Andrew Carnegie and His Libraries

advertisement

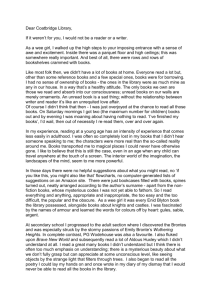

Foster 1 Sharon M. Foster Professors Bielefield and De Abreu ILS 503-Biography (amended) 17 April 2006 Andrew Carnegie and His Libraries Andrew Carnegie did not invent the modern American public library, but he probably did more than any other person to ensure its establishment as the institution that we know today. From 1881 to 1917, Andrew Carnegie and the Carnegie Corporation built public libraries in over one thousand communities in the United States and its territories, accounting for nearly 35% of the increase in the number of public libraries across America during that period. This growth accelerated trends that were already in motion, such as the opening of the stacks to the public and dedicating a space for children. Because of Carnegie, librarians became the victors in their longrunning disagreement with architects over how a library should be arranged. Most important of all, Carnegie’s gifts firmly established in the American psyche the notion of the public library as a resource for a lifetime of learning and an institution worthy of taxpayer support. Andrew Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland on November 25, 1835. His father, William, was a third-generation handloom weaver. (Krass 2) Though working class, he was prosperous compared to the tenant farmers, coal miners, and factory workers who barely earned a subsistence wage. (Krass 3) He was also a voracious reader who was cofounder of a small “social” library for weaver families. (Krass 11) Foster 2 Carnegie’s mother, Margaret, was the daughter of Thomas Morrison, a cobbler and a political activist who spoke publicly for land reform and against inherited privilege in all its forms. (Krass 3-5) As wages in weaving and other skilled professions came under increasing pressure from the Industrial Revolution and its impact on the laws of supply and demand, workers’ unions that advocated for voter and parliamentary reforms grew in numbers and influence. Members of Carnegie’s family, most notably his father and his mother’s brother Thomas, were active in this movement, whose supporters were known as Chartists, for their support of The People’s Charter, the manifesto of the London Working Men’s Association. (Krass 9-10) The Chartists would later splinter between those who advocated non-violent persuasion, such as Carnegie’s uncle Thomas, and those who argued for the use of physical force. (Krass 10) Many years later, Carnegie would find himself facing this same choice in dealing with the strikes at his steel mills. The Carnegie family emigrated to America in 1848, when Andrew was twelve years old. They settled in Allegheny, Pennsylvania, now a suburb of Pittsburgh, where Margaret’s sisters and their husbands had already settled. Andrew’s first job was as a $1.20 per week “bobbin boy” in the same cotton factory where his father worked, the family having found that making a living at handloom weaving was no more viable here than it was in Scotland. He quickly moved on to other work, eventually becoming a telegraph delivery boy. Andrew had had only four years of formal education in Scotland, which ended when the family moved to America. Thanks to the generosity of a local resident named Colonel James Anderson, who each Saturday made his personal library of 400 volumes Foster 3 available to all “working boys,” Carnegie was able to continue a self-directed education. Many years later Carnegie would write of Colonel Anderson, “to him I owe a taste for literature which I would not exchange for all the millions ever amassed by man. Life would be quite intolerable without it.” (Carnegie, Autobiography 44-5) In his early twenties, Carnegie was employed as a personal telegraph operator and secretary to Thomas A. Scott, the superintendent of the western division of the Pennsylvania Railroad. From Scott, he not only learned how to run a business, and in particular a railroad, but he also learned about investing. Carnegie’s father had passed away by this time, and his younger brother Tom was still in his teens. Carnegie’s mother mortgaged their house to obtain five hundred dollars, which Carnegie gave to Scott, who used it to purchase stock for Carnegie in the Adams Express Company. Adams Express paid a monthly dividend, and some time later a check for ten dollars arrived on Carnegie’s desk. It was then that he had his epiphany, writes Carnegie. “It gave me the first penny of revenue from capital—something that I had not worked for with the sweat of my brow.” It was like finding “the goose that lays the golden eggs.” (Carnegie, Autobiography 76) Over the next few years, Carnegie invested in many other businesses related to the railroad industry. In 1872 he had enough capital to build his own steel mill south of Pittsburgh, the largest steel mill in the United States that used the newly developed Bessemer process. (Hoogenboom) He continued to invest in new equipment and new processes that would lower his production costs, and expanded his business by buying suppliers such as coal and iron ore mines, and developing his own sales force. (Carey 5) He kept labor costs down as well, and the company was frequently plagued by labor Foster 4 strikes. In 1892 at the Homestead plant, a strike turned deadly when twenty men were killed in a clash between the striking workers and the Pinkerton detectives whom Carnegie had hired as “guards” and “watchmen.” (Krass 284) Considering his family origins, the irony of finding himself on the other side of the struggle between management and labor was surely not lost on Carnegie. Four years later, in 1896, Carnegie visited Homestead and announced his intention to donate $400,000 to build a library and other community facilities. (Krass 327) In an 1889 essay titled “Wealth,” Carnegie explained his "gospel of wealth," which was that those who accumulated such "surplus wealth" as he had done, merely held it in trust for the public good. (Carnegie, Wealth 19) He made no attempt to justify the extreme divisions of rich and poor that capitalism produces, except to say that to change this state of affairs would require a radical change in human nature. He then went on to examine three different ways by which a wealthy man may dispose of his riches. First, he could hold onto it until his death, leaving it all to his heirs. Carnegie considered this the least desirable result, having seen the unhealthy effects of inherited wealth on the sons of his peers. Second, he could direct that it be given to various charitable and philanthropic efforts after his death, but Carnegie found this unsatisfactory, mainly because the money would have to be entrusted to someone else to carry out the desires of the deceased. The third way, giving the money away while he was still alive to control where it went and to what uses it was put, seemed to him the superior method. In his opinion, the man who had created the wealth was also the best able to decide where it would do the greatest good for the greatest number of people. (Carnegie, Wealth 26) Foster 5 In 1901, the Carnegie Steel Company was sold to the company that later became United States Steel Corporation. Carnegie’s share of the sale was over $225 million in interest-bearing bonds. (Hoogenboom) Over the next eighteen years, until his death in 1919, he gave away that much and more to libraries and other institutions in the U.S., the U.K., and Canada, in order to provide "ladders" that others might climb the way he did. Based on his experience as a young man who educated himself in Colonel Anderson’s library, Carnegie determined that endowing libraries would be the best use of his “surplus” wealth. They would be free to all but, because effort on the part of the recipient was required in order to obtain any benefit, it was in no way demeaning, as a handout would be. As he wrote in his essay, “The Gospel of Wealth,” “In bestowing charity, the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves; to provide part of the means by which those who desire to improve may do so; to give those who desire to rise the aids by which they may rise; to assist, but rarely or never to do all. Neither the individual nor the race is improved by almsgiving.” (Carnegie Wealth 27) Whether it was out of guilt or a genuine belief that, in his words, "the man who dies thus rich dies disgraced," Carnegie did a wonderful thing. It could be argued, and it was argued by his critics, that the wealth spent on these philanthropies was actually created by the workers, skilled and unskilled, who worked in the mills, and that the money should be returned directly to them. (Wall 811) Biographer Peter Krass, whose own great-grandfather worked in a Carnegie mill, began the research for his book with equal parts of respect and disdain for the man, as he writes in his preface. But the more he learned about the man, and the more time he spent in Carnegie-funded parks and museums, the more he began to appreciate Carnegie’s achievements. “Both purposefully and unwittingly he planted seeds for civilization,” Krass writes. “While Foster 6 trampling asunder thousands of workingmen, he ultimately uplifted millions of people in the future.” The number of libraries that were built with Carnegie money varies depending on whether the survey counted the number of communities that were served, the number of grants that were awarded, or the number of actual buildings that were built. In some instances, one grant might cover one community, but more than one building—a main library and one or more branches, for example. (Bobinski 15) In other instances, one community might receive more than one grant—an initial one for the building, and then an additional grant to cover other expenses. Eight grants were awarded to communities in Oklahoma before it became a state in 1907. One survey of public library growth from 1896 to 1923, published in 1924 by a member of the Carnegie Foundation For the Advancement of Teaching, counted 1,408 communities that owned a Carnegie library building. (Learned, Appendix) A 1932 biography, referring to a 1919 survey, identified 1,946 Carnegie libraries built in the United States. (Hendrick 207) A detailed history of the Carnegie libraries published in 1969 counted 1,679 buildings in 1,412 communities. (Bobinski 16) Whatever the actual number, it was a significant percentage of the approximately 3,900 American communities possessing public libraries by 1923. (Learned, Appendix) It is also very likely that the sudden growth in library buildings financed by Carnegie and, later, the Carnegie Corporation, also spurred other communities and their local philanthropists to construct new libraries. (Lee 36) There were only a few conditions for obtaining a Carnegie grant for a new library building. The community was required to have a site for the library and be willing to commit to an annual budget appropriation for books, staff, and heating that was Foster 7 equivalent to ten-percent of the cost of the building. (Krass 327) The size of the library, and therefore the amount of the grant, was determined by the size of the community. Little or no allowance was made for future growth, or for the possibility that the resulting structure might attract patrons from a much larger region. The grant was only to be used for the construction of the building itself. The community was responsible for everything else, thus firmly establishing the public library an institution as worthy and necessary as public schools. Biographer Hendrick quotes Carnegie as having once said, “I do not wish to be remembered for what I have given, but for that which I have persuaded others to give.” (Hendrick 203) James Bertram, Carnegie’s personal secretary, was responsible for managing the approval process and verifying that the community followed through on its obligations. Carnegie did not select the architect or mandate a particular floor plan, but he did have final approval of the building plans and hated to see his money used for features that he considered wasteful, such as domes and “too many” columns at the entrance. He favored a one-story floor plan, with a basement for the heating plant and other necessities. He also favored book stacks that were open to public browsing, so what was formerly the “delivery desk,” where patrons submitted their literature requests and waited for a page to fetch it from the closed stacks, now became the “circulation” desk, where patrons brought their selections to be checked out. In 1911, Bertram produced a brochure titled “Notes on the Erection of Library Bildings,” which he sent to every community that was approved for a grant. (Carnegie and Bertram, like their contemporary Melvil Dewey, were advocates for spelling reform.) Among other details, the brochure contained examples of acceptable floor plans. (Bobinski 58) Foster 8 Carnegie never required that any library be named after him, although several were. He preferred that they simply be named “Free Public Library,” prefaced by the name of the community. Although acceptable plans included a Lecture Room, Carnegie insisted that the building be used exclusively for library purposes. Most of the Carnegie libraries were built in the Central and Western regions, Indiana topping the list with 164 buildings. (Bobinski 20) But even New England, which already had a tradition of public support for libraries (the Boston Public Library having been established in 1854), received a total of 84 Carnegie libraries. (Learned, Appendix) Only Rhode Island was left out. Connecticut, which by 1896 already had 61 communities that possessed a public library with at least a thousand volumes, received a total of eleven libraries: Bridgeport (two branches), Derby Neck, Enfield, New Haven (three branches), Norwalk, South Norwalk, Unionville, and West Haven. Several of these are still functioning as libraries, and others have been converted to other community uses. (Jones 135) The South Norwalk Branch Library web site informs visitors that the library is undergoing renovations that Mr. Carnegie did not foresee, such as wheelchair accessibility, spaces for public computers, and population growth Andrew Carnegie believed that human beings could be improved, perhaps even perfected, by the rooting out and elimination of ignorance. The best means of doing that, he believed, was the free public library. He could not have foreseen the overwhelming allure of the passive information-gathering activity of watching television, but if he had, he probably would have been appalled at the wasted human potential. At one time the world’s richest man, he decided that the rich merely held their surplus Foster 9 wealth “in trust,” to be used for the benefit and improvement of all of mankind. Undoubtedly, the excesses of today’s corporate executives would have appalled him. I like to think that Carnegie had the right idea, but perhaps an overly optimistic view of the timeframe required to root out and eliminate ignorance. Today we have the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which in a very real sense picked up where Carnegie left off, making grants and gifts of computers and software to under-served communities across America. The modern public library which Carnegie, more than any other single person, firmly planted in the culture of 20th century American life, will survive and thrive in the 21st century. Foster 10 Appendix Here is a very small sample of the libraries that Carnegie money built. Many more photographs can be found at the Aulik web site, and in the books by Jones and Van Slyck. Cleburn, TX 1903 $20,000 Tyler, TX 1903 $15,000 Jefferson, TX 1906 $10,000 Derby Neck, CT 1906 $3,400 West Haven, CT 1913 San Antonio, TX 1900 $70,000 Foster 11 Works Cited Aulik, Judy. Library Postcards: Civic Pride in a Lost America. <http://home.comcast.net/~jaulik/index.html> 10 April 2006. Bobinski, George S. Carnegie Libraries: Their History and Impact on American Public Library Development. Chicago: American Library Association, 1969. Carey, Charles W., Jr. “Carnegie, Andrew.” American Inventors, Entrepreneurs, and Business Visionaries, American Biographies. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2002. Facts On File,Inc. American History Online. <http://www.fofweb.com> 8 February 2006. Carnegie, Andrew. Autobiography of Andrew Carnegie. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948. Carnegie, Andrew. The Gospel of Wealth and Other Timely Essays. Edward C. Kirkland, ed. Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1962. Hendrick, Burton J., The Life of Andrew Carnegie: Volume 2. New York: Harper & Row, 1932. Hoogenboom, Ari. “Carnegie, Andrew.” In Hoogenboon, Ari, and Gary B. Nash, eds. Encyclopedia of American History: The Development of the Industrial United States, 1870 to 1899, vol. 6. New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2003. Facts On File, Inc. American History Online. <http://www.fofweb.com> 8 February 2006. Jones, Theodore. Carnegie Libraries Across America: A Public Legacy. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1997. Krass, Peter. Carnegie. Hoboken: John Wiley, 2002. Foster 12 Learned, William S. The American Public Library and the Diffusion of Knowledge. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1924. Lee, Robert Ellis. Continuing Education for Adults through the American Public Library 1833-1964. Chicago: American Library Association, 1966. South Norwalk Public Library, <http://www.norwalklib.org/nplsono/index.htm>, 2 April 2006. Van Slyck, Abigail A. Free To All: Carnegie Libraries & American Culture 1890—1920. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995. Wall, Joseph Frazier. Andrew Carnegie. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970.