History 352 - University of Puget Sound

advertisement

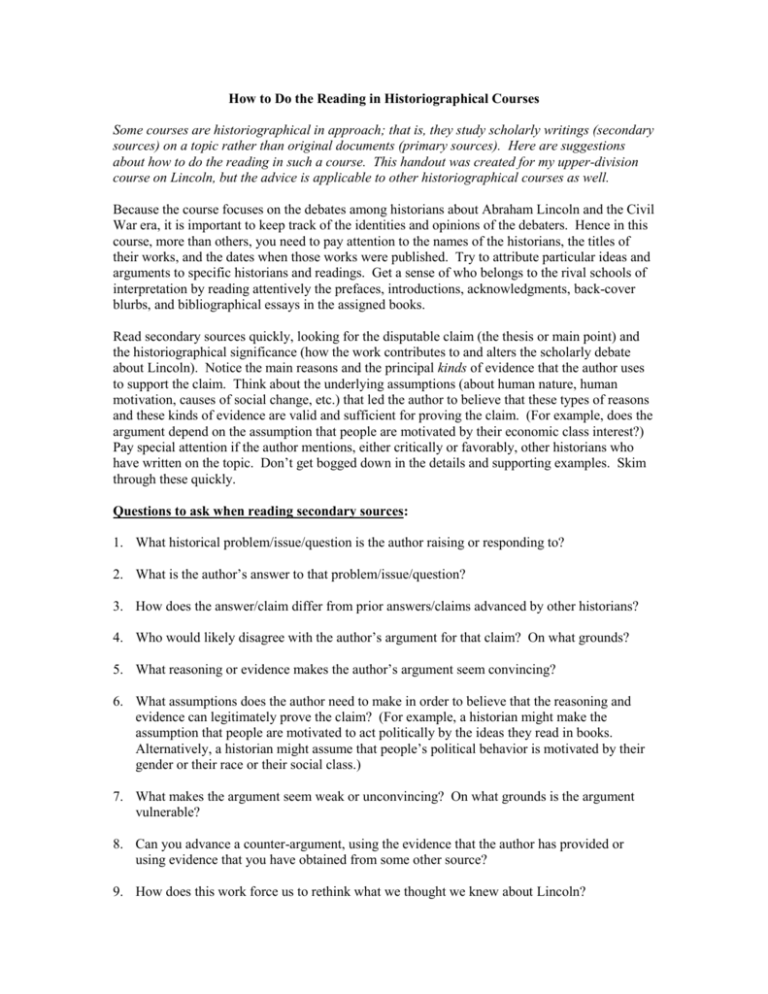

How to Do the Reading in Historiographical Courses Some courses are historiographical in approach; that is, they study scholarly writings (secondary sources) on a topic rather than original documents (primary sources). Here are suggestions about how to do the reading in such a course. This handout was created for my upper-division course on Lincoln, but the advice is applicable to other historiographical courses as well. Because the course focuses on the debates among historians about Abraham Lincoln and the Civil War era, it is important to keep track of the identities and opinions of the debaters. Hence in this course, more than others, you need to pay attention to the names of the historians, the titles of their works, and the dates when those works were published. Try to attribute particular ideas and arguments to specific historians and readings. Get a sense of who belongs to the rival schools of interpretation by reading attentively the prefaces, introductions, acknowledgments, back-cover blurbs, and bibliographical essays in the assigned books. Read secondary sources quickly, looking for the disputable claim (the thesis or main point) and the historiographical significance (how the work contributes to and alters the scholarly debate about Lincoln). Notice the main reasons and the principal kinds of evidence that the author uses to support the claim. Think about the underlying assumptions (about human nature, human motivation, causes of social change, etc.) that led the author to believe that these types of reasons and these kinds of evidence are valid and sufficient for proving the claim. (For example, does the argument depend on the assumption that people are motivated by their economic class interest?) Pay special attention if the author mentions, either critically or favorably, other historians who have written on the topic. Don’t get bogged down in the details and supporting examples. Skim through these quickly. Questions to ask when reading secondary sources: 1. What historical problem/issue/question is the author raising or responding to? 2. What is the author’s answer to that problem/issue/question? 3. How does the answer/claim differ from prior answers/claims advanced by other historians? 4. Who would likely disagree with the author’s argument for that claim? On what grounds? 5. What reasoning or evidence makes the author’s argument seem convincing? 6. What assumptions does the author need to make in order to believe that the reasoning and evidence can legitimately prove the claim? (For example, a historian might make the assumption that people are motivated to act politically by the ideas they read in books. Alternatively, a historian might assume that people’s political behavior is motivated by their gender or their race or their social class.) 7. What makes the argument seem weak or unconvincing? On what grounds is the argument vulnerable? 8. Can you advance a counter-argument, using the evidence that the author has provided or using evidence that you have obtained from some other source? 9. How does this work force us to rethink what we thought we knew about Lincoln?