the role of primary/secondary control in positive psychological

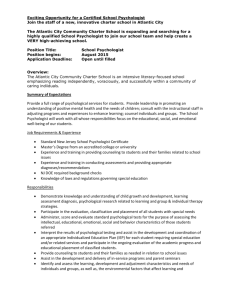

advertisement