Planning Your Career

Planning Your Career

Barbara Worembrand asks: are you prepared?

Organisations are changing as they become increasingly unstable because of the rapid growth of technology and globalisation. Moreover, the economic markets are expanding and the changes being made are quite extensive, both politically and socially. In addition, there are pressures on the organisation to change, adapt and grow. All of this is having a tremendous impact on the trends in careers, career planning and the role of the individual employee. Current trends in legal careers include the following:

For individuals, an increasing workload

For organisations, structural change: a flattened hierarchy, the elimination of management layers and a reduction in the number of people employed

Mor e global competition: organisations are now required to make maximum use of employee’s skills, aptitudes and potential

More team-based work: a shift from distinct and separate functions to joint work on a specific project or the development of new products

More shortterm contracts: the length of the person’s employment is known at the outset and contract renewal is sometimes uncertain

Increasingly frequent change in the nature of the skills required in the workplace because of new technology and other factors

More part-time jobs

Changing composition of the work force: due to relatively low birth rates and increasing longevity of employees. In addition, greater diversity in terms of ethnicity, gender and values

More self-employment and employment in small organisations

Working at or from home

Legal careers are becoming more complex and the context is changing. Individual employees must:

Look ahead and keep updating their skills and knowledge to remain “employable”. Do not rely on the organisation to do it for you! You need to be proactive. Once, solicitors were able to rely on their legal expertise alone. Now they must also exhibit business acumen, financial awareness, intercultural sensitivity and self-marketing techniques for fee generation. Learning is a life-long process!

Make a real and consistent effort to build up and maintain networks of contacts (business, academic, social, professional)

Realise more effective skills of entrepreneurship and self-management (even in larger organisations)

Be ready to handle uncertainty and change and be more flexible in terms of your relationship with other people

Careers are more varied, and boundary-less, in that, either by choice or necessity, people now move across boundaries between organisations, departments, hierarchical levels, functions and sets of skills and potential. Careers are becoming more like short-term episodes.

In relation to the changing nature of legal careers there is the emergence of the “psychological contract”.

This represents the informal, unwritten understandings between the employer and employee. It means that the employee usually offers longer hours, broader skills, and tolerance of change and ambiguity and a willingness to take on more responsibility. In return the employer offers (to some) high pay, rewards for high performance and simply – a job!

For legal professionals, executives or students, the current situation will strongly impact on their career choices, in that the degree of introspection and self-assessment necessary to effect career planning is stronger that ever before, if they are to successfully avoid “career chaos”.

Career planning involves one’s whole life, not just an occupation. It concerns the whole person, their needs, wants, capabilities, potential, excitements, anxieties, insights and blind spots, warts and all. It concerns the individual in the changing context of his or her life. This includes aspects such as

- Environmental pressures and constraints

- Relationships with significant others

Essentially, career development and personal development converge. Self-awareness is crucial and one needs to have an accurate appraisal of his or her own strengths and weaknesses, values, personality and vocational interests.

A knowledge of legal careers is also imperative. Self-knowledge and occupational knowledge need to be aligned. For example: am I more suited to Media Law or Criminal Law? Do I want to work in-house or on my own? For the public or private sector? And so on. Decisions as to the above-mentioned are made logically and systematically, or by “gut instinct” – or dependently; waiting, in other words, to see what circumstances dictate. The latter is the least effective strategy!

Personal objectives are often partly based on the developmental stages relating to a n individual’s increasing age. These transitions are typified by certain internal struggles (and resolutions) before one can move effectively into the next stage – “Phases of Development” in adulthood. (Eriksen, Levinson)

Four career stages identified by Donald Super (1957) include:

1. Exploration of both self and the world of work in order to clarify the self-concept; and identification of occupations which fit it. Typical ages

15-24

2. Establishment: perhaps after one or two false starts, the person finds a career and makes efforts to prove his or her worth in it. Typical ages 25-44

3. Maintenance: the concern now is to hold onto the niche one has carved out for oneself. This can be a considerable task, especially in the face of technological changes and vigorous competition from younger employees. Typical ages 44-65

4. Disengagement: characterised by decreasing involvement in work: a tendency become an observer rather than a participant. Typical ages 65+

Sometimes individual needs are seen as the most important aspect of career planning – for instance, in terms of changing personal motivations, or the need for achievement, and so on. Also important are sociological factors – such as socio-economic factors, home, school and community – and not necessarily an individual’s personality or abilities. One can assess, for example:

The impact of

1) My parent’s career expectations (implicit or not)

2) My siblings’ careers and expectations

3) My first influential teacher

4) My first influential boss/job

5) The best/worst role models

6) My partner’s career and expectations

7) My peer group

Often a dramatic change in one’s life precipitates self-exploration, which also brings one’s career into focus.

Examples include marriage, divorce, death, moving home or a new job. Personal development faces a disruption especially if unplanned.

The loss of self-direction or control and the resultant stress influences daily coping and affects everything to do with our careers and job performance and satisfaction. Often a compl ete reassessment of one’s career interests and values then becomes inevitable. Issues that subsequently become apparent often include career choice, the nature of the work itself, personal success, career progression and the possibility of advancement, and one’s “quality of life” in general.

As mentioned, continuous self-assessment of interests, purpose, values, aptitudes and paths to guarantee marketability (Continuous Personal Development) are always of great consequence! Changing a job, career or role involves preparation (self-marketing, effective information seeking, and self-assessment) and adjustment. In fact, transitions at the start and the end of working life are for most people less difficult than often assumed.

So, where does one actually begin? And how does one start in practice?

Firstly, one should consider one’s vocational preferences. For example: Am I drawn to the “welfare” types of professions, i.e. is it important for me to help the emotionally, physically or economically disadvantaged? If so, then you would be more attracted to such areas of law as Personal Injury, Criminal Law, Human Rights

Law or Immigration Law, regardless of what your profession is within the law (solicitors or paralegals, for example).

Do I find “persuasive” careers attractive? Do I need to influence the feelings, actions, behaviour and thoughts of other people or events? If so, then you might find International Corporate Law or Commercial

Property Law the most appealing.

If you find the “administrative” type of careers appealing then you are more attracted to those specialisms which are paper –driven, data–orientated and procedural by nature. Administrative Law, Tax Law, Financial

Services, Wills, Probate and Trusts are probably your passion!

Affinity with the “creative” professions would suggest a bias towards Media Law or Intellectual Property, whereas “scientific” or “engineering” preferences perhaps predispose one to Environment or Planning Law.

Are they consistent with what you felt five years ago, for example? If not, why not, and what has changed?

Secondly, an assessment of one’s aptitudes may be necessary. Do you easily solve new problems from logic or first principles? Do you need training on a task? Could you be thrown in at the deep end? Are you a multi-tasker? Do you need cerebral challenge? One could expect that those studying law or in the profession would have a high level of verbal abstract reasoning; have, in other words, an ability to develop strong skills in reading, writing and communication. Would this be a struggle? Are you actually more numerate, for example? which would suggest that Accountancy Law is a more appropriate option in terms of your inherent

(if not acquired) strengths. If verbal reasoning is not your strongest aptitude, how important will it be to develop it? In such a situation, Forensic Accounting as a career option would certainly mean less stress.

Thirdly, how would you describe your temperament or personality (which does not alter significantly)? For example:

- Are you an introvert or an extrovert? Would you rather work behind the scenes with ideas and concepts, or with people?

- Do you need the camaraderie and support provided by working in a team or do you prefer small groups and one-to-one relationships?

- How prone are you to stress? How effectively do you cope? Do you have the emotional and physical resilience to put in a twelve-hour day or to become self-employed?

- How assertive are you? Can you confront conflicts or argue your legal standpoint at the Bar?

- Do you need autonomy? Do you need to devise the system and policies yourself, or do you need to follow

“preordained” organisational rules – and need to know exactly what is expected of you?

- How effectively can you deal with office politics (which some may see as inevitable to working life!)? Are you vigilant or highly trusting? Are you a private person or very forthright in your formal or informal interactions with others?

- Are you imaginative or practical? Are you known for your novel ideas or for the effective implementation of them?

- How is your self-confidence? Do you reproach yourself, or have a high self-esteem? Will you be confident enough to articulate your views or give presentations, both within the office and to new clients?

- Are you traditional or more open to change? If you are traditional, you will be happier in a large organisation which is more hierarchical, bureaucratic and staid than if you are change-oriented. In the latter case, working in a small to medium-sized company, being more dynamic and flexible, might be more suitable. You might also be more entrepreneurial and better suited to going self-employed (or in providing contract work) at some stage in your career.

- How self-disciplined are you? Do you tolerate disorder? Do you meet deadlines at the last minute or do you plan ahead? Do you have the tenacity and perseverance to tackle the more mundane aspects of your study or your job? Are you highly conscientious and rule-bound or non-conforming?

- Do you have leadership potential? You may be successful but can you manage others to achieve? Can you build self-empowered teams? (Can professionals be successful managers?) Do you want to manage people?

What do you want to develop? Is it necessary to develop it for your studies, your job or yourself? Selfdevelopment is coached through mentoring, often by professionals.

Finally, think about your values. Are they actually in contradiction with reality? For example:

- Are you seeking high financial remuneration, but plan to work primarily with Legal Aid clients? For example, how important is it to you to have a career, which is ego-driven or highly visible? Is that possible if you are seeking a more effective work/life balance, if you are planning to work less at the office?

- Are you ambitious, competitive and driven? Or would you prefer a more cooperative and less competitive type of organisational culture (would you rather work for Linklaters and Paines or in local government)?

- Would you rather be an expert or a leader? (or both?)

A similar and wellknown method of addressing career planning is to evaluate one’s individual career anchors. Edgar Schein (1993) has used some research he carried out many years earlier to develop the concept of career anchors. This has become very popular in recent y ears. Schein defined a person’s career anchor as an area of the self-concept that is so central that he or she would not give it up even if forced to make a difficult choice. He felt that people’s anchors develop and become clear during their early career, as a result of experience and learning from it. Schein’s list of alternative anchors people hold is as follows. One could look at the list of anchors and feel that several or even all of them are important, but which would win if one had to choose? That is the real anchor. Career anchors consist of a mixture of abilities, motives, needs, and values. They therefore reflect quite deep and far-reaching aspects of the person. It is perhaps the career anchor that a person questions when he or she is in the transitional period relating to careers.

Schein’s career anchors can be described by type as follows:

1. Managerial competence. People with this anchor are chiefly concerned with managing others. They wish to be generalists, and they regard specialist posts purely as a short-term means of gaining some relevant experience. Advancement, responsibility, leadership and income are all important. Are you a generalist?

2. Technical or functional competence. These people are keen to develop and maintain specialist skills and knowledge in their area of expertise. They build their identity and around the content of their work. Are you a specialist?

3. Security. People with a security anchor are chiefly concerned with a predictable work environment. This may be reflected in security of tenure (having a job) or in security of location (wanting to stay in a particular town, for example).

4. Autonomy and independence. These people wish most of all to be free of restrictions on their work activities. They refuse to be bound by rules, set hours, dress codes and so on.

5. Entrepreneurial creativity. Here people are most concerned to create products, services and organisations of their own.

6. Pure challenge. This anchor emphasises winning against strong competition or apparently insurmountable obstacles.

7. Service or dedication. This anchor reflects the wish to have work which expresses social, political, religious or other values that are important to the individual concerned, preferably in organisations that also reflect those values.

8. Lifestyle integration. People who hold this anchor wish most of all to maintain a balance between work, family, leisure and other activities, so that none is sacrificed for the sake of another.

Career counselling can be very helpful in developing an integrated long, medium and short-term (academic and professional) career strategy. Psychometric testing can be used to assess aptitudes, personality, attitudes, vocational interests and “emotional intelligence”, for example. Occupational psychologists can interpret this objective data and facilitate the individual’s efforts to clarify their perceptions of themselves and their world of work. A plan of action emerges when developed with an independent consultant (with no stake in the organisation or university) and provides a powerful set of tools for information and planning. There may also be gender differences when planning one’s career.

One way in which women have traditionally differed from men is, of course, the likelihood of being interrupted by child-bearing and child-rearing, and by the fact that in most households a woman does more of the childcare and housework than a man (no matter what her employment situation or status)! The presence of two people in a household, both pursuing careers (us ually called “dual-career couples”) adds extra stresses on both partners, but again these seem to fall more on the woman than on the man.

Women may prefer flexible working hours, such as total annual working hours which people can distribute through the year as they wish (within certain fairly broad limits). Career breaks have been used relatively extensively, most notably by financial services organisations. People can suspend their career with an organisation for several years, normally in order to make a start on raising a family. During that time one usually reports for refresher training for a small number of weeks per year. Academically, as well, women may also prefer more flexible options such as distance learning.

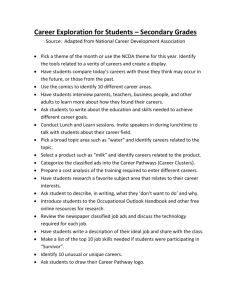

If one is still a student, work experience and vacation placements are becoming increasingly important when planning one’s career. Gain this experience wherever possible – even though there is fierce competition!

Moreover, the CV needs to show additional skills and experience, possibly demonstrated by voluntary work, extra-curricular activities, travel or leisure interests. Whether you are currently studying, training in your career or are established, your CV always has to be performance-driven and achievement-based. It should not read as a job description, but should state your concrete qualitative and quantitative positive results. As you are expected to be highly verbally skilled in your chosen career there is no excuse!

Ability to perform effectively at interviews is also essential. It would appear to be ludicrous to memorise one’s achievements on the CV – but it is essential. One has to master the verbal and non-verbal techniques of “positive” interviewing. How many highly talented legal professionals have not been offered articled clerk positions because they could not “sell” themselves verbally or non-verbally, even if their academic results were superb?

There are alternative careers for those in the law, for instance in law-related employment. They include: administration (usually in the public sector), analysis and research (legal publishing, information management and librarianship), community advisory work (probation work, housing management), teaching

(further and higher education, training for Further Education Certificate of Education) and commercial management (banking, accountancy, insurance, personnel or purchasing management).

When planning your career – gain marketable experience!

This is especially relevant for those individuals prior to commencing the legal practice course or the Bar

Vocational course.

Opportunities include:

- Barrister’s Clerk

- Voluntary work (Law Centre, Citizens Advice Bureau or organisations Dealing with Civil Liberties, Housing and so on)

- Legal Executive (does not have to be a short-term alternative)

- Licensed Conveyancer

- Postgraduate Law (in the UK or abroad)

- European Commission

“Stages” – placements for administrators and lawyers-linguists in the European Parliament and Courts of

Justice – 4 to 6 months.

The message conveyed in this article is simple: plan ahead!!

Career planning in the twenty-first century means that you have to continuously assess yourself on your vocational interests, aptitudes, values, personality and personal ambitions. Ponder your personal circumstances and ensure that your knowledge about the legal (or alternative) professions remains current.

Speak to friends, colleagues, professors or family members in the professions to learn more about the realities of these jobs. Since there is no ‘job for life’ any more, develop and maintain a powerful CV. Be economically irresistible in the job market!

Other aspects – such as your age, socio-economic factors, personal issues, gender, and the number of years (or months) you have spent in the profession, or studying, are also significant to the decision-making process. (Ethnic differences are not discussed in this article).

Should you be working in the legal profession already, take the initiative; be headhunted in your own firm!

Be prepared for organisational change and realise its eventual impact on your career planning both in the short- and the long-term. Develop your strengths and improve your weaknesses. Use and apply your unique potential, take control of your career and your life! Finally, remember the following quotation:

“Once while walking through and old graveyard, I came upon a tombstone with the epitaph: “Here lies one who was born a man and died a grocer.”

I realise now that my function is to prevent people from becoming merely grocers by helping them become aware of the relationship between their inner lives and their professional aspirations. To be blind to personal needs, and not to plan for them, leads to an ineffable sense of diminishment in one’s occupation. Yet, to rely heavily upon on occupation to meet personal needs, as if being a grocer could satisfy the whole person, is equally dangerous.” Mark L. Byers, “Becoming a Lawyer . . . and a Person”, Harvard Law School Yearbook,

1980.

Mr Byers is a lawyer . . . and a psychologist.

So. Does another career option beckon?