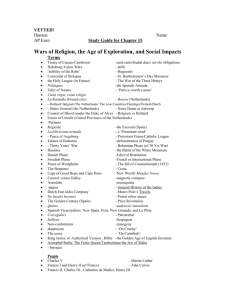

WARS OF RELIGION AND THE CLASH OF WORLDVIEWS – CH

advertisement

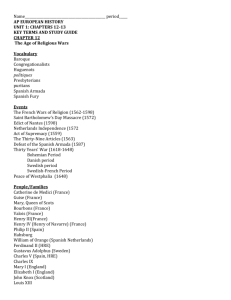

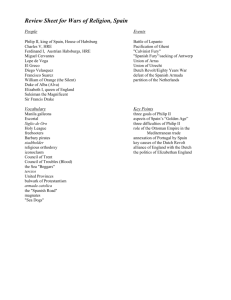

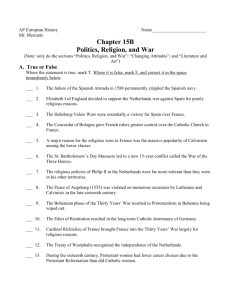

WARS OF RELIGION AND THE CLASH OF WORLDVIEWS – CH. 14 (Pt. 2) OVERARCHING QUESTION FOR CH.14 (Pt. 2) What were the long-term political, economic, and intellectual consequences of the conflicts over religious benefits? THE THIRTY YEARS’ WAR The THIRTY YEARS’ WAR devastated central Europe and permanently altered European politics. It contributed to the shift in power from southern and eastern Europe toward the northwest. It was the bloodiest and last of the wars of religion in Europe. Its resolution by the PEACE OF WESTPHALIA inaugurated a new diplomatic pattern, whereby wars were settled through meetings involving the combatants. This practice is still common today. The war’s outcome also further altered the political balance of power. The Holy Roman Empire declined relative to France, which surpassed Spain to become the strongest state in continental Europe. Sweden emerged as the dominant state in Northern Europe and England benefitted from staying out of the war, avoiding further expenses and destruction. NEW DEVELOPMENTS The crisis precipitated by the wars of religion, the climatic change produced by the Little Ice Age, and the economic recession of the early seventeenth century prompted some Europeans to seek new, non-religious sources of authority. New ideas were developed in the arts, politics and philosophy, which led to the creation of a secular worldview based on scientific research and reasoning. For example, HENRY IV brought the French wars of religion to an end by placing the order and security of the state above matters of faith. His actions were justified by the writings of Jean Bodin, who advocated strong monarchical power as the best means of maintaining order. In the arts, theatre began to flourish, as exemplified by the works of William Shakespeare, which reflected timely concerns over the nature of power and the crisis of authority. Mannerism and the baroque, as well as the opera, possessed a new theatrical style that emphasized emotion. In the natural sciences, empiricism, heliocentrism and the grand synthesis of Isaac Newton’s laws of movement offered a new, rational vision of the universe that did not depend on God. EUROPEAN CULTURE AND SOCIETY Despite breakthroughs in secular thinking, European culture and society remained complex and sometimes contradictory. Leading scientists also practiced alchemy and astrology. Meanwhile, a witch craze swept across Europe, targeting the most vulnerable and marginal women in society. Inequality, oppression and persecution persisted and even expanded in certain areas. Religious authorities, notably the Catholic church opposed the new scientific thinking and brought men such as GALILEO GALILEI before the INQUISITION. Slavery expanded in the colonies of the New World and serfdom intensified in eastern Europe, most notably in Muscovy. This accelerated the divergence in the experiences of eastern and western Europeans, a pattern that would last through the twentieth century. MAIN CHAPTER TOPICS 1. The PEACE OF AUGSBURG (1555) officially recognized LUTHERANISM within the Holy Roman Empire. However, they did not recognize CALVINISM. Nevertheless, Calvinism expanded rapidly after 1560, altering the religious balance of power in Europe and producing political repercussions – including civil war and revolt – in the Netherlands, France, Scotland and other parts of Europe. 2. PHILLIP II of Spain, the most powerful monarch of his time, did not succeed in his quest to restore Catholic unity in Europe, nor did he succeed in his efforts to destroy political enemies in France, the Netherlands and England. England and the Netherlands emerged from the conflict as great European powers in economic and military terms. 3. The THIRTY YEARS’ WAR was the last and most deadly of the wars of religion. It began in 1618 and ended in 1648. By its end, much of central Europe lay in ruins and the balance of power had shifted away from the HASBURGS – the monarchs of Spain and Austria – toward France, England and the Dutch Republic. The war’s large armies necessitated bureaucracy and powerful centralized states. 4. The Thirty Years’ War exacerbated the economic crisis that was already under way in Europe. Famine and disease further contributed to the suffering. The war shifted the economic balance of power; as the war ended, northwestern Europe began to dominate international trade, but the Spanish and Portuguese retained pre-eminence in the New World. 5. Even as religious wars raged on, thinkers created nonreligious theories of political authority and scientific explanations for natural phenomena. In this revolution, the Dutch Republic, England, and to a lesser degree, France, led the way, Nevertheless, many still believed in magic and witchcraft and accepted supernatural explanations for natural phenomena. 6. The SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION overturned the theories of Ptolemy and Aristotle, which had passed unquestioned for centuries. However, more important was the early-seventeenth-century insistence on deductive and inductive scientific investigation that created the basis for rapid expansion of knowledge. CHAPTER REVIEW QUESTIONS (& ideal answers) 1. How did state power depend on religious unity at the end of the sixteenth century and the start of the seventeenth? Religion had been deeply entwined with political rule for centuries. A ruler’s contract with citizens included his responsibility to uphold the “true religion”. Religious beliefs fostered powerful loyalties, so religious division easily became political conflict. However, the conflicts that emerged threatened to undermine the strength of the European nations. France and the Netherlands ultimately placed state strength over religious conformity by the end of the sixteenth century by instituting religious toleration. In Spain and England, religion remained a national force, determined by the preference of the crown, in Spain for Catholicism, in England for Anglican Protestantism and as such, religious unity contributed to the strength of state power. Religious disunity in Spain’s empire however, undermined Spain’s ability to retain control for the Netherlands. In the Ottoman realm and eastern Europe, religious toleration strengthened states by ensuring peace; religious conflict was disruptive to social order and state building. When the monarchs, church and citizenry were in agreement, religious unity could contribute to state power, however it was no longer essential. 2. Why did the war fought over religious differences result in stronger states? The Thirty Years’ War made it clear that state interests had become far more important than religious concerns, as the governments worked to maintain armies and retain territory. The costs and logistics of war required new systems for taxes and bureaucracies of management. Developing these increased the centralization and strength of state authority. 3. What were some of the consequences of economic recession in the early 1600s? Economic decline was compounded by years of poor harvests, which were followed by famine and disease. Such conditions contributed to large-scale uprisings and revolts in some places.\In other places, many responded to famine by migrating in search of better opportunity, which created a significant homeless population. The crisis widened the gap between rich and poor and constrained women’s opportunities. In the long term, patterns of family changed, as marriages were postponed until people got older, resulting in families with fewer children. The shifting economic balance among states triggered by the recession favoured northwestern European countries that were well positioned for the growing Atlantic trade. England, the Dutch Republic and France began to assume dominance in commerce. 4. How did belief in witchcraft and the rising prestige of scientific method coexist? Magic and science had long been associated as two forms of intellectual pursuit. Even as scientific understanding grew, many still believed in alchemy, astrology and other elements of what we called “natural magic”. Witchcraft fell within this line of thought as a “black magic”. Science was still a long way from explaining everything and especially in times of social s tress, the search to explain a crisis readily turned to blaming unknown forces. 5. How did the balance of power shift in Europe between 1550 and 1648? What were the main reasons for the shift? Economic power shifted from Spain, Portugal and the Mediterranean world to the nations of northwestern Europe, as commerce with the Americas became a significant force in European state building. Initially strengthened by the precious metals mined in Latin America, Spain lost power when those resources declined. England, France and the Netherlands positioned in ideal geographic locations for developing trade across the Atlantic, which strengthened their economic power. England was especially well positioned, having been sheltered from the ravages of the Thirty Years’ War. 6. Relate the new developments in the arts and sciences to the political and economic changes of this period of crisis. The decline in the attachment of religious authority to public policy fostered growing interest in searching out nonreligious explanations for political authority and natural phenomena. Thinkers who felt less constrained by the potential censorship or persecution of the church were more willing to look beyond the previously accepted explanations. Instead, they sought explanations that were based in the verifiable evidence of the natural world. Secular subjects and secular values became more common themes in the arts. Theatre explored topics of current concern related to the politics and social issues. The dramatic religious emotionality of mannerism and baroque art reflected reformation Catholicism.