Individual Career Anchors in the Context of Nigeria

advertisement

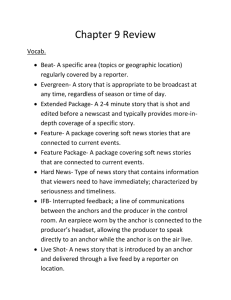

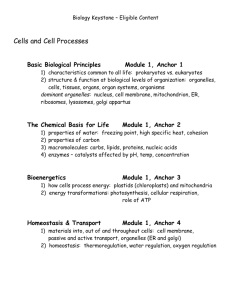

Moving Beyond Schein’s Typology: Individual Career Anchors in the Context of Nigeria Afam Ituma and Ruth Simpson Brunel Business School, Brunel University ABSTRACT Purpose –Drawing on institutional theory, this study sets out to explore the career anchors that exist among information technology (IT) workers in Nigeria and also to establish the strongest anchors in this context. Design/methodology/approach–This research adopted a two-pronged methodological approach, which involved the use of 30 semi structured interviews and 336 questionnaire survey. Findings – Results suggest the continued significance of traditional orientations to careers in Nigeria as well as orientations associated with new career theory. Research limitations/implications –The extent to which the findings of this research can be generalized is constrained by the selected context of the research. Practical implications-HR managers in Nigeria should be cautious of adopting career management models developed in the West. They should provide a reward system, which minimises financial uncertainty and risk. Originality/value –This paper provides valuable insights on the career anchors of IT workers in a relatively neglected region in the literature. It also extends Schein’s original career anchor theory. Article Type: Research paper KEY WORDS: Careers, Career Anchor, Nigeria, IT workers, Developing countries The authors are grateful to John Blenkinsopp, Newcastle University Business School, UK for his valuable comments and suggestions on an earlier draft. 1 INTRODUCTION Over the past few years, there has been a growing research interest in the influence of national culture and societal institutions on careers (recent examples include Baruch, 2004; Thomas and Inkson, 2006). There is a broad consensus among these scholars that careers are shaped and constrained by the socio-cultural and economic factors embedded in different national contexts. Despite recognition of the importance of such contextual factors for shaping individual careers, the career literature has largely neglected to account for career dynamics in diverse national contexts (Thomas and Inkson, 2006). Our knowledge of individual careers has accordingly been largely informed by research and models developed in Western developed countries (Budhwar and Baruch, 2003) and so may not accurately reflect the careers of individuals in other national contexts. In this respect, the career anchors of workers in less developed countries is a neglected and little understood area of inquiry (Counsell, 2002; Pringle and Mallon, 2003). Drawing on institutional theory and through a study of a particular group of skilled workers in Nigeria–specifically those involved in information technology–we aim to fill this research gap. Moreover, in contrast to the majority of empirical work which has focused on the “external” career i.e. the externally visible roles or offices held by an individual, we explore the nature of the “internal” career which concerns internal values, interests and motives held dearly by an individual (Gattiker and Larwood, 1988). The internal career is typically conceptualized in terms of career orientations or career anchors (Sparrow and Hiltrop, 1996). Drawing on Schein’s (1978) work, these refer to the constellation of self-perceived attitudes, values, needs and talents that develop over time, and which shape and guide career choices and directions. An understanding of the career anchors of individuals is important because congruence between individual anchors and work environment is thought to lead to positive career outcome such as job effectiveness, job satisfaction and high retention while incongruence is likely to lead to job dissatisfaction and high turnover (Schein, 1978). The overall objective of this paper is thus to contribute the Nigerian perspective and context to the wider discourse on the socially constructed nature of careers. In doing 2 so the paper will explore the different dimensions of career anchors that exist among a specific group of workers in Nigeria as well as the relative importance attached to each anchor. CAREER PERSPECTIVES A common view in the growing literature on careers is the notion that careers have an external as well as an internal dimension. The external career concerns the series of positions or offices which an individual holds (Sparrow and Hiltrop, 1996; Nicholson, 2000) while the internal career, as noted above, concerns the internal values, interests and motives held by an individual (Sparrow and Hiltrop, 1996). Most research and theory about careers have evolved around these two dominant views. However, despite consensus among scholars that careers have these two dimensions, Arthur and Rousseau (1996) found that more than 75% of the career-related articles published in major journals between 1990 and 1994 focused on the external aspects of career. By contrast, research on the internal dimension has been relatively neglected. However, the internal career is increasingly being recognised as significant as individuals are expected to take greater responsibility for both the direction and interpretation of their unfolding careers (Hall, 2002). This development is associated with new career theory (e.g., Hall and Mirvis, 1996) which suggests a rise in “boundaryless” or “protean” careers. These conceptualise a “new deal” whereby the traditional career (where salary, status and a secure career ladder within a single organization are exchanged for loyalty and commitment) may be giving way to the need for individuals to take responsibility for their own career management in a more uncertain environment, where career paths go beyond the boundaries of a single organization (Hall, 1996) and where there is an emphasis on portable skills and on meaningful work (Hall and Mirvis, 1996). A foundational model for understanding individuals’ internal careers is Schein’s career anchor theory. Schein (1987) defines a career anchor as “that one element in our self-concept that we will not give up, even when forced to make a difficult decision” (p.158). Schein’s (1978) seminal work on career anchors suggests that there are eight major types of career anchors that drive individuals’ career decisions. These 3 anchors are (1) security and stability (the desire for security of employment and benefit); (2) autonomy and independence (the desire for freedom to pursue career interests that is free of organizational constraints); (3) technical/functional competence (the desire for enhanced technical competence and credibility);(4) managerial competence (the desire for managerial responsibilities);(5) entrepreneurial creativity (the desire to create and develop new products and services); (6) service and dedication to a cause (the desire to engage in activities that improves the world in some ways); (7) pure challenge (the desire to overcome major obstacles and solve almost unsolvable problems) and (8) life style (the desire to integrate personal and career needs). Schein’s career anchor theory is founded on the premise that congruence between individuals career orientation and work environment will result in job satisfaction and increased commitment while incongruence will result in job dissatisfaction and turnover (Feldman and Bolino, 1996). The main assumption underpinning Schein’s career anchor theory is that an individual can only have one career anchor and this anchor is unlikely to change once it is developed. This suggests that individuals will seek job opportunities that strengthen this anchor rather than undermine it. Although Schein’s career anchor theory has received empirical support (e.g., Igbaria et al, 1991; Petroni, 2000), there have been several critiques. Feldman and Bolino (1996), for example, question the notion that individuals can only have one stable career anchor arguing that it is possible for individuals to have multiple important career anchors, as individuals are likely to have multiple important career and life goals. Despite this criticism, as Igbaria et al. (1991) note, Schein’s career anchor model is a helpful foundation from which to explore individual career choices and the reaction of employees to different career development opportunities. Thus, it has been applied to different occupational groups to understand the needs individuals aspire to fulfil. Within the area of IT, Ginzberg and Baroudi (1992) identified challenge and service as the most dominant anchor in US, Igbaria and McCloskey (1996) identified job security and service to be the dominant anchors in Taiwan, Igbaria, et al. (1995) identified service and job security as the most dominant anchor in South Africa while 4 Danziger and Valency (2006) identified lifestyle as the most dominant anchor in Israel. Although these studies provide valuable insight on the career anchors held by IT workers, they yield conflicting empirical result on the importance attached to each anchor in different national contexts. Further, one inherent limitation of these studies is that they apply Schein’s career anchor inventory to their respective samples without modification for differences in national context. It is unlikely that Schein’s US based framework, reflective of its unique social structures and institutions, will fully capture the career orientations of individuals in different national contexts because of the likely impact of societal institutions and national culture. Put together, while the work of Schein provides a sound starting point for developing an understanding of the nature of individuals’ internal careers, it may not capture the unique career experiences of individuals in different national contexts. As discussed earlier in this paper, the dominance of the Anglo-American perspective in the career literature may well have marginalised the significance of non Western based factors in our understanding of career development. As a result, we know relatively little about the dimensions of and importance attached to career anchors that exist among individuals in developing countries such as Nigeria. In order to fill this research gap, this paper addresses the following research questions: What are the different dimensions of career orientations that exist among skilled (specifically IT) workers in Nigeria? In this context, what is the relative importance attached to each career anchor? INSTITUTIONAL INFLUENCE ON CAREERS - THE NIGERIAN CONTEXT In addressing the above questions, this paper draws on institutional theory which, seeks to describe how human behavior is shaped and regulated by social structures. This theory suggests that individual behaviours reflect and mimic societal 5 conventions, values, beliefs and norms. Scott (2004) notes that there are three “pillars” of institutional processes: the regulative pillar (rules and laws that exist to ensure stability and order in societies), the normative pillar (domain of social values, norms, traditions), and the cognitive pillar (established cognitive structures in society that are taken for granted such as mental models, beliefs). An important implication of the institutional perspective is that individuals do not always take rational decisions, rather decisions and behaviour are framed by certain presupposed expectation. These expectations in turn legitimise individual actions and determine behaviour. Drawing from the institutional theory perspective, one can argue that the meanings attached to career and the trajectories of careers will be context dependent. In the Nigeria context, key factors that are likely to shape individual career decisions include its specific economic conditions and socio-cultural factors (Ituma and Simpson, 2006). In terms of the former, career decisions are taken in the context of an uncertain and insecure economic environment. While Nigeria is currently the world’s seventh largest oil exporter, producing about 2.2 million barrels a day, its economy has been ranked as the 19th poorest in the world (World Bank, 1997). The present state of the Nigeria’s economy is characterized by uncertainty, high unemployment levels in many sectors and a lack of an established welfare system. In terms of Scott’s “regulative pillar”, there is no specified minimum wage for skilled workers in Nigeria. As noted by Ovadje and Ankomah (2001) the Nigerian Labour Act which stipulates national minimum wage, does not cover persons in administrative, executive, technical and professional positions. These categories of employees are expected to negotiate individually with their employers. Moreover, unlike in most Western developed economies, credit facilities are hard to obtain and only available at very high interest rates. Thus, most workers spend a large proportion of their salaries meeting basic food and utilities needs and, as Ituma and Simpson (2006) found, often give priority to career moves that will better their economic circumstance. In terms of its socio-cultural context and Scott’s “normative pillar”, Nigeria is a country with a rich cultural heritage. One of the main features of Nigeria’s distinctive culture is the importance attached to the extended family system. Here, close and not so close family members (e.g. distant cousins and their spouses and children) form a 6 social network of relationships which serves as a form of social insurance. In essence, the extended family system reinforces values such as sharing and mutuality, adherence to social obligations and the need to maintain strong social and personal relations. These values and practices exert normative pressures toward behaviours oriented towards obligations and commitments which, to some extent, stand in place of the established social security and welfare systems of more developed countries. In terms of Scott’s cognitive pillar, these factors are likely to impact on the way individuals in Nigeria view their obligations and hence the meaning attached to their career. Individuals in Nigeria are likely to make career choices taking into consideration the socio-economic conditions and the obligations and commitments they have as a result of their membership of the extended family institution. These “mental modes” concerning career goals are likely to mediate the relationship between career orientation and subsequent career choice. RESEARCH APPROACH The research was conducted in two phases and adopted a mixed method approach, involving the use of semi-structured interviews (in the first phase) and questionnaires (in the second phase). The two methods are discussed in detail below. The research sample was drawn from IT workers in Nigeria. IT workers can be seen to be characteristic (in terms of educational background, training, skills, job components) of the more general category of skilled labour. This has potential to enhance the generalisability of the findings beyond the specificities of this particular occupational group. THE QUALITATIVE METHOD The qualitative approach involved interviews with 30 IT workers (9 women and 21 men) between February and April 2004. The interview participants were randomly selected from the membership list of Nigerian Computer Society. Participants’ age ranged from 26-45 years. Their tenure in the industry varied from 5-9 years, while their educational qualification varied from professional IT certificate to Master’s 7 degree. An interview protocol was adapted from Schein’s (1990) career anchor interviews. The interview questions are shown in Table 1. Analysis of the qualitative date involved the use of a grounded theory approach which involved developing concepts, categories and theories that are “grounded” in the collected field data (Strauss and Corbin, 1990). The first stage involved the verbatim transcription of interview data. Secondly, a coding scheme was developed to organise data and to segment and identify patterns of response. Different codes were subsequently developed to capture the motivations underpinning career/job changes. Finally, codes with similar characteristics were identified and where appropriate amalgamated to form categories. Any category that shared common elements with another was amalgamated to form a core category. At this stage, the data revealed six dominant categories representing the different career interests expressed by the participants. To enhance the validity of the findings, independent coding on a random sample of the transcript was undertaken by two researchers, both familiar with the objectives of this research and with significant past experiences in applying qualitative coding procedures. Data was analyzed separately and then corroboration given to emerging themes by comparing/discussing individual interpretations and highlighting areas of commonality. THE QUANTITATIVE METHOD The quantitative method involved the use of questionnaires to collect data from IT workers from April-June 2004. This involved the examination of the relative strength of the different career anchors identified from interviews. Out of the 500 questionnaires that were sent out 336 questionnaires (67.2%) were returned. The demographic profile of the respondent is presented in Table 2. “take in Table 2” The sample consisted of 360 skilled workers drawn from two main sources: 20 IT companies based in Lagos (157 respondents) and participants of an IT symposium which was held in Lagos (179 respondents). The questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section focused on assessing the career anchors of the respondents while the second section focused on demographic variables. The items that assessed career anchors were developed from the findings from the qualitative research. 8 However, some standard items from previous research by Schein (1978) were also modified and included. The items that were adopted from Schein’s study were those items that tested the factors that collaborated with the factors we identified in the current study (e.g., stability, challenge, lifestyle). The career anchor variables were measured on a five-point Likert Scale ranging from (1) “Of no importance/ Not at all true” to (5) “extremely important/completely true”. Each of the career anchors was represented and assessed by four items. The questionnaires were pilot tested on a sample of 10 IT workers in Nigeria for validation. A factor analysis (varimax rotation) was performed (using SPSS) to determine whether the six career anchors identified from the qualitative study were empirically distinct and independent from each other. The results of the factor analysis produced six factors which account for 78 percent of the variance. This suggests that a six-factor career anchor is appropriate for this study. Factors were interpreted where they have Eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and item loadings greater than 0.50 on the rotated matrix. Basically, the criteria that was used to identify and interpret factors was that a given item should load 0.50 or higher on a specific factor and have a loading no greater than 0.45 on other factors. The result of the principal component analysis is presented in Table 3. The pattern of loading confirms that the four items hypothesised to make up each career anchors loaded heavily on the anticipated factor. One exception was an item that was anticipated to load on being in charge but which ended up loading on the being stable anchor. This was the questionnaire item “I would only stay for a long time in an organisation if I am given the opportunity to manage human and other resources”. This item loaded more heavily on the “being stable” anchor and did not load up to 0.35 in any other anchor. The loading reflects some inclusion of stability into its meaning and content. Thus, it was incorporated into the items that form the being stable anchor. As a result, five items were used to examine the being stable anchor while three items where used to examine the being in charge anchor. To further validate the homogeneity/ internal reliability of the items within each anchor, their Cronbach’s alphas were calculated and results shows that all the scale reliabilities are above the 0.7 level which Cronbach (1951) suggest as acceptable for basic research (see Table 4). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the 9 relationships between demographic variables-age, gender, educational qualificationand the average scores of career anchors. The results of these analyses are discussed below. FINDINGS FROM THE QUALITATIVE DATA The findings from the semi-structured interviews revealed the existence of six career anchors or orientations. These were being stable (9 participants), being marketable (13 participants), being challenged (8 participants), being free (5 participants), being balanced (6 participants), and being in charge (8 participants). The orientational categories should not be viewed as representing different types of workers because some of the participants expressed strong interest in more than one career anchor. The characteristics of these six orientational categories are discussed below. The existence of multiple career anchors supports Fieldman and Bolino’s (1996) assertion that individuals are likely to have multiple important career and life goals. BEING MARKETABLE A number of the participants were primarily interested in continual learning and skill development in order to enhance future career opportunities and remain employable. This orientational category was labelled “being marketable”. Workers in this category were focussed on working for organisations that offer extensive IT training and skill development opportunities. They attributed this desire for marketability to the need to meet personal and extended family obligations and to a personal interest in being technically competent and knowledgeable. “If I continue developing my IT skills I’ll be constantly approached by headhunters and I will be able to earn more money to take care of my family responsibilities and social responsibilities in the village.”(Case 3) “The more I learn the more I’ll get paid, and the better I’ll be able to take care of my family...I always put into consideration the training and 10 development opportunities available in an organisation before taking up a job. The more training I get the more opportunities that will open for me and the more likely that I will be getting good jobs that will enable me meet my personal and family obligations.” (Case 8) Others wished to avoid IT skill obsolescence and to keep up to date with the skills that are recognised in the IT industry. “The dynamic nature of the IT industry in Nigeria demands that I keep up-todate with the latest technologies in my technical area. My primary consideration while taking any job has always been –will it extend my IT skill portfolio.” (Case 6) In sum, socio-cultural factors in the form of obligations to family and friends as well as rapid technological advances were key factors identified by IT workers in seeking the development of marketable skills. This may be reflective of the significance of the “new career” discussed earlier which characterised by increasing need for portable skills, knowledge and abilities across multiple firms (Arthur and Rousseau, 1996). BEING STABLE Some participants prioritised financial security over work content or rank in the organization. This orientational category was labelled “being stable”. The participants in this category considered the reputation of an organisation (e.g. to pay well, to pay reliably, to consider employee welfare) as the most important factor in their career decisions. Their desire for stability was related to the insecurity characteristic of the Nigerian economy. “You just never know what is going to happen. It’s hard enough finding a good job, why mess with something good when you have it? …..I accepted this job because this organisation has a solid work history of paying workers on time and keeping dedicated employees. They also offer pensions scheme if you work here for 10 years. With this I am covered and can take good care of family problems and look after my elderly parents in the village.” (Case 20) 11 “…I am only interested in working for well established companies that will offer me economic stability to enable me meet personal and family obligations.” (Case 25) “ …I was laid off by my former company and my family really struggled to survive because I am the breadwinner. I will never work for a company without a strong reputation. I don’t mind sacrificing high pay to get a lower paying job that is secured and reliable.” (Case 28) In sum, workers with the “being stable” career anchor were motivated by the desire for job security and for future stability. This can be linked to high levels of uncertainty within their economic and organizational contexts. BEING CHALLENGED Some of the participants were motivated by a desire for new challenge and for work using the latest technologies. This orientational category was labelled “being challenged”. These workers were keen to job hop to maximise the opportunities to work in challenging projects and were sometimes willing to sacrifice high pay. Some had rejected high paying jobs because of the mundane nature of the work involved on the grounds that such work would constrain their creativity and reduce their bargaining power in the industry in the event of a job loss. “Good pay and benefits can get me to take up a job, but will not generate the attitudinal commitment for me to remain in a company that does not offer challenging work assignments. If I had to do the same thing over and over again, I will quit.” (Case 6) “I don’t mind taking a job at lower pay levels to work on a cutting edge IT projects. I enjoy working in a challenging environment and keeping abreast with technological advances in my area.”(Case 8) “I will always prefer to move to any organisation that offers me variety in terms of challenging IT projects rather than committing myself to working in an organisation that offers no challenging IT project.” (Case 12) 12 Many of the workers in this group were activating a long term plan to enter the industry, having studied appropriate courses at university. This is unlike other categories of workers who often transferred to IT out of other areas in search of better economic circumstance. BEING BALANCED A number of participants expressed strong interest in balancing work and non-work commitments and were drawn to organizations that allowed this balance to take place. This orientational category was labelled “being balanced”. Preferred organizations that offered flexibility in the form of part time work, shift work, contract work and reduced hours. These workers were mostly women who expressed the importance attached to personal fulfilment, family and flexibility. “… Due to my past experience I always make a conscientious choice when selecting my career to choose a job that would allow me the opportunity to support my family. I will always want to be a good and supportive wife and mother for my husband and children.” (Case 9) “I do not joke with my family responsibilities. I have to give enough attention and care to my husband and children. That is very important to me.” (Case 1) “I find it difficult to take time away from work to take my child to hospital. My boss shows his displeasure anytime I have to go off. I do not want to stay here for a long time. I need to find a more conducive work environment that will enable me give enough time to my family.” (Case 10) Workers with the being balanced career motive accordingly sought career paths that were compatible with family and other non-work responsibilities. BEING FREE The primary career motive for some participants was to be on their own, work at their own pace and have a flexible schedule – rejecting externally imposed rules and 13 procedures. This career motive was labelled “being free”. These participants had an orientation towards becoming entrepreneurs. Their overriding career interest was the opportunity to be independent, to make their own decisions and to implement their own technical ideas. Some choose to work for other organisations in the short term to enable them to gain experience and to develop networks which would help them in establishing their own business. They accordingly, while in employment, scanned the environment for this opportunity. “I earnestly desire to be on my own and do things the way I want to without seeking approval.” (Case 30) “…I find my present organisation quite restrictive and I am seriously considering moving out to set up my own small IT consultancy firm. I particularly look forward to the sense of achievement that comes with setting up one’s own business and seeing it grow.” (Case 10) “… Being allowed to work on my own without interference is a key issue for me. It is the main reasons why I am thinking of leaving my present job to set up my own small company.”(Case 15) Workers with the being free career motive thus sought or were seeking career moves which allowed them to become entrepreneurial within the industry, rejecting the constraints (and boredom) of paid employment. BEING IN CHARGE Some participants were primarily interested in working for organisations that offered them the opportunity to manage people and other resources. This orientational category was labelled “being in charge”. The participants prioritised upward progressions and gained satisfaction from carrying out managerial activities. Their interest was to control, influence and supervise others towards achieving set tasks. “…..I enjoy the opportunity this organisation offers me to supervise large groups of people and I see myself still working for this organisation in the foreseeable future as long as I remain in charge.”(Case 25) 14 “……I want to be in front, I’ve always been in the backyard. They just remember you when the network is having problems. I want to be at the top where I can influence decisions and get recognised for my work.” (Case 20) “I have always wanted to be in a managerial position. I want the opportunity to manage different departments in the organisation in order to be able to manage any organisation.”(Case 17) IT workers interested in being in charge were concerned with maximising their chances for achieving promotions and with gaining power and responsibility within an organisation rather than specialising in a particular IT area. FINDINGS FROM THE QUANTITATIVE DATA As we have seen, six career anchors were identified in the first phase of the study. These were being stable, being marketable, being challenged, being free, being balanced, and being in charge. Given that a variety of career anchors were identified among the participants and a number of the participants expressed interest in more than one anchor, it was considered necessary to establish the career anchor that was dominant for this group of workers. The quantitative study enabled the strength of the identified anchors to be established. To this end, we followed the approach adopted by Igbaria et al’s (1995) similar study of the career orientations of IS employees in South Africa. This involved calculating the average score of each of the orientational categories. The mean scores are presented in Table 4. “take in Table 4” From the table it can be seen that being stable and being marketable are the most dominant anchors while being balanced is the lowest rated career motive. The possible reasons for the importance attached to the different career anchors are discussed below. There were some significant gender differences. Results showed that male workers have a higher orientation to being in charge than their female counterparts (4.05 vs. 3.75, F=12.9, p<0.05) while female workers have a higher orientation to being balanced (3.86 vs. 2.75, F=55.9, p<0.05). There was also a 15 significant difference in terms of age. Older workers (i.e. those over the age of 45) have a greater orientation to being in charge anchor (F=21.9, p<0.001) and to being balanced (F=16.3, p<0.001). There was no significant difference in career orientation by levels of educational qualification. DISCUSSION Drawing on institutional theory, which argues that societal context shapes behaviour and decisions, this paper set out to explore the career anchors of individuals in Nigeria and to assess their relative strength. Findings reveal four key issues. Firstly, in a departure from Schein’s work, a new career orientation “being marketable” emerged from the data. The interest in this anchor is largely based on the current economic realities in Nigeria which is characterised by high unemployment and wide variations in wages offered by organisations. This insecurity is heightened for this category of workers because of the absence of minimum wage legislation. Thus, individuals aspire to develop a portfolio of highly sought out skills in order to command sufficient income to meet their obligations. This supports Scott’s emphasis on the significance of a country’s regulative pillar for individual choices and decision making. Secondly, there was no evidence of one of the anchors identified by Schein - “service and dedication to a cause”. The absence of this anchor can be attributed to differences in the national context between Schein’s work and the current study. Drawing on Scott’s conceptualisation of the normative pillar as well as the cognitive pillar, economic insecurity and the role of family obligations may mean that individuals are more motivated by and “tuned into” instrumental factors that benefit themselves and their family over the pursuance of broader ideas that benefit wider society. This is in contrast to the West where people are interested in advancing social issues that address wider societal values. Thirdly, findings suggest some consistency between Schein and the current study in terms of five of the six anchors identified (being stable, being balanced, being challenged, being free, being in charge). However, the factors underlying the interest in these anchors are different and are context dependent. For example, the being in- 16 charge anchor reflects, in terms of Scott’s normative pillar, the primacy afforded to status and prestige (particularly for men) and the strong links these have with power in Nigeria. In essence, while there are some observed similarities between the anchors identified in this study and those proposed by Schein, underlying factors provide a distinct empirical contribution. Finally, the importance attached to these anchors is specific to the Nigerian context and thus are different from other work in the area. The most important orientations from the current study are being stable and being marketable. However, as noted earlier in this paper, previous studies have shown that challenge and service is the most dominant anchor in USA. Also, job security and service has been identified as the most dominant in Taiwan while lifestyle has been identified as the most dominant anchor in Israel. The high importance attached to being stable and being marketable career anchors can be related to the specific economic and cultural conditions in Nigeria. In terms of the stability anchor, economic uncertainty and the collectivist nature of Nigerian culture may well propel individuals to aspire to achieve stable economic circumstances in order to provide support to members of their internal and external family and also to meet their obligations. The strength of the stability anchor can also be attributed to the lack of a solid welfare system that can cushion the effect of job loss. In a similar vein, the strength of the “being marketable” anchor as noted above can be attributed to the need for marketable skills in an uncertain economic environment that will enable individuals to command sufficient income to meet their obligations. The being in charge anchor was the third most dominant orientation. As we have seen, the relatively high importance attached to this orientation may be due to the benefits (e.g. power advantage, high pay, prestige and social status) that can accrue from holding a high position of authority in Nigeria. These factors accrue mainly to older men in Nigerian society which explains the higher value placed on this anchor by male respondents as well as those in an older (45+) age bracket. At the other end of the scale, the low importance attached to “being challenged” is not surprising given that it may involve sacrificing pay in order to work on challenging projects. Given the 17 economic conditions in Nigeria, and drawing on Scott’s cognitive pillar, workers are more likely to be motivated by extrinsic factors (e.g. money) rather than intrinsic factors (e.g. job satisfaction). This is supported to some extent by Hofstede (1991) who found a bias in West Africa towards “masculine” values of competitiveness and materialism, where motivation is largely based on the acquisition of money and material possessions rather than on quality of life issues such as job satisfaction. The higher value placed by women on the being balanced career anchor, reflective of the priority given by women in Africa to quality of life issues as well as their traditional role as primary home makers (Igbaria et al, 1995), may support this view. Equally, the low importance given to the “being free” anchor may reflect current economic conditions characterised by high instability, high interest rates and lack of availability of venture capital - discouraging individuals from taking the risk of setting up their own company. The lowest rated career anchor was the “being balanced” orientation. Given the level of economic uncertainty and the more materialistic and “masculine” values inherent in Nigerian culture (Hofstede, 1991), economic success is a highly valued outcome. Many musicians, for example, eulogise the achievements of economically- successful individuals. A typical example is Oliver de Coque, a household name in the Nigerian music industry known for his heroic praise songs. It is therefore common for people to aspire to material wealth through hard work and the sacrifice of non-work activities. The focus on work rather than balancing work and non-work commitment suggest that the traditional proxies of assessing career success such as pay and promotion (Greenhaus, 2003) are still dominant in Nigeria unlike in the West where there is an increased interest in less tangible, subjective outcomes such as work-life balance (Feingold and Mohrman, 2001), as well as a sense of meaning (Wrzesniewski, 2002). CONCLUSION This paper set out to explore the career anchors of individuals in Nigeria, a region relatively neglected in the literature. Findings suggest the continued significance of 18 traditional orientations to careers in Nigeria (based around predictability and stability) as well as orientations associated with new career theory (the need for individuals to take responsibility for the update of their skills to enhance their marketability). The research has also highlighted the significance of contextual factors and supports the continuing relevance of Scott’s (2001) three institutional pillars. In this respect we have demonstrated the significance of the regulative pillar (e.g. through minimum wage regulations), the normative pillar (e.g. through the role of family obligations) and the cognitive pillar (e.g. through the priority given by individuals to instrumental values). Together these serve to shape the motivations and careers of individuals. Based on the findings of this study, we argue, along the lines of Thomas and Inkson (2006), that in order to better understand individual’s career needs, we must progress beyond the individualistic and decontextualised models offered by the majority of studies and develop a more complex interpretation, which acknowledges the interplay between individual careers and the wider institutional and national structures. This supports the view (e.g. Budhwar and Baruch, 2003) that dominant Anglo-Saxon assumptions about the nature of careers may not be applicable to other national contexts. In particular, the dominant view of the career as a “project of the self” (Grey, 1994) can be seen to be founded on Western based liberal democratic principles of the autonomous self, responsible only for his or her own actions and behaviours. This conceptualisation does not sit easily with collectivist orientations found in countries such as Nigeria where obligations to others shape and constrain individual choice. The practical implication of these findings is that HR managers in developing countries should be cautious of adopting career management models developed in the West where, as in the US, there is often a focus on the individual, on rights and on the need to preserve autonomy and independence (Schneider and Barsoux, 2003). This is likely to be out of step with the more collectivist orientation in developing countries such as Nigeria. The desire for stability and the burden of obligations may mean employees give preference to a reward system which minimises uncertainty and risk. At the same time, there may be a greater preference for financial incentives over non-financial incentives such as flexibility or holidays. 19 The extent to which the findings of this research can be generalized is constrained by the selected context of the research. The career anchor typology developed in this study, though tentative, can form the foundation for future research. A fruitful area of inquiry may be the relationship between career anchors identified in this research and external career outcomes, such as job satisfaction, motivation and retention, in Nigeria. This would provide invaluable information for the career management of IT workers in this context. REFERENCES Arthur, M.B. and Rousseau, D.M. (1996), The Boundaryless Career: A New Employment principle for a New Organisational Era, New York: Oxford University press. Baruch, Y. (2004), Managing Careers: theory and practice, Harlow: Prentice-Hall. Budhwar, P.S. and Baruch, Y. (2003) “Career management practices in India: an empirical study”, International Journal of Manpower, Vol 24 No 6, pp. 699-719 Counsell, D. (2002) “Careers in Ethiopia: An Exploration of Careerists’ Perceptions and Strategies”, Career Development International, Vol 4 No 1, pp. 46–52 Cronbach, L. J. (1951) “Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of test”, Psychometrica, Vol 16 No 3, pp. 297-334 Danziger, N. and Valency, R. (2006) “Career anchors: distribution and impact on job satisfaction, the Israel case”, Career Development International, Vol 11 No 4, pp. 293-303 Feldman, D.C. and Bolino, M. C. (1996) “Careers within Careers: Reconceptualising the Nature of Career Orientations and their Consequences”, Human Resource Management Review, Vol 6 No 2, pp. 89-112 Gattiker, U. E. and Larwood, L. (1988) “Predictors for managers’ career mobility, success and satisfaction”, Human Relations, Vol 41 No 8, pp.569–591 Ginzberg, M. J and Baroudi, J. J. (1992) “Career Orientations of I.S. Personnel”, Proceedings of the ACM SIGCPR Conference, April 5-7: 41-55. 20 Greenhaus, J. H. (2003), “Career dynamics”, In Borman, W., Ilgen, D. and R. Klimoski, R. (Ed.), Comprehensive Handbook of Psychology, Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New York: Wiley Grey, C. (1994) “Career as a Project of the Self and Labour Discipline”, Sociology, Vol 28 No 2, pp. 479-498 Hall, D. T. (1996), “Long live the career: a relational approach”, In Hall, D.T. (ed.), The career is dead, long live the career, San Francisco: Jossey Bass Hall, D. T. and Mirvis, P. (1996), “The new protean career”. In Hall, D.T. (ed.), The career is dead, long live the career. San Francisco: Jossey Bass Hall, D. T. (2002), Careers in and out of Organizations, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hofstede, G. (1991), Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind, New York: McGraw Hill. Igbaria, M., Greenhaus, J. H. and Parasuraman, S. (1991) “Career orientations of MIS employees: an empirical analysis”, MIS Quarterly, Vol 15 No 2, pp.151-69 Igbaria, M., Kassicieh, S. K. and Silver, M. (1999) “Career orientations and career success among research, and development and engineering professionals”, Journal of Engineering and technology Management, Vol 16 No 2 pp. 29-54 Igbaria, M., Meredith, G., Smith, D. C (1995) “Career Orientations of Information-Systems Employees in South-Africa”, International Journal of Strategic Systems, Vol 4 No 4, pp. 319-340 Igbaria, M. and McCloskey, D.W. (1996) “Career orientations of MIS employees in Taiwan”, Computer Personnel, Vol 17 No 2, pp. 3-24 Ituma, A. N. and Simpson, R. (2006) “The Chameleon Career: An Exploratory Study of the Work Biography of Information Technology Workers in Nigeria”, Career Development International, Vol I No 2, pp 48-65 Kim, N. (2004) “Career success orientation of Korean women bank employees”, Career Development International, Vol 9 No 6, pp. 595-608 Nicholson, N. (2000) “Motivation-Selection-Connection: An Evolutionary Model of Career Development”. In Goffee, R .E and Peiperl, M.A (Ed.), Career Frontiers: New Conceptions of Working Lives, New York: Oxford University Press 21 Ovadje, F. and Ankomah, A. (2001) “Human resource management in Nigeria”, In Budhwar, P. S. and Debrah, Y. A (Ed.), Human Resource Management in Developing Countries. London: Rutledge. Petroni, A. (2000) “Strategic career development for R and D staff: a field research”, MCB Team Performance Management: An International Journal, Vol 6 No ¾, pp.1-12 Pringle, J. K., and Mallon, M. (2003), “Challenges for the Boundaryless Career Odyssey”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol 14 No 5, pp. 839-853 Schein, E. (1984), “Culture as an environmental context for careers”, Journal of occupational behaviour, Vol. 5, pp. 71-81 Schein, E. (1986), Organizational Culture and Leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers. Schein, E. (1978), Career Dynamics: Matching individual and organisational needs. Reading, Mass: Addison Wesley. Schein, E. H. (1987), “Individuals and Careers”, In Lorsch, J. (Ed.) Handbook of Organisational Behaviour, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Schein, E. H. (1990) Career Anchors: Discovering Your Real Values. San Diego, CA: Pfeiffer and Company. Schneider, S. and Barsoux, J. (2003), Managing Across Cultures, Prentice-Hall. Scott, R. (2004), “Institutional Theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program” in Ken, G., Michael, A. (Eds.), Great Minds in Management: The process of Theory Development Sparrow, P. and Hiltrop, J.M. (1996), European Human Resource Management in Transition, London: Prentice. Strauss, A. and Corbin, J. (1990), Basics of qualitative research, Newbury Park, CA: Sage publications. Thomas, D. C and Inkson, K. (2006), “Careers across Cultures” In Gunz, H. and Peiperl, M. (Eds.), Handbook of Career Studies. New York: Sage Publications. In Press World Bank (1997), The World Bank Annual Development Report Wrzesniewski, A. (2002) “It's not just a job: Shifting meanings of work in the wake of 9/11”, Journal of Management Inquiry, Vol 1 No 2, pp. 230-235 22 APPENDIX Table 1: Interview protocol The interview protocol consisted of the following (repeated) series of questions The interview also contained questions dealing with overall career goals and life plans. These included: (1)What was your next major change in job or organisation 1) As you look over your career and life so far, can you describe some times that you especially enjoyed (did not enjoy) and what made them enjoyable (not enjoyable)? (2) How did this come about? What motivated the change? (2) As you look ahead in your career, what things do you look forward to (want to avoid)? (3) How did you feel about the change? How did it relate to your goals? (3) What is the most important career need that you will not give up when forced to make a career decision? Table 2: Demographic Profile of the respondents FREQUENCY PERCENTAGE GENDER Male Female 233 103 69 31 AGE 18-25 26-35 36-45 45 and above 33 172 103 24 9 51 31 7 Education Primary Secondary Diploma Bachelors Masters Doctorate 1 16 27 200 85 5 .3 5 8 60 25 1.5 23 Table 3 - Rotated Factor Matrix Questionnaire Items (Variables) Factor 1 Being Challenged Factor2 Being Free Factor 3 Being Marketable Factor4 Being Balanced Factor5 Being Stable I will feel successful in my career only if I face and overcome very difficult technical challenges…. I feel very fulfilled in my career when I have solved seemingly unsolvable technical problem An endless variety of technical challenges in my career is what I really want Working on challenging technical problems that are almost unsolvable is…. I would rather leave my organisation than accept a job that would reduce my autonomy and freedom I am most fulfilled in my work when I am completely free to define my own tasks, schedules and procedures The chance to do a job my own way, free of rules and constraints, is more important to me than any other factor I will feel successful in my career only if I achieve complete freedom to pursue an implement my technical ideas I always seek to develop marketable skills and knowledge that will boost my employment prospects outside my present organisation A job that provides the opportunity for an individual to continuously develop marketable technical skills is I would not accept a job that will not offer me the opportunity of improving and extending my marketable technical skill base I seek to develop marketable technical skills from the job situations I experience to enable me get another job easily I dream of a career that will permit me to integrate my personal, family and work needs I would rather leave my organization than to be put into a job that would compromise my ability to pursue personal/family concerns Balancing the demands of personal and professional life is more important to me in my career than any other factor I will feel successful in life only if I have been able to balance my personal, family and career requirements I dream of having a career that will allow me feel a sense of security and stability I only seek for jobs in organisations that can offer me employment security I will feel very satisfied in my career when I have guaranteed employment stability An organization that will provide me stability through guaranteed work, a good retirement program, etc. is. The process of supervising influencing, leading, and controlling people at all levels is I will feel successful in my career only if I attain a managerial position in an organisation To be in a position of leadership and influence is I would only stay for a long time in an organisation if I am given the opportunity to manage human and other resources 0.892 0.170 0.020 0.012 0.022 Factor6 Being in charge 0.000 0.853 0.150 0.021 0.014 0.021 0.102 0.841 0.120 -0.019 -0.001 -0.022 0.112 0.794 0.140 0.215 0.014 -0.012 0.002 0.185 0.860 -0.228 0.110 -0.184 0.021 0.170 0.843 -0.177 0.111 0.132 0.209 0..241 0.795 -0.282 0.104 0.180 0.137 0..208 0.785 -0.003 0.203 0.124 0.221 0..205 0.215 0.835 -0.112 .0216 0.012 0..350 0.029 0.792 0.204 0.125 0.274 0..240 0.105 0.755 0.307 0.198 0.227 -0.010 0.023 0.706 0.275 0.204 -0.050 0.172 0.008 0.210 0.810 0.266 0.075 0.256 0.020 0.385 0.760 0.121 -0.014 -0.178 -0.010 0.171 0.712 0.147 0.306 -0.140 0.010 -0.087 0.682 0.296 0.164 -0.016 0.012 -0.035 0.430 0.780 0.069 -0.110 -0.001 -0.161 0.120 0.753 -0.112 -0.158 -0.021 -0.212 0.304 0.694 0.072 0.051 -0.022 -0.012 0.123 0.653 0.175 0.285 -0.034 0.012 0.116 0.031 0.730 0.020 -0.024 0.022 0.016 0.032 0.680 0.041 -0.131 0.021 -0.001 -0.012 0.658 0.180 -0.029 0.012 0.014 0..576 0..325 (Shaded items are those included in calculation of factor score) 24 Table 4- Mean Scores and Cronbach Alphas Career Anchors Being Being Being Being Being Being free in charge marketable challenged stable balanced Mean 3.85 3.96 4.07 3.89 4.18 3.09 Ranking 5 3 2 4 1 6 Cronbach Alpha .83 .71 .73 .78 .81 .76 25