12595857_Main

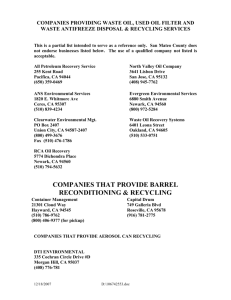

advertisement

Title: University community responses to on-campus resource recycling Published in: Resources, conservation & recycling Authors: T.C. Kelly, I.G. Mason, M.W. Leiss b, S. Ganesh Abstract In order to gain a better understanding of the attitudes and behaviour of a campus community toward a university concourse-based recycling scheme, a survey of 1400 students and staff, at Massey University, New Zealand was conducted. A written questionnaire focused on how recycling participation and source separation performance might be improved, and on general attitudes within the university community toward recycling. The recycling scheme was generally well supported, with predominantly positive recycling attitudes and self-reported recycling behaviour indicated for both students and staff. The major suggested improvement to the concourse system was to have better signage in more appropriate places, and therewas strong support for extension of the recycling scheme across the wider campus. Significant relationships were found between self-reported recycling behaviour and attitudes toward recycling, self-reported recycling behaviour and campus occupation (student, postgraduate student, academic staff, or general staff) and self-reported recycling behaviour and place of work. 1. Introduction Environmentally friendly management of resource residuals is a vital factor in moving toward the goal of a sustainable society. In this regard, the actions of reduce, re-use and recycle within the waste management hierarchy assume particular importance (Oskamp, 1995; Hamburg et al., 1997), especially in relation to public participation in waste management systems. Since successful recycling programmes depend not only on technology, but also on the involvement of people, the development and maintenance of environmentally responsible behaviour is of considerable importance. University communities possess a number of defining characteristics in comparison to the general population. A large student group, primarily in the adolescent and young adult age range, exists alongside a typically much smaller staff group with ages spanning the adult range. The community is highly educated, with personal income distribution generally at the low end of the range for students, and at the middle to higher end of the range for the staff group. In New Zealand, the recent gender balance across the overall university student population is slightly uneven, with 44% male and 56% female across all universities in 2001 and 2002 (MoE, 2001; MoE, 2002a), although this may be expected to differ elsewhere. University staffing ratios are similar, with 47% male and 53% female across all NewZealand universities in 2002 (MoE, 2002b). Studies of recycling behaviour, with university students as the subject population, have largely focused on the effects of short-term interventions, using prompts, rewards, feedback and/or education, on paper or beverage container recycling behaviour (Geller et al., 1975;Wittmer and Geller, 1976; Luyben et al., 1979; Luyben and Cummings, 1981;Wang and Katzev, 1990; Diamond and Loewy, 1991; Goldenhar and Connell, 1992; Katzev and Mishima, 1992; Austin et al., 1993). These investigations were conducted in North American college (university) settings, with studies by Katzev and Mishima (1992) and Austin et al. (1993) focussing on a student mailroom and two academic departments, respectively, and the remainder occurring within student halls of residence. In these studies, rewards were typically shown to result in greater recycling participation than either prompts or control scenarios. However, behaviour usually reverted to pre-intervention levels once the reward or prompt was removed. McCaul and Kopp (1982) found that goal setting increased beverage container recycling by college students, however, a public commitment approach did not result in any significant effect in this study. In contrast, Wang and Katzev (1990) found individual (room rather than person) commitment to be successful in increasing paper recycling by college students, but that a group commitment approach was unsuccessful. Inconvenience was reported as a major influence on college student recycling behaviour by McCarty and Shrum (1994), who further commented that such concerns appeared to outweigh attitudes about the long-term importance of recycling behaviours. Williams (1991), based on a telephone survey of undergraduate and graduate students at a North American university, reported that a lack of storage space was cited as the main reason for not recycling. However, two-thirds of students reported that they did recycle returnable bottles and cans, about one-half that they recycled newspapers, and one-fifth that they recycled non-returnable bottles and cans. A proposal for introduction of a university-wide recycling system was highly supported. Feedback (Goldenhar and Connell, 1992; Katzev and Mishima, 1992), and proximity of recycling containers (Luyben et al., 1979), have been found to be positively correlated with student recycling behaviour. Personal inconvenience has also been reported as a significant barrier to recycling in household studies (e.g., Oskamp, 1995). The applicability of the theory of reasoned action (TRA) and the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) in explaining student recycling behaviour has been examined by Goldenhar and Connell (1993), Cheung et al. (1999) and Rise et al. (2003). From their North American, halls-of-residence-based study, Goldenhar and Connell reported that intentions to recycle played a mediating role on the impact of attitudes and norms on student recycling behaviour. Past experience with recycling significantly influenced intent and behaviour for males only, whilst the relationship between norms and intent was statistically significantly greater for females, leading to the conclusion that gender specific interventions may be necessary for influencing recycling behaviour amongst young adults. Cheung et al. (1999), in their study of Hong Kong undergraduates (approximately 36% male and 64% female), found that whilst the TPB significantly predicted intent and self-reported behaviour, it could explain only 28–29% of the variance. Perceived difficulty was found to moderate the link between intention and behaviour, but perceived control had no significant impact. However, two additional factors, general environmental knowledge and past behaviour, were found to be significant in predicting recycling behaviour, with the latter explaining 34–35% of the variance. In a study of Norwegian university students, Rise et al. (2003) investigated the influence of implementation intentions (i.e., when, where and how to act) in predicting the performance of regular exercising and drinking carton recycling using the TPB model. For recycling, implementation intentions had a marginal mediating effect between either perceived behavioural control or behavioural intention and actual, self-reported, behaviour. The full TPB model explained 65.5% of the variance in recycling behaviour, with behavioural intentions as the strongest determinant and past behaviour also making a significant impact. In a structural modelling approach, McCarty and Shrum (1994) investigated the linkages between values, attitudes and recycling behaviour in a study of North American undergraduate students. Values were not directly related to self-reported recycling behaviour, but did directly influence attitudes about both the inconvenience and importance of recycling. For more general information on university student environmental attitudes in North America, Latin America and Australia, the reader is referred to Yount and Horton (1992), Forgas and Jolliffe (1994) and Schultz (2001). The vulnerability of a group of Canadian undergraduates (24% male, 76% female) to anti-recycling arguments was reported by Koestner et al. (2001). Highly introjected individuals (i.e., those who recycled because of guilt) were found to be influenced by the personal attractiveness of the source of anti-recycling arguments presented to them, rather than the strength of the argument. It was suggested that in order to promote long-term environmentally friendly behaviour, it is important for individuals to operate from truly integrated motivational factors, related to values and feelings that this behaviour is personally important, rather than from introjection. Barker et al. (1994) compared the self-reported and actual paper recycling behaviour of undergraduate students (38% male, 62% female) at a North American university. Whilst self-reported attitudes toward recycling and self-reported recycling behaviour were highly positive, only 13.5% of all participants in the study actually recycled. Of these recyclers, 14% (2) were male and 86% (12) were female. In considering the overall relevance of past social science research on recycling, Oskamp (1995) has issued a cautionary note regarding generalisation across approaches, localities and times, commenting that past findings may be less relevant to current conditions. For example, in situations where recycling participation has become a widespread and normal behaviour, personal characteristics related to earlier recycling behaviour may have little or no relevance. Conversely, in places where recycling is virtually unknown, such findings may well be of value. A Zero Waste program was initiated at Massey University, New Zealand, in 1999, with the aim of promoting an ongoing commitment to demonstrably sound environmental management in the areas of both physical and energy resources (Mason et al., 2003). One of the initial foci of the overall program was on the source separation and quantification of solid resource residuals arising from the student cafeteria, kitchen and concourse areas on the campus. A system of recycling bins was established in these areas, a publicity and education campaign launched, and a study of the types and quantities of materials collected conducted between January–April, 2000. Bins located within the main student cafeteria dining and kitchen areas were accompanied by signage, indicating which materials were to be deposited in each bin. In the concourse area, the bins were colourcoded according to the material category to be deposited, with green for food residuals plus food contaminated paper, blue for all other paper and cardboard, yellow for selected plastics and black for “rubbish”, and labelled with the words food, paper, plastics, and rubbish, respectively. Details and results of the source separation study have been reported by Mason et al. (2004). Sign-boards were not present in the concourse area at this time, but were erected at three locations shortly following the completion of the initial study period in April, 2000. Prior to the implementation of the Zero Waste program, a paper recycling system operated with limited success within some departmental buildings, and a central glass collection point was sited within a short distance of the student centre. Otherwise, recycling facilities were largely absent from the campus. Within the adjacent city of Palmerston North, however, where many students and a majority of staff reside, full kerbside recycling has operated since late 1997, in addition to several pre-existing recycling centres. Public awareness of recycling is relatively high throughout New Zealand and between 1999– 2003, 54% (39/74) of the local authorities in New Zealand, including Palmerston North, formally adopted Zero Waste policies (ZWNZ, 2004). Apart from the study reported by Austin et al. (1993) there appears to be no information in the literature about university community responses to recycling programs. This paper reports on a study undertaken to assess the level of participation in a recycling scheme by a university community, and to understand ways in which participation in general, and source separation in particular, might be improved. 2. Methods 2.1. Location The study took place in 2001 at the Massey University Turitea campus, which is situated in Palmerston North, NewZealand (latitude 40 ◦ S). Following the source separation project, the recycling system was left in place, with residuals collection subsequently operated by University Facilities Management staff. The location of the source separation study area and the layout of the concourse bin clusters are shown in Fig. 1. Details of the recycling instructions for the cafeteria and kitchen areas are given in Mason et al. (2004), whilst those for the concourse area are shown in Fig. 2. 2.2. Survey design and administration A written 8-page questionnaire was developed comprising four sections: (1) knowledge of and self-reported participation in the Massey University recycling system; (2) opinions about the system and ways to improve it; (3) general attitudes toward recycling and the environment; and (4) demographic information. Responses were indicated via tick boxes and Likert scales, with spaces for written comments provided. The complete mail-out kit contained the questionnaire, a formal personalised letter of introduction, an information sheet about the recycling scheme and a return, post-free envelope. Returns were able to be mailed via public mailboxes, the internal university mail system and also deposited into two drop boxes, positioned at prominent locations on the campus. A sample of 1400 people, comprising 1000 students and 400 staff, was selected from an estimated total campus population of 6500 students and 1800 staff. Student names were selected randomly from university records, and the 400 staff members were randomly selected from the Massey University staff telephone list. The sample was split into students and staff in order to enable data from each group to be analysed separately, as it was expected that staff members would constitute a significantly different demographic group from students, and thus, there was reason to expect some difference in attitudes and behaviours. As an incentive to encourage people to return the questionnaire within two weeks of the mail-out date, timely respondents were eligible to participate in a draw for four modest prizes (dinner vouchers).A unique ID-number was printed in one corner of the questionnaire in order to keep records of respondents, to identify non-respondents who were sent a single follow-up written reminder, and to identify those people eligible to participate in the draw for the four prizes. The survey procedure was anonymous and was approved by the Massey University Human Ethics Committee. 2.3. Data analyses The Chi-square test for independence was utilised to examine the significance of interdependence between selected responses. Significant interdependence was further examined using correspondence analysis (Greenacre, 1984; Hair et al., 1998). Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS System software version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). 3. Results and discussion 3.1. Response rate The total number of respondents was 678 (448 students and 230 staff), giving an overall response rate for the survey of 48.4%. Staff responded at a slightly higher rate (58%) than the students (45%). Surveys sent to 12% of the staff and 4.3% of the students were returned as not contactable. Assuming that the samples were heterogeneous, and given that the sample sizes were a significant proportion of the total populations, sampling errors at the 95% confidence level were 3.6% overall (6.1% for staff and 4.5% for students) (Moser and Kalton, 1971; de Vaus, 2002). 3.2. Sample characteristics The sample consisted of about two-thirds students and onethird staff (Table 1). The gender balance for both groups was similar to that previously reported for New Zealand universities (MoE, 2001; MoE, 2002a, 2002b). Just over half of those sampled were under 25 years of age, with the modal group being the 20–25 age bracket. Over 60% of the respondents earned less than NZ$20,000 annually and 30% earned between NZ$20,000 and NZ$60,000 per year. Interestingly, over half of all respondents were from the College of Sciences. It should be noted that the College of Education was situated approximately 3 km from the Turitea campus, meaning that staff and students from this college were less likely to frequent the study area. 3.3. Campus recycling awareness and self-reported participation The awareness of the four-bin recycling scheme was high for both students (96%) and staff (86%). The reason for the higher awareness of students might be attributed to the fact that they frequented the concourse area more often than did staff (77% of students were there at least once per week, while only 45% of staff frequented the area at least weekly). Of those who were aware of the scheme, 95% of staff and 76% of students had used it at least once. About half of the respondents described themselves as frequent recyclers on campus while less than 7% said they never recycled. Nearly, half (49%) of all respondents said they always recycled waste when on the concourse and a further quarter frequently recycled when on the concourse. Only 57% of respondents were aware of the signage accompanying the bins, which is much lower than those who were aware of the bins themselves. This suggested that the signs were not noticeable enough, in the wrong places, or were just too few in number. Of those who knew about them, 80% found them helpful (77% of students; 87% of staff). 3.4. Potential for improvements to the recycling scheme Sixty percent of the university community were ‘generally happy’ with the design of the recycling bins, and 58% agreed that changes in the set-up, design and size of the recycling bins would not change their recycling behaviour. Most respondents did not express strong preferences for changes in the design attributes of the recycling scheme, though there was some support for brighter coloured bins (Table 2). The majority of respondents indicated that they would not change their recycling behaviour if the number of categories of recyclables was either decreased or increased. Asked if they would recycle more often if they did not have to separate recyclables into so many categories, 76% of respondents (72% of students; 83% of staff) said they would not be affected, while 20% (23% of students; 15% of staff) said they would recycle more often. Likewise, if there were more categories in which to recycle, 62% (56% of students; 72% of staff) indicated that they would not change their behaviour and the remainder were split about evenly between recycling more often and less often. A slight majority of the university community (56%) reported that they did not want more information, either on the university recycling scheme or on recycling in general. Most respondents did not agree that they would recycle more if they had more information per se (Fig. 3k). As discussed earlier, recycling is widespread in New Zealand and many local authorities have signed up to a zero waste policy. However, 50% of respondents (53% of students, 46% of staff) indicated that they would recycle more often given specific information on what happens to recyclables following collection. A majority of respondents (71%) signalled that social pressure would not cause them to recycle more (Fig. 3j). The response was notably stronger for staff (80%) than for students (66%) In response to questions concerning wider recycling participation, 83% of students and 69% of staff stated that they would recycle more if there were more bins around campus. When asked where they would put these new bins, the suggested locations were spread throughout the campus and9%of respondents said theywanted bins everywhere on campus. When exploring such “convenience” factors a significant relationshipwas found between occupation (i.e. undergraduate student, postgraduate student, academic staff, or general staff) and the question: If there were more bins around campus, would you recycle more? (χ2 = 20.04, d.f. = 3, p = 0.0002). Correspondence analysis revealed that staff were more associated with no while students were more associated with yes in response to the question. This makes sense since students typically frequent a greater variety of campus locations than do staff. Most other relationships concerning “convenience” factors were not significant. Several issues stood out in the comments that respondents made about the recycling scheme and recycling in general. Comments regarding the signage focused on both increasing awareness and providing information. Some respondents wanted to see more and bigger signs in more noticeable places nearer to the bins, and even on the bins themselves. A number of respondents also indicated that even with the signs, they were still confused and not sure where to put their waste. Proposed improvements for the signs included pictures on the signs which show the most common types of waste that go into the appropriate bins, less text on the signs to make them less confusing and, to the contrary, more details. Since some respondents also said that the reason for their not recycling was their ignorance of what types of waste go where and their fear of putting something into the wrong bin. A number of respondents commented more generally on the need for better information and education on recycling and the recycling scheme (although the majority of respondents did not want more information), and the need for promoting the scheme (e.g. through the student newspaper, radio station, and at orientation). Many comments were directed at the need to improve the wider convenience of recycling, primarily by providing more bins at a greater diversity of locations on campus, especially in student accommodation areas. Some advocated providing some form of incentive to recycle, such as prizes or awards, while others suggested removing ‘rubbish’ bins altogether to force people to recycle, though as some pointed out, this would mean that recyclables would be contaminated with non-recyclables. Another issue reported by a number of the respondents, and other observers, was that the university facilities management staff member who emptied the recycling bins had been seen transferring the contents of two or more bins into a single rubbish bag. This proved to be very discouraging and some respondents said they thus considered the whole recycling scheme to be a farce and not worth participating in. 3.5. Attitudes and environmental behaviour Responses to questions addressing attitudes and beliefs were, in many cases, highly skewed toward strongly agree, or strongly disagree (Fig. 3a–c and e–h). An overwhelming 98.7% of respondents thought that recycling was beneficial for the environment (Fig. 3e), however, only about half reported to be frequent recyclers, either on campus or at home. Most respondents reported strong beliefs on the positive role of recycling (Fig. 3e, f and h). Significant relationships were found between self-reported recycling behaviour on campus and responses to the statements: (1) It is my personal responsibility to recycle. (χ2 = 87.93, d.f. = 6, p < 0.0001); (2) I don’t think recycling has many positive effects on the environment (χ)2 = 43.92, d.f. = 6, p < 0.0001); (3) Disposing of waste in a landfill is no worse than recycling (χ2 = 31.51, d.f. = 6, p < 0.0001); and (4) Whether I recycle or not makes no difference (χ2 = 58.76, d.f. = 6, p < 0.0001). These findings are in contrast to previous investigations into links between personal values, attitudes and a range of pro-environmental behaviours, in which the link has typically been weak (McCarty and Shrum, 1994; Oskamp, 1995; Chan, 1998; Scott, 1999; Biswas et al., 2000). However, as reported by Barker et al. (1994), self-reported behaviour may differ from actual behaviour. Differences between staff and students in reported recycling attitudes and behaviour could be seen in several responses. Forty-two percent of students and 70% of staff reported to be frequent recyclers at home. Seventy percent of staff strongly agreed that the natural environment was of great importance to them, while only 54% of students did (Fig. 3a). Eighty-three percent of staff members agreed with the statement: I make a great personal effort to recycle as much as possible, with 44% strongly agreeing (Fig. 3b). Only 56% of students agreed with the statement, with only 17% agreeing strongly. Forty-eight percent of staff strongly agreed that it is their responsibility to recycle; only 27% of students felt the same (Fig. 3c). Just 28% of all students had an uneasy or bad feeling when throwing recyclable material into a normal rubbish bin in contrast to 49% of the staff. Finally, staff members engaged in more environmentally friendly activities than did the students. All of this is consistent with previous studies, where demographic factors like age and income have a positive effect on recycling attitudes and behaviour (Hamburg et al., 1997; Scott, 1999; Biswas et al., 2000). Schultz et al. (1995) listed personality, demographics and attitudes of environmental concern as personal variables, some of which may be related to recycling behaviour (e.g. high income has been reported as a good predictor of recycling behaviour). This study found a significant relationship (χ2 = 23.36, d.f. = 6, p = 0.0007) between the occupation of the respondent (undergraduate student, postgraduate student, academic staff, or general staff) and their on-campus recycling behaviour. The nature of this relationship, as revealed by correspondence analysis, appeared to be predominantly a contrast between undergraduate students recycling sometimes on campus against general staff and postgraduate students (and to a lesser extent, academic staff) recycling on campus frequently. There was also a significant relationship between the respondent’s age grouping and on-campus recycling behaviour (_2 = 34.61, d.f. = 6, p = 0.0001), with the younger groups tending to recycle sometimes, and the middle age groups tending to recycle more frequently. Given that age has previously been shown to be a significant factor in recycling behaviour, this suggests that programs to increase university community recycling might consider targeting students and staff separately. However, correspondence analysis also indicated that postgraduate students’ responses tended to be more closely aligned with those of staff, than of undergraduate students, signalling that separate targeting of postgraduate students may also be warranted. There appeared to be weaker but still significant (p < 0.05) relationships between on campus recycling behaviour and college of study/work (χ2 = 15.59, d.f. = 6, p = 0.0161), and income level (χ2 = 13.59, d.f. = 6, p = 0.0345).However, there was no significant relationship between on-campus recycling behaviour and gender, which is inconsistent with other studies (e.g. Goldenhar and Connell (1993)). 4. Conclusions Pro-environmental and recycling attitudes were shown to be generally positive on the campus. Awareness of the recycling scheme on the concourse was high and reported participation rates showed that the scheme was relatively well supported by students and staff. The majority of the community were generally happy with the design of the concourse scheme, with no real support for changing the number of categories for separation, or for a change in bin size. There was limited support for more brightly coloured bins. However, a need for improved and increased signage, showing which residuals should be placed in which bin, was strongly signalled. Two factors indicated as inhibiting people on campus from recycling more were a lack of scheme-specific information and, in regards to wider participation, inconvenience. Responses indicated that recycling could be improved by (1), providing information on the fate of recyclables following collection, and more widely practised by (2), making it more convenient, mainly with the introduction of more bins in strategic areas. There was little support for increased provision of general information about recycling per se, however, and social pressure was not indicated as a strong potential motivator to recycle. Overall, the responses showed strong support for extension of the recycling scheme from the concourse area to the remainder of the campus. A significant relationship between attitudes toward recycling and self-reported recycling behaviour was found, in contrast to previous reports in the literature. The study also demonstrated significant correlations between campus occupation and self-reported behaviour, and between place of work and self-reported behaviour. Acknowledgments The authors wish to thank DanielG´erard and HaiAnBui for technical assistance. Funding support from the Zero Waste NZ Trust and Massey University is gratefully acknowledged. References Austin J, Hatfield DB, Grindle AC, Bailey JS. Increasing recycling in office environments – the effects of specific, informative cues. J Appl Behav Anal 1993;26(2):247–53 Barker K, Fong L, Grossman S, Quin C, Reid R. Comparison of self-reported recycling attitudes and behaviors with actual behavior. Psychol Rep 1994;75(1):571–7 Biswas A, Licata JW, McKee D, Pullig C, Daughtridge C. The recycling cycle: an empirical examination of consumer waste recycling and recycling shopping behaviors. J Public Policy Market 2000;19(1):93–105 Chan K. Mass communication and pro-environmental behaviour:waste recycling in HongKong. J Environ Manage 1998;52(4):317–25 Cheung SF, Chan DKS, Wong ZSY. Re-examining the theory of planned behavior in understanding wastepaper recycling. Environ Behav 1999;31(5):587–612 de Vaus DA. Surveys in social research. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin; 2002 Diamond WD, Loewy BZ. Effects of probabilistic rewards on recycling attitudes and behavior. J Appl Social Psychol 1991;21(19):1590–607 Forgas JP, Jolliffe CD. How conservative are greenies – environmental attitudes, conservatism, and traditional morality among university-students. Aust J Psychol 1994;46(3):123–30 Geller ES, Chaffee JL, Ingram RE. Promoting paper recycling on a university campus. JEnviron Syst 1975;5:39–57 Goldenhar LM, Connell CM. Effects of educational and feedback interventions on recycling knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. J Environ Syst 1992;21(4):321–33 Goldenhar LM, Connell CM. Understanding and predicting recycling behavior – an application of the theory of reasoned action. J Environ Syst 1993;22(1):91–103 Greenacre MJ. Theory and applications of correspondence analysis. London, UK: Academic Press; 1984 Hair JF, Anderson RE, Tatham RL, Black WC. Multivariate data analysis – with readings. 5th ed. New Jersey, USA: Prentice-Hall Inc.; 1998 Hamburg KT, Emdad Haque C, Everitt JC. Municipal waste recycling in Brandon, Manitoba: determinants of participatory behaviour. Can Geogr 1997;41(2):149– 65 Katzev R, Mishima HR. The use of posted feedback to promote recycling. Psychol Rep 1992;71(1):259–64 Koestner R, Houlfort N, Paquet S, Knight C. On the risks of recycling because of guilt: an examination of the consequences of introjection. J Appl Social Psychol 2001;31(12):2545–60 Luyben PD, Warren SB, Tallman TA. Recycling beverage containers on a college campus. J Environ Syst 1979;9(2):189–202 Luyben PD, Cummings S. Motivating beverage container recycling on a college campus. J Environ Syst 1981;11(3):235–45 Mason IG, Brooking AK, Oberender A, Harford JM, Horsley PG. Implementation of a zero waste program at a university campus. Resources Conserv Recycl 2003;38(4):257–69 Mason IG, Oberender A, Brooking AK. Source separation and potential re-use of resource residuals at a university campus. Resources Conserv Recycl 2004;40(2):155–72 McCarty JA, Shrum LJ. The recycling of solid-wastes – personal values, value orientations, and attitudes about recycling as antecedents of recycling behavior. J Business Res 1994;30(1):53–62 McCaul KD, Kopp JT. Effects of goal setting and commitment on increasing metal recycling. J Appl Psychol 1982;67(3):377–9 MoE. 2001. Students at public tertiary providers. http://www.minedu.govt.nz NZ Ministry of Education,Wellington, New Zealand, Accessed 30 March, 2004 MoE. 2002a. Students at public tertiary providers. http://www.minedu.govt.nz NZ Ministry of Education,Wellington, New Zealand, Accessed 06 April, 2004 MoE. 2002b. Statistical tables on tertiary staffing 2002. http://www.minedu.govt.nz NZ Ministry of Education, Wellington, New Zealand, Accessed 06 April, 2004 Moser CA, Kalton G. Survey methods in social investigation. Aldershot, England: Dartmouth Publishing; 1971 Oskamp S. Resource conservation and recycling: behavior and policy. J Social Issues 1995;51(4):157–77 Rise J, Thompson M, Verplanken B. Measuring implementation intentions in the context of the theory of planned behavior. Scand J Psychol 2003;44(2):87–95 Schultz PW, Oskamp S, Mainieri T. Who recycles and when – a review of personal and situational factors. J Environ Psychol 1995;15(2):105–21 Schultz PW. The structure of environmental concern: concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J Environ Psychol 2001;21(4):327–39 Scott D. Equal opportunity, unequal results – determinants of household recycling intensity. Environ Behav 1999;31(2):267–90 Wang TH, Katzev RD. Group commitment and resource conservation – 2 field experiments on promoting recycling J Appl Social Psychol 1990;20(4):265–75 Williams E. College-students and recycling – their attitudes and behaviors. J College Student Dev 1991;32(1):86–8 Wittmer J, Geller ES. Facilitating paper recycling: effects of prompts, raffles and contests. J Appl Behav Anal 1976;9:315–22 Yount JR, Horton PB. Factors influencing environmental attitude – the relationship between environmental attitude defensibility and cognitive reasoning level. J Res Sci Teaching 1992;29(10):1059–78 ZWNZ, 2004. What’s NZ doing? http://www.zerowaste.co.nz Zero Waste New Zealand Trust, Auckland, New Zealand, Accessed 06 April, 2004

![School [recycling, compost, or waste reduction] case study](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/005898792_1-08f8f34cac7a57869e865e0c3646f10a-300x300.png)