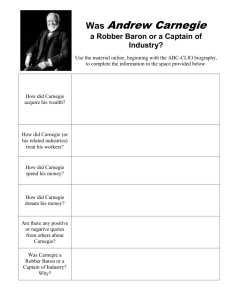

Andrew Carnegie: “Patron Saint of U.S. Libraries” LIS 610 – Intro to Library & Information Science Dr. Noriko Asato March 6, 2008 Table of Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 A Biography of Andrew Carnegie .................................................................................. 5 Carnegie’s Library Philanthropy .................................................................................. 10 Andrew Carnegie and the Library of Hawaii ................................................................ 16 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 23 2 Introduction To some he is known as one of the greatest examples of the power of the American dream, a poor immigrant who pulled himself up by the bootstraps in order to become one of the wealthiest individuals in U.S. history. To others he is viewed as a classy criminal, a wealthy robber-baron who made his fortune on the backs of his downtrodden workers. There is truth behind both viewpoints, certainly, but then there is a third category that fewer individuals know about, but that is equally indisputable. To these few, he is known as the “Patron Saint of U.S. Libraries,” a philanthropist who provided vast sums of his accumulated wealth to the development of public libraries throughout America. The man spoken of here is none other than Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish immigrant who in time became a wealthy steel tycoon and supporter of public libraries across the country. Like him or not, Carnegie is regarded by many in the field as one of the most important individuals in American library history. His generous grants helped to establish hundreds of buildings that provided free library services to the public, and the attention that resulted from his actions brought the issue of library development to the forefront of American minds everywhere. This paper, jointly authored by three students in the Library and Information Science Program at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, is intended to provide information on Andrew Carnegie and the critical role he played in the development of public libraries in the United States. The first question to be answered, of course, is “Who exactly was Andrew Carnegie?” In the first section of this document, __________ ___ provides a brief biography of Carnegie’s life and achievements. Information on how 3 Carnegie came to America, how he climbed the ranks in various businesses, how he amassed his vast fortune, and other topics that set the stage for his eventual philanthropy can be found here. Despite his great wealth, Andrew Carnegie was not one to give money away frivolously. Before he approved a grant for the development of a new library, there were certain standards that he required be met by the requesting community. In the second section, ___________ examines the finer points of Carnegie’s philanthropy. The rationale behind Carnegie’s generosity, his standards for grant provision, and reactions to his patronage are among the topics covered here. Though he was often situated in the “economic capital” of America, New York City, Carnegie’s reach was long, extending far across the county. Even citizens of the remote 50th state, Hawaii, have benefited from Carnegie’s philanthropy. The modern day Hawaii State Library, located in the capitol of Honolulu, was originally made possible by a grant from the steel tycoon. In the third and final section, ______________ examines the topic of Carnegie and library development at the local level, reporting on the history and process by which the people of Hawaii were able to obtain Carnegie’s patronage for a public library of their own. 4 A Biography of Andrew Carnegie Andrew Carnegie was born in 1835 in Dunfermline, Scotland (Husband, 91) and died in Lenox, Massachusetts in 1919 (Husband, 91). Between those two years he had both amassed and spent an unbelievable amount of wealth. He died after living a life of a businessman and a philanthropist. Along the way he met such famous and powerful people as Woodrow Wilson, William Gladstone, Matthew Arnold, and Herbert Spencer. The Carnegie family at the time was theologically liberal; Will Carnegie, Andrew's father, walked out of his Presbyterian church one day over a dispute with the Calvinist creed (Carnegie, 22). They later showed Unitarian and Swedenborgian sympathies (Carnegie, 21). Andrew himself is said to have been less than God-fearing (Livesay, 18). Politically, the family was involved in the Chartist movement in Scotland (Livesay, 7); in his autobiography Andrew recounts how as a child he echoed his family's liberal/radical sentiments (Carnegie, 8), and 'Death to privilege' was a motto he formed early in his youth (Carnegie, 11). As a child, Andrew Carnegie was infused with a strong Scottish nationalism, learning about folk heroes such as William Wallace and Robert the Bruce. When he was scared or tempted to give up, he would ask himself what Wallace would have done, and of course Wallace would have pressed on in any situation (Carnegie, 15). Carnegie claims to have enjoyed the relatively little schooling he received (from ages eight to thirteen) (Carnegie, 13). Later, Carnegie would develop a love of Shakespeare after reading his works in one Colonel James Anderson's library in the United States (Carnegie, 44). 5 Dunfermline in those days was a weaving town and had been for centuries (Husband, 91). Andrew Carnegie's father had been a weaver and even bought three handoperated looms in expectation of increasing business. However, the Industrial Revolution and the change in technology that comprised it caused the weaving business to change in a fundamental way: hand-operated looms were now obsolete, and Will Carnegie's technical expertise was no longer such an advantage in the business. Economic conditions worsened until it became clear that the Carnegies could no longer stay in Dunfermline. They planned to move to the United States in search of better economic opportunities. Eventually, the Carnegie family made enough money to move to Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, by way of New York, Buffalo, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh (Carnegie, 27 & Husband, 93). The family then consisted of a father (Will), mother (Margaret), and two sons (Andrew being the older and Tom being about eight years younger); Andrew was thirteen years old when they moved (Carnegie, 24). While Will Carnegie, a product of the world before the Industrial Revolution, sank into despair and misfortune (at least according to one source) (Livesay, 17), Andrew was young enough to straddle the two eras of economic history (Livesay, 13). He moved up the ranks, finding better opportunities at a relatively early age. Will had at first tried to sell his hand-loom-made textiles door-to-door, but, as Andrew Carnegie writes in his autobiography, 'The returns were meager in the extreme” (Carnegie, 29). Soon, Will had to give up the textile business and found work in a cotton factory belonging to one Mr. Blackstock; Andrew Carnegie was also given a job there as a bobbin boy at the same 6 time, for a weekly pay of $1.20 (Carnegie, 33). 'It was a hard life', as he put it in his autobiography (Carnegie, 33). Andrew Carnegie soon changed jobs when John Hay employed him, at a weekly pay of two dollars, at his bobbins factory as an engine/boiler operator (Carnegie, 33). Although it paid more than his previous job, Carnegie apparently also hated it more (Carnegie, 34), but later he changed duties in the factory, when Hay put Carnegie to bookkeeping and other clerical tasks (Carnegie, 34). However, he also had to put the bobbins in vats of oil, which caused problems with his stomach (Carnegie, 34). Carnegie in his autobiography does not say whether it was better doing the clerical tasks or the engine operations, he in any case states that his 'service with Mr. Hay was a distinct advance upon the cotton factory' (Carnegie, 35). In 1850 Carnegie was employed as a messenger by David Brooks at the telegraph office at a weekly rate of $2.50 (Carnegie, 36); Livesay identifies it as the O'Reilly Telegraph Company (Livesay, 18). It is described in Carnegie's autobiography as his 'first real start in life' (Carnegie, 37). After a year Carnegie was selected by Colonel John P. Glass to look after his office while Glass became more involved in politics; for this Carnegie was paid a monthly wage of $13.50 (Carnegie, 52). After taking a telegraph for an absent operator, Carnegie was promoted in 1852 to assistant operator, working for a monthly wage of twenty-five dollars (Carnegie, 55). In 1853, he started work for Thomas A. Scott at the Pennsylvania Railroad as a clerk for a monthly pay of thirty-five dollars (Carnegie, 61). After the end of the Civil War Carnegie started to get into the iron business and, later, the steel business; it was from these two industries that Carnegie made his fortunes 7 (Husband, 98). Part of Andrew Carnegie's success was due to his use of the Bessemer process for making high-quality steel, a process that he first saw used in England (Husband, 98). No account of Andrew Carnegie's life would be complete without mentioning a certain event that is associated with his name; thus, something should be said of the Homestead strike of 1892. Around 1881 Carnegie appointed one Henry Clay Frick as chairman of the Carnegie Company (Livesay, 131). It was Frick that was left to deal with matters concerning the Homestead strike while Carnegie was away in Scotland on his yearly trip (Livesay, 140). Livesay claims that 'Frick's attitudes toward the workers could only euphemistically be described as "haughty and disdainful."’ (Livesay, 136) Unlike Carnegie, Frick did not seek to be highly thought of by the workers (Livesay, 136). What followed was a disaster in which Frick used underhanded means and the workers and their allies turned extremely violent (Livesay, 139). Neither side came out looking admirable. In 1890 Andrew Carnegie formed the Carnegie Company, which became the Carnegie Steel Company in 1899. In 1901 this company was merged into the United States Steel Corporation, and around this time Carnegie retired from business. From then on he mainly pursued philanthropic activities (Husband, 100), making contributions towards libraries, educational institutions, leagues in the service of world peace, a Peace Palace in the Netherlands (Livesay, 188), and other public works (Husband, 101). After World War I started in 1914, Carnegie stopped working on his autobiography; in fact, 'Henceforth he was never able to interest himself in private affairs,' wrote his wife, Louise Whitfield, in 1920 (Carnegie, V). Livesay reports that 8 Carnegie died in his sleep on August 11, 1919 (Livesay, 188); he eulogizes Carnegie as such: ‘He was a collection of paradoxes, this man of American steel -- violent and peaceloving, ruthless and loyal, greedy and generous, boastful and diffident, vain and doubting, brash and shy.’ (Livesay, 189). 9 Carnegie’s Library Philanthropy Andrew Carnegie, commonly known as the “Steel King”, was one of the richest men in the world. However, people are less likely to call him the “Patron Saint of Libraries”, a term by which he is also known (Bobinski 3). In truth, Carnegie was a prominent philanthropist, and while this fact might elude many initial thoughts of the industry kingpin, his positive influence on libraries across the United States is worthy of great mention. There is no doubt that the man contributed greatly to the growth of libraries across America, and the field of Library Information Science was similarly improved by his efforts. This section will detail the philosophy, process, and ramifications of his contributions towards America’s libraries. By the turn of the 19th century, American public libraries were in dire need of assistance. Across the nation, librarians cared for books within buildings that were not entirely their own. Many of the libraries were, in fact, auxiliary areas in city halls or even residential neighborhoods that were converted by good-natured people. Some of the more bizarre locations were in a balcony office in Dillon, Montana, a building which housed horses for the firemen in Marsville, Ohio, and even a rest room. Yet, despite the fact that many of these public libraries were in shacks or poorly equipped structures, it showed people were willing to invest a great deal of time and effort in them. Unfortunately, dilapidated houses and dark basements were all the common folk could muster (Bobinski 34). Andrew Carnegie was a long time lover of books. He was also a man who invested vast amounts of energy and resources into improving libraries in the United 10 States. He gave away most of his riches to “the improvement of mankind,” donating a total of $333 million (roughly 90% of his wealth) to philanthropic endeavors (Bobinski 3). He used it to support construction of new libraries primarily in America, giving more than $40 million in donations to 1680 U.S. libraries in over 1400 communities (Dierickx 21). In 1901, after retiring and selling the Carnegie Steel Company, Andrew Carnegie turned his efforts to philanthropy. He was, at this time, sixty-six years of age. It is interesting to note that this philanthropic endeavor was not a spontaneous decision; rather, the businessman planned this ahead of time, as found in the evidence of a memorandum written around 1868 (Bobinski 10). It was to be a giant project built on enormous planning, and the intention was to help the public. Carnegie applied the same resourceful energies he had given to his business to his newfound good works. His overall reasoning for building libraries and giving back to the community was stated in two essays written in 1889: “Wealth” and “The Best Fields for Philanthropy” (Bobinski, 10). In the first essay, Carnegie describes the wealthy man as one who is obligated to live “without extravagance” and take care of their families as best they could. Their last duty, moreover, was to use the rest of their fortune to better the “common man” in “welfare and happiness”, but only if they possessed the drive to use the money wisely. Carnegie had no interest in giving away money to those who would not “help themselves” (Bobinski 11). His philosophy stressed less fortunate people to pursue self-improvement, to pull their lives up from poverty, much the way he had. Otherwise, he argued, neither side would truly benefit from the transaction. 11 The second essay detailed the areas philanthropists could support. The list was ordered from top to bottom: universities, libraries, medical centers, public parks, meeting and concert halls, public baths, and churches (Bobinski 11). Note here, interestingly enough, that libraries are the second highest on the list of Carnegie’s priorities for charity. Much like his first essay, Carnegie maintained his stride of helping not only people, but also institutions that would give back to the community. Though he was generous, Carnegie was also a shrewd philanthropist, one not interested in sinking funds into ventures which yielded no profit. In this case, profit was meant not in the conventional sense, but in positive results for the people. Consequently, Carnegie did not simply give away his wealth to anyone who requested it. A detailed investigation was involved in every claim from a community in which a library was needed, including questions pertaining to any existing libraries in town and how many people lived there. The money used for such requests was only donated if the community in question agreed to pay maintenance fees and provide enough resources for the library to be sustained without additional philanthropic help thereafter. This also meant that Carnegie would only authorize funds if the town had demonstrated that they had no other means of obtaining it. His secretary, James Bertram, oversaw the hordes of requests for libraries and rejected many for asking for more than what was offered. The spirit of Carnegie’s offer was to invoke empowerment of the people. It would be, after all, their library, and they should be the ones to have pride enough to take care of it. There are accounts of communities writing to Carnegie requesting libraries as gifts but also desiring “additions” added as though they were necessities. For example, in 12 one instance, the town of Sparta, Michigan requested funds for a two-story building with a basement. The first floor was to contain the library, the second floor entertainment and lecture rooms, and the basement was to include a bowling alley along with a bar. Other towns asked for funds as though the presence of a library was an afterthought; for instance, requesting libraries because all the town had was saloons (Bobinski 36). Bertram rejected all such requests, reasoning that if such projects were approved then it would give license for every other community to ask for more than a library. The fear was that many communities did not want one to begin with, and they submitted requests only in order to acquire the “additions” (Bobinski 37). Carnegie’s intent was to give libraries to communities who truly wanted them – no more, no less. This fact proved more significant after the papers were signed and the money was underway, because the funds provided were strictly for the construction of the library. It did not include staff, training, or book purchases. Soon, many communities realized that Carnegie’s gift came with significant annual maintenance costs that required more than mere grounds keeping, and that Carnegie would have nothing to do with these extraneous costs. Aside from the problems of honesty in statistics from local communities, Carnegie’s philanthropy occasionally incited full-blown battles. Workers of the Homestead steel strike of 1892 accused Carnegie of minimizing wages in order to pay for the libraries (Bobinski 103). Others accepted the gift with the assumption that they would receive nothing more from the kingpin. Mark Twain went so far as to mention Carnegie’s philanthropy as a sad, even pitiful experience. After visiting the steel tycoon, 13 Twain is quoted as having said, “He has bought fame and paid cash for it, he has deliberately projected and planned out this fame for himself…” (Bobinski 105) The muddled reputation Andrew Carnegie suffered because of the Homestead strike, combined with the strict procedures by which he offered his charity, served to produce mixed reactions from the American public. Despite this, Carnegie maintained that although he was providing the money, it was the communities’ responsibility to decide whether or not they wanted and could use a library. He simply provided the means to obtain a building, and if the people were truly spirited, they would find the resources to stock it with books, staff, and patrons to keep it successful. While his stance may have appeared indifferent, the movement for newly funded libraries was very successful, as can be seen by the resulting statistics and personal commentaries of those who benefited from his patronage. Many scholars of who focus on the public libraries of America have had much to say about Carnegie’s philanthropy. The overall feeling is that he chose to improve a resource in the United States that not everyone was able to appreciate. While the argument of increased wages and other more practical charities remained, it was a push in a higher direction. This is according to public library scholar Sidney Ditzion, who said Carnegie’s influence on the library movement in America was a “stimulant to an organism which might have rested long on a plateau had it not been spurred on to greater heights” (Bobinski 184). Mayor Rudolph Giuliani commended Andrew Carnegie in a letter to New York citizens, assuring the quality and excellence of his libraries (many of which are situated in the city) will continue for “generations to come” (Dierickx 5). Whether or not people 14 approve of the manner in which Carnegie offered financial support for libraries, the fact is he stimulated library development on a grand scale. By making certain the community would uphold their end of the bargain before living up to his, Carnegie was able to ensure long life-spans for the libraries he financed. The constant publicity Carnegie provided by giving libraries to hundreds of communities in itself made more people aware that such institutions existed. Many of Carnegie’s libraries still remain today, and though some have fallen into disuse, the memory and energy of his efforts have forever strengthened America’s library movement. 15 Andrew Carnegie and the Library of Hawaii Situated in the middle of the expansive Pacific Ocean, hundreds of miles removed from the continental United States, it is not difficult for the islands of Hawaii to be overlooked by mainland Americans. Indeed, to this day it is not difficult to find American citizens who are unaware that Hawaii is, in fact, part of the United States. But a part of the country it is, and like all of its fellow states, the state of Hawaii has benefited from the philanthropy of Andrew Carnegie. Despite its distance and remote location, Hawaii was not beyond or beneath the notice of Carnegie, and money provided by the steel tycoon went towards the construction of none other than what we citizens of the islands know today as the Hawaii State Library, located in Downtown Honolulu. However, the obtaining of a Carnegie grant for the construction of the Library of Hawaii was hardly a smooth process. Rather, it was filled with trials and errors, red tape, stonewalling, wheeling, dealing, and all the other delightful aspects of any issue heavily political in nature or implication. And through it all, that shadowy force that makes the world go round, money, was ever present. Having examined Carnegie’s life, and now possessing a measure of understanding of his philanthropy and the guidelines he required communities to follow in order to procure his grants for library development, this section will report on the history and process by which Andrew Carnegie gave his support for the development of the first public library building here in Hawaii. Andrew Carnegie agreed to release funds for the construction of a public library building in Hawaii in 1909. This marked the first time the philanthropist had provided 16 money for a library situated beyond the borders of the continental United States, though it was not the first library he had funded in the Pacific region; two years prior, he had given roughly $3,000 for the construction of a public library in Suva, Fiji (Ramachandran, 45). As mentioned earlier, the process of obtaining Carnegie’s contribution was not a quick and easy one. Citizens of Hawaii requested money from the steel tycoon-turnedphilanthropist on no fewer than four separate occasions, and the span of time from the first request to Carnegie’s signature of confirmation for a grant lasted roughly nine years. It may come as a surprise to some that the first request, submitted in 1901, did not actually come from the capitol of Honolulu. In order to explain why this was, as well as to set the stage for events in this particular timeline, it is necessary to look back at the status of the library movement in Hawaii during the late 1800s. First of all, it must be remembered that, up until 1893, Hawaii was still a monarchy and not yet part of the United States. The library movement of the time was focused around the Honolulu Library and Reading Room Association (HLRRA), which had been founded in 1879. The HLRRA, which had replaced the kingdom’s original library organization, the Honolulu Circulating Library Association, had developed the first subscription library in Hawaii and was responsible for increasing citizens’ awareness of the importance of books, literacy, and libraries. Logic dictated that the HLRRA would have been the perfect organization to request a grant from Carnegie. However, there was one catch: the HLRRA did not particularly need the money (Ramachandran, 45). Early in its history, the organization had established a solid economic foundation, and over time it was able to obtain the moral and financial support of both the Hawaiian government and wealthy citizens. King Kalakaua, Queen Kapiolani, Queen Emma, 17 Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, Regent Liliuokalani, Minister of the Interior F. W. Hutchinson, and C. R. Bishop were just a few of the notable and highly influential supporters of the HLRRA. Although the organization was unable to procure regular funding from the legislature, continued gifts of books, money, and space from the royalty and men of means were enough to keep it afloat. Additional monetary aid, say from a source like Carnegie, was considered unnecessary at the time. Thus it was that Hawaii’s first request for a Carnegie grant came not from the city of Honolulu, but from the town of Lihue, located on the island of Kauai. At the turn of the century, Kauai possessed no libraries to speak of. In the year 1900, one Reverend J. M. Lydgate, who was pastor of the Lihue Union Church and Kola Church, sought to rectify this by establishing a library in the town. Unfortunately for Lydgate, support proved to be extremely difficult to come by. With little interest (and therefore little monetary support) coming from the immediate community, Lydgate sought financial aid from elsewhere. As early as 1897, Andrew Carnegie’s reputation for assisting in the development of public libraries was well known across America, and this included the new Territory of Hawaii (the monarchy having been overthrown four years prior). As such, it was to Carnegie that Lydgate turned for support in his pursuit of building a library in Lihue. In January of 1901 Lydgate submitted a letter, endorsed by S. B. Dole, the first governor of Hawaii, requesting a grant from the great philanthropist. As Governor Dole had also been president of the HLRRA from 1882 to 1886, it was hoped that his signature would lend a measure of official as well as local library system support to Lydgate’s request (Ramachandran, 46). 18 Alas, Lydgate’s petition effectively failed before he even had a chance to submit it. As was reported in the previous section, Carnegie refused to provide grants to communities that demonstrated a lack of support to the idea of library development (as the citizens of Lihue had). Furthermore, Carnegie generally required proven long-term government support for any library or library system that might be developed; rarely did he approve petitions that came from individuals. Lydgate was not aware of the specific guidelines Carnegie had put in place, and as a result, this first request was rejected. One year later, the second request for a public library in Hawaii was put forth, and this time it came from none other than the HLRRA. Two main factors contributed to the organization’s decision to cease relying solely on the support of the community and instead seek a grant from Andrew Carnegie. The first was a need for both a new library facility and an expansion in services that would allow for book borrowing privileges for the general public. The second was the annexation of Hawaii in 1898. The overthrow of the monarchy had done away with the HLRRA’s royal patronage, and annexation resulted in economic and social conditions that were conducive to library development. Incoming Americans from the continental U.S. also brought with them a desire for library facilities. With shrinking budgets and growing demand, the HLRRA was ready to seek Carnegie’s help (Ramachandran, 47). In early 1902, communication began between the Vice-President of the HLRRA and Andrew Carnegie’s secretary, James Bertram. In his responses Carnegie appeared open to the idea of providing a grant for a public library in Hawaii, so long as his conditions for such grants were met. However, one of those conditions required that the HLRRA merge into and become part of the new library. That requirement, from the 19 viewpoint of the HLRRA, had the potential to seriously weaken the organization, potentially even driving it to extinction (Ramachandran, 48). As a result, by April of 1902 the HLRRA had concluded that it would not be able to meet Carnegie’s terms. The unwillingness of either side to yield or compromise doomed this second request to failure. In 1903 George R. Carter became governor of Hawaii. For nearly five years after the HLRRA’s attempt to procure a Carnegie grant for a public library, the matter stayed dormant. Then in 1907, Carter’s last year as governor, the third request to Andrew Carnegie was made, and this time it came from the office of the highest elected official in local government. From the HLRRA’s aborted attempt at a library grant in 1902, it was clear that Carnegie would settle for nothing less than full compliance with his standards before he would approve funding. Governor Carter sought to meet these standards. In order to address Carnegie’s desire to see long-term government support for any library that would be developed using his money, Carter first approached the legislature. He requested that the legislators provide $5,000 to go towards library development, arguing that this would demonstrate the interest of Hawaii’s citizens to Carnegie. Carter found the support he needed, and on April 9, 1907, the “Act to Establish the Hawaiian Library and to Provide for its Care and Management” was approved (Ramachandran, 47). Having overcome his first hurdle, Governor Carter next turned to the HLRRA. His hope was that gaining the support of the organization would demonstrate the interest of Hawaii’s library community towards the development of a public library. Alas, here Carter was stymied. The HLRRA, still fearing that accepting Carnegie’s terms would diminish their own power, refused to provide support. By May of 1907, the governor 20 was forced to concede defeat. Not long after, Carter was succeeded by Governor Walter F. Frear, and he left office with his plans for a Hawaii public library unfulfilled. While Governor Carter had been unsuccessful in his attempt to obtain a Carnegie grant, his efforts were not entirely in vain. Because of his actions, both members of the legislature and average citizens alike began to take an interest in the issue of library development in Hawaii. Thus it was that when Governor Frear took office, he was able to utilize public sentiment to aid him in pursuing what would be the fourth and final request for a Carnegie grant. Frear was further assisted in this endeavor when, in November 1908, the HLRRA found itself on shaky financial ground. With monetary resources and support dwindling, the organization was at last willing to reconsider the uncompromising stance that had doomed the previous two grant requests to failure (Ramachandran, 48). Governor Frear had met with Carnegie a couple of times during 1908 and had even written up a grant proposal in March of that year. Yet throughout this time the issue of the HLRRA merging with the new library remained a thorny one. However, when the governor returned to Hawaii early in 1909, it was to find the organization weakened financially and finally ready to deal. With this last and greatest obstacle removed, Frear was able to proceed with the grant request. Not long after, the “Act to Provide for the Establishment of the Public Library of Hawaii” was enacted (Ramachandran, 49). On May 15, the HLRRA and the Library of Hawaii signed an agreement by which the former agreed to turn over all books, furnishings, and remaining funds to the latter. A few months later, on November 16, the HLRRA, Library of Hawaii, and the Historical Society jointly signed and submitted a letter to Carnegie requesting a grant for the 21 construction of the Library of Hawaii (Matsushige, 4). Carnegie responded that the sum of $100,000 would be made ready as soon as a site was selected and plans drawn up. The site for the new library building was decided upon early in 1911, with the cornerstone being laid on October 21st of that year. David Starr Jordan, president of Stanford University and friend of Andrew Carnegie, represented the philanthropist at the ceremony. Ultimately, the Library of Hawaii was completed at a cost of $127,000, with the local legislature providing the difference. The building opened its doors on February 1, 1913, and Hawaii at last joined those states of America that offered free library services to their communities (Matsushige, 4). The library, now known as the Hawaii State Library, still stands today. Greco-Romanesque columns in front mark it as a Carnegie library, and within its lobby, a bust of Andrew Carnegie, the man who made it possible…perhaps not easily, but possible nonetheless…can be found. 22 Bibliography A Biography of Andrew Carnegie Carnegie, Andrew. The Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. orig. published Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1920. Northeastern University Press, 1986. Husband, Joseph. Americans by Adoption. Freeport, NY: Books for Libraries Press, 1920. Reprinted 1969. Livesay, Harold C. Andrew Carnegie and the Rise of Big Business. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1975. For basic (and brief) information, the chapter in Husband’s book is a good starting point, although it completely skips over the Homestead strike. Carnegie’s own autobiography is much longer and is somewhat more whimsical than the account given in Livesay’s book. Livesay, in his own ‘Notes on Sources’ section, accuses Carnegie of having a ‘self-serving memory’, and there is some plausibility to this charge, but Livesay seems to go too far in the opposite direction, being harshly critical of Carnegie. Carnegie’s Library Philanthropy Bobinski, George Sylvan. Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development. Chicago: American Library Association, 1969. This book by George S. Bobinski examines Andrew Carnegie and his involvement with American libraries. He explores correspondences between the philanthropist and his secretaries and the communities in which they were involved. Full of personal histories and anecdotes of Carnegie’s involvement, Bobinski’s book is rich with information on the various feelings and issues which drove the library movement forward and those that threatened it. This was found at the State Library. Dierickx, Mary B. The Architecture of Literacy: The Carnegie Libraries of New York City. New York: J.M. Kaplan Fund Publication program, 1996. Mary Dierickx lists the Carnegie libraries based in New York City, featuring pictures and detailed descriptions, histories, and any current available information. She also includes the architect responsible for the building and interesting facts about it. The pictures and diagrams are very interesting, and information researched about each library 23 is very specific. However, the book lacks specific details about Carnegie and focuses on the individual states of the libraries. This was also found at the State Library. Andrew Carnegie and the Library of Hawaii Matsushige, Hatsue. Library of Hawaii, 1913-1949. Thesis. Pratt Institute, 1951. This document was a graduate thesis and not a formal book. I came across it while using the Library of Congress Subject Headings that the UH Voyager system provided when I found the record for the item listed below. While the title of this book looked promising, there was precious little information on Andrew Carnegie’s role in the development of the Library of Hawaii. What was available was mostly limited to a single paragraph on one page. Still, the document did provide me with some key dates, and so still served a use. Ramachandra, Rasu. Origins of the Carnegie Grant to the Library of Hawaii (1901 1909). n.p., 1973. I anticipated that the topic of Carnegie’s role in the development of the Library of Hawaii would not have much in the way of resources. I was, regrettably, correct, and it was only because I came across this book during a Voyager search for other materials on Carnegie that I decided to pursue it at all. Because of the overall lack of books, articles, and even websites on this subject, I ended up depending heavily on this item. It contains a surprising amount of detail for so narrow and obscure a topic, although the timeline is occasionally difficult to follow and the document has a fair share of grammatical errors. At the end of the book one can find an excellent list of sources, many of them primary. Unfortunately, many of the items listed are in special collection such as the Hawaii State Archives, and given the comparatively short length of time we had to complete this assignment, I was unable to schedule any opportunity to view them for myself. 24