13. The American Revolution

advertisement

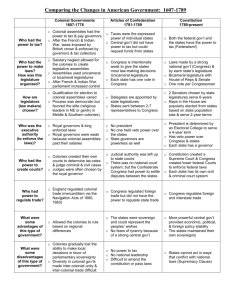

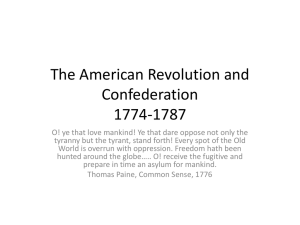

The American Revolution The 1774 Coercive Acts sparked open rebellion. Informal government associations sprang up in colonial America to take on the duties of not only running a peacetime government but also to prepare to defend their homes. This impulse to preserve self-government as the British took it away culminated in the First Continental Congress that convened in September of 1774. Fifty-five delegates from twelve colonies came (all save Georgia). Some of the greats appeared: Sam and John Adams, cousins from Massachusetts; “Give-me-liberty-or-give-me-death!” Patrick Henry; and a key person of whom you might never have heard, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. The Congress agreed to formally resist the Coercive Acts, and supplies were sent from other colonies to relieve the suffering of blockaded Boston. Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania proposed union between the thirteen colonies and Great Britain under new organization including a colonial government similar to what had been suggested under the Albany Plan of Union. The measure failed by the vote of one colony. The new inclination to centralize did establish the Continental Association to coordinate the efforts of the various informal associations to produce a continent-wide boycott. Colonists took non-importation pledges and non-exportation pledges and non-consumption pledges. The Continental Association openly encouraged persecution of those who broke boycotts. That dynamic brings us to assess the bad and the good of the American Revolution which was under way long before the War for Independence. A new political order emerged with mobs going through the streets searching for “enemies of the people,” and when they found them they weren’t nice to them. Upper classes in the colonies exploited popular resentment of England to gain personal power and influence. But on the bright side, there was a surge of popular interest in politics without which the formation of the United States of America would have been impossible. The ideas of no taxation without representation, for example, were applied to colonial legislatures, too, as middle class artisans demanded to be represented in government. This move broke the monopoly of government by the rich. Once in power, these new leaders pushed for practical political reforms like expanded suffrage (voting rights), secret ballot as opposed to oral voting, open meetings of legislatures (attended by the public, especially journalists), printing of the minutes of meetings, and publication of votes by representatives. All of these reforms enlarged the political arena and limited the power of office holders. Finally, a phenomenon hard to designate good or bad, politics came to be seen as the route to a better world. One could say this is a faulty premise, but it is the natural fallout of the American Revolution and remains a part of our identity. Together, these developments meant a new era was on the horizon. They caused Americans to divide into three groups: patriots, loyalists, and bystanders. Patriots and loyalists were each about 20% of the population and competed for the 60% of the population who had not committed to either side. As 1775 dawned, Great Britain was making military preparations. Lord North, however, attempted reconciliation by announcing that any colony voluntarily contributing to defense would be exempt from taxation. Colonists perceived this as a ruse to divide them since Parliament ignored the statements of the First Continental Congress. All colonies rejected North’s plan, and Britain was set on a military response. King George told Lord North, “Blows must decide whether they are to be subject to the country or independent.” In Massachusetts in April of 1775, General Gage ordered the arrest of what he thought were a bunch of amateur rabble-rousers assembled on Concord Green. When the troops appeared on the green, an anonymous shot was fired that ignited the first clash, a shot Ralph Waldo Emerson would later say was, “heard around the world.” The colonial militia were amateurs but sent the British packing back to Boston. All the way back past Lexington to the safety of their lines, redcoats were picked off from unseen fire from the woods surrounding the road. 273 British soldiers were killed with a loss of 95 patriots dead. By May of 1775, these dire circumstances caused the formation of the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. John Dickinson of Pennsylvania urged reconciliation. The new Congress passed his Olive Branch Petition in which America pledged loyalty to the king if he would break with his corrupt ministers. The Congress simultaneously passed the Declaration of the Causes and Necessities of Taking Up Arms, a document written by Dickinson and a young delegate from Virginia, Thomas Jefferson. This Declaration specifically denied independence was their goal. The necessity of taking up arms was merely for defense. They did list grievances, however. Meanwhile, another battle broke out on Breed’s Hill which was mistaken for Bunker Hill in June of 1775. The British commander, John Burgoyne, assumed the colonial rabble could not stand against British regulars and launched frontal assaults. The British eventually dislodged the militiamen, but only after the patriots ran out of ammunition. The deadly effect of American marksmen was famously enhanced by Israel Putnam’s order, “Don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes!” The cost of Burgoyne’s arrogance was 1,000 British casualties, 40% of his force. This first true battle of the War for Independence saw the heaviest losses of the war for the British. The Second Continental Congress heard the news and assumed central control of the colonies. Congress immediately created the Continental Army and appointed George Washington, one of the Virginia delegates and French and Indian War hero, as its commander. The Congress also issued paper money with which to pay troops and formed a committee to negotiate with foreign powers to seek alliances. On August 23, 1775, King George III ignored the Olive Branch Petition and declared the colonies in open rebellion. By October, he accused them of aiming at independence. By December, he declared all American shipping fair game for the Royal Navy to hunt and kill. In the winter of 1775-1776, colonial armies under Richard Montgomery and Benedict Arnold invaded Canada, hoping to incite Canadians to rebel, too. They were entirely unsuccessful except in learning that one should not invade Canada in the winter. Still there was no formal decision on the part of the Continental Congress for independence. Then, a school teacher came to the rescue. Thomas Paine published a lengthy pamphlet called “Common Sense,” in which he called King George a “Royal Brute” and openly called for independence from Great Britain. “Common Sense” went through 25 printings in 1776, alone. Interestingly, this piece of revolutionary propaganda was not a stylized work like Congress’s publications. Paine did not quote classical literature to show off his learning. He appealed directly to the masses and quoted only from the Bible. The sense of “Common Sense” is expressed in two ideas. Paine said kings by their very nature are evil, and a little island like Great Britain should not rule a giant continent like North America. Congress did two things. They opened American ports to the whole world in the spring of 1776, and by summer formally approved the Declaration of Independence. This document was written by a committee rather than just by Thomas Jefferson, and it clearly stated Enlightenment ideals while honoring the American traditions of autonomy under the sway of a divine being. When asked why such a document was necessary, Jefferson replied, “To place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent.” Instantly, the American Revolution was given universal appeal in the struggle for the natural rights of man. Why is this monograph shorter than usual? Because you are going to read the Declaration of Independence if I have anything to say about it, just as George Washington had it read aloud to his troops. Read, and remember. Sadly, most Americans today have never read it, nor can they distinguish it from the Constitution written thirteen years later.