Roundtable on gender

advertisement

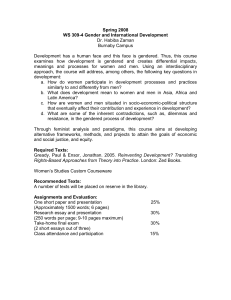

15th EACS conference, Heidelberg 2004. Roundtable discussion Teaching Gender: Approaches and Methods for Introducing Gender into the Curriculum on China. Anne Gerritsen (University of Warwick, UK), organizer and discussant, Naomi Standen (University of Newcastle, UK), discussant, Denise Gimpel (University of Copenhagen, Denmark), discussant, Birgit Haese (Technische Universität Dresden, Germany), discussant. Below is a brief summary of the discussion held at this ‘roundtable’. It only highlights some of the main observations, and doesn’t attempt to give a complete representation of the discussions. If you have any comments on this summary, please submit them to the WAGNet listserv (wagnet@listserv.warwick.ac.uk ) Anne Gerritsen opened the session and welcomed everyone present. She explained the aims of the discussion: to place next to each other several approaches to integrating women and gender into our teaching on China, and to evaluate these different approaches critically. Anne Gerritsen highlighted questions related to three topics in advance of the discussion. 1. The issue of theory. Is it possible to use gender as a category of analysis without providing at least some gender-related theory? Can we justify the decision to support our teaching in, say, a general historical overview module on Chinese history with theoretical materials about gender if we are already hard-pressed to cover all of the main topics, and if we ask our students to read more materials in a language that is not their own (i.e. English for non-English speakers). If we feel that teaching about China from a gendered perspective should be about more than merely documenting the experiences of women in China’s past, then we should perhaps be more explicit to our students about the ways in which this gendered perspective changes the story of Chinese history as a whole, or perhaps changes the periodization of Chinese history. 2. The issue of masculinity. We all agree that gender is about men and women, and some very interesting studies on masculinity have recently appeared. Do we have the means to include as much on masculinity as on femininity? Can we seriously call our courses ‘gendered’ if we do not? 3. The practicalities of teaching. What works? What doesn’t? Two recent articles suggest possible solutions. a. Patricia Lorcin (in ‘Teaching Women and Gender in France d’OutreMer: Problems and Strategies,’ French Historical Studies 27.2; 2004) grapples with very similar issues (students who don’t read French, and need to be familiarized with the main outlines of French history) suggests two possible solutions: to introduce as many primary sources in translation as possible (novels, documents, film, images), and to combine a chronological approach with a thematic approach. b. Marilyn Booth (in ‘New Directions in Middle East Women's and Gender History’ Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History, 4.1; 2003) proposes the use of the concept of ‘space’. The idea of space has of course its own complex theoretical foundations, but thinking about space and its gendered construction can perhaps bring out fruitful contrasts and links between segregation and integration, public and private, inner and outer. c. Would any of these solutions work in the field of Chinese studies? Denise Gimpel introduced the teaching environment in which she works. She teaches students who take Chinese as their main field. Denise’s approach is to avoid theoretical materials related to gender in the first year. She prefers to introduce the students to primary sources, for example the Xiaojing written for men next to the Xiaojing for women, letting the students ask their own questions. In her experience, the students often raise concerns that lie at the heart of gender-related problematiques. Once students have raised the issues themselves, it is easier to come back to them with a more theoretical focus in more advanced-level courses. Denise highlighted three main characteristics in her teaching: 1. to use as many primary materials as possible. 2. to use comparative materials, placing for example the discussion of footbinding in the context of descriptions of the corset, or restrictions on women venturing outdoors with the first introduction of a public toilet for women in England in the early 20th century. Students are encouraged to reflect on their own norms and their own cultural assumptions. 3. to use as much material on men as possible. She encourages the students to see that men are not the ‘unproblematic norm’ they are often deemed to be. Birgit Haese teaches at the Centre for East Asian Studies in Dresden, where they offer an abbreviated form of area studies, often to students who study natural sciences as their main field. This means she teaches very heterogeneous student groups, and students who have little experience of texts and writing. Her focus is on images of women, and she begins by introducing the students to some theoretical and historical materials related to the feminist movement. Her classes focus on role models for women, women in the revolution, the marriage laws, the Cultural revolution rhetoric on gender equality and the one-child policy of the 70s and 80s. Naomi Standen teaches large classes of about 90 students in a course entitled ‘Imperial China’. Her approach is largely integrationist. She encourages students to reflect on their own experiences and positions in society, for example by making the students aware of their own social positions in relation to the court women of the Han dynasty. Marina Thorborg reflected on her experience of teaching Asian feminism since 1972. In recent years she teaches a strikingly large contingent of students from the Philippines. Mong her students gender is associated with the West, and hence with what is ‘modern’. Giovanni Vitiello remarked that the comparison to Classical Rome is often helpful for students. He teaches a module on gender, fiction and sexuality, relying on the fine translations of late imperial fiction by Hanan and Roy now available. Grace Fong remarked that the anthology by Kang-yi Sun Chang and Haun Saussy, and the forthcoming collection by Wilt Idema entitled Red Brush (Harvard University Press) make the introduction of primary sources much easier. Laurel Bossen remarked that mainstream anthropology textbooks now all integrate gender. Anthropology without gender has become inconceivable. Giovanni Vitiello pointed out the recent appearance of Song Geng’s The Fragile Scholar: Power and Masculinity in Chinese Culture (2004), which complicates the wen model of masculinity further. Glen Dudbridge remarked that perhaps our focus should be on the larger context. He encouraged us to question the hegemonic discourse, the ‘big views’. Resisting divisions of yin and yang or wen and wu, we should perhaps instead focus on ‘nonimperial’ China. Dagmar Shaefer added that in a newly established MA program in Wuerzburg, the students had very clear demands of acquiring a certain amount of knowledge, which she feels complicates the amount of gender that can be introduced to the students. Francesca Dal Lago highlighted the importance of introducing visual materials to the students. Maria Jaschok asked if we could really consider studying China without gender. She remarked that the ambiguities and complexities of gender are part of everything. In conclusion three observations: 1. The availability of primary sources in translation and online translations, collections of images, and documents make the use of primary sources in teaching entirely possible, and we should make use of these sources. It would be helpful to have lists of such online collections of primary materials useful for teaching gender on the WAGNet website, so please send in your suggestions to the listserv, and they will be posted. 2. We all work in very different institutional environments, and our students have different expectations of us. Do we teach them to read and write critically, or do we attempt to convey a certain amount of factual knowledge to them. We probably all make our own compromises, trying to find the right balance. 3. Institutions are more and more moving towards protecting the teaching materials we create by restricting access to them. It would be helpful to have examples of syllabi on the WAGNet website, so if you feel you would like to share your materials, please do so! Anne Gerritsen, Warwick University, September 10, 2004.