Sociolinguistic variation of the prosody of particle hoonn in Southern

advertisement

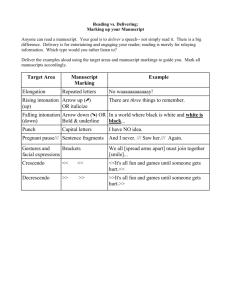

Sociolinguistic variation of the prosody of particle hoonn in Southern Min Yiching Huang Abstract This paper investigates the pragmatics and intonation of particle hoonn in Southern Min and the adults’ preference in the use of pragmatic functions when the child was 2, 4 and 5 years old. By considering the intonation of pragmatic functions, we found that the intonation would vary because of Li’s (1999) six different pragmatic functions: requests for confirmation, informing-reception sequence, backchanneling, reportings, expressive utterances and direct utterances. To understand whether the pragmatic functions can account for the intonation variation of hoonn, this study examined the pitch contours for particle hoonn in discourse. The statistical results of this study show that the three functions ‘requests for confirmation, backchanneling and expressive utterance’ favored rising intonation while informing-reception sequence, reportings and direct utterances favored falling intonation. To investigate whether there is a preference in the use of functions, the study compared the frequencies of these six pragmatic functions at the 3 age levels (2, 4 and 5). The results show that there is a preference in the adult’s use of functions addressing the child at 3 age levels. The function of ‘direction’ was used more frequently when the child was 2 years old and least frequently when the child was five years old. The findings of this study have clarified the relationship between the pragmatics and prosody of the particle hoonn in discourse. Furthermore, a new approach to investigating the pragmatics of particle and their interaction in Southern Min is proposed. Key words: Taiwanese particle, Prosody, Pragmatics, Age 閩南語助詞 hoonnup 音調的社會變異 黃意晴 摘要 本篇文章旨在探討閩南語中的語助詞 hoonn 的語用功能與音調的使用情形 及對 2 歲和 5 歲的小孩說話時,是否有偏好某些特別的語用功能。藉由檢視這些 語用功能的音調,我們發現音調會隨著不同的語用功能而改變。根據李櫻(1999) 對語助詞 hoonn 的分類,總共有六種語用功能,分別是要求確認、告知-接受的 語句組、回應、報導、表達情感的語句及指引的語句。 為了瞭解語用功能是否可以影響語助詞 hoonn 的音調改變,本文檢視了語助 詞 hoonn 在語境中的音調變化。而統計結果發現以下三種功能「要求確認」 、 「回 應」及「表達情感的語句」傾向較常使用上揚的音調;而另外三種功能「告知接受的語句組」、「報導」及「指引的語句」較傾向於使用下降的音調。 本文也探討了對不同年紀的兒童說話是否有在語用功能上有特別的偏好。根 據統計結果顯示在這三個齡層分別是 2 歲、4 歲和 5 歲時,大人在語用功能上的 確有特別的偏好。當兒童兩歲時,大人使用「指引的語句組」的頻率最高,接著 當兒童逐漸長大至五歲時,大人使用「指引的語句組」的頻率最低。 最後,根據以上的研究結果發現了語助詞 hoonn 在語用及韻律之間的關係, 也進一步提出了運用統計方式來探討語助詞的語用功能在閩南語裡與音調之間 的互動關係之新的研究法。 關鍵詞: 閩南語助詞、音調、語用、年紀 1. Introduction Discourse analysis of Chinese particles has been well-researched (e.g., Yang 1995; Hsieh 2000; Lee 2000). The studies of particles and interjections in Mandarin Chinese reveal that the functions of these particles and interjections could be influenced by internal or linguistic factors..However, very little research has focused on the relationship between prosody and pragmatics in Southern Min in terms of a sociolinguistic perspective, i.e., to investigate what factors account for the variation in intonation. Li’s (1998) found that the particle hoonn may permit a range of interpretations in different contexts from 16-hour recording of natural spoken data and its core pragmatic function remains invariably as a negotiation marker. That is, hoonn is a discourse marker which signals the speaker’s communication intention for potentially necessary negotiation, which in turn is motivated by the dynamic nature of interactional communication. However, Li’s study did not address the relationship between pragmatics and intonation. So far, the prosodic study that I know of has mainly concerned about the contextual meaning of interjections with prosodic forms (Yang, 2010). Specifically, little is known about whether the intonation variation is related to the different discourse functions, although this relationship has been found in other languages. According to Escudero-Mancebo & Cardeñoso (2006) , sometimes the intonation could provide linguistic information to distinguish the sentence-type or emotional information used to express the speaker’s emotion. Gumperz (1982) also pointed out that intonation can serve as a contextualization cue which carries information, the meanings of which is conveyed as part of the interactive process. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether there is a similar situation in Southern Min, i.e., whether the pragmatic functions of particles would have an effect on prosodic forms or intonation in Southern Min. The study also aims to examine the child’s acquisition of communicative competence from the interaction with the adult. Based on Lantolf’s (2000) sociocultural theory of language learning, child’s development depends on the interaction with a more knowledgeable person. 2.Methods 2.1 Research Questions The study examined two questions, the first of which is to see whether pragmatic functions will account for the intonation variation of the Southern Min particle hoonn. There is a specific intonation of some pragmatic function, for example, when one asks a yes-no question in English, one usually raises the intonation of the whole sentence. Example (1) illustrates a Chinese yes-no question with a rising intonation: (1) Mary 是 學 生 Mary shì xué shēng 嗎﹖ ma? “Is Mary a student?” The second one is to observe whether there is a preference by the adult in the use of pragmatic functions to address a child of 3 age levels (2, 4 and 5 years old) Although there are six pragmatic functions, not every functions is used equally. There must be some preference in the use of functions according to the child’s age. 2.2 Hypotheses The use of rising or falling contours has been used to distinguish sentence types such as statement, questions, or commands in traditional grammatical account of the function of intonation. As Escudero-Mancebo & Cardeñoso (2006) point out that intonation is related to various information, one of the information is linguistic information which can distinguish interrogative or declarative sentences. Therefore, based on this statement, the hypothesis for the first research question is as follows: The intonation could be used to distinguish functions such as question or statement; therefore, the functions can account for the intonation variation. Previous studies (e.g., Church, 2000; Wittner & Petersen, 2006) show that communication with different strategies can teach the child how to talk and learn the pragmatics of conversation; therefore, based on these findings, the hypothesis for the second research question is as follows: The adults will adjust their use of pragmatic functions according to the child’s age; therefore, there is a difference in the adult’s use of functions to address the child at different ages. 2.3 Source of Data There are totally 501 tokens in this study. The data analyzed came from the Taiwanese Child Language Corpus (TAICORP) (Tsay 2007), which is a corpus of spontaneous speech between young children and their adult caretakers in Southern Min speaking families. The child who contributed to the corpus was recruited from a Southern Min-speaking family in Min-hsiung Village, Chiayi County. The age range is between 2;7 and 5;3. The adult caretakers who participated were the children’s mother, grandmother and the two investigators of the corpus, respectively. In the case of this study, the data of a little girl, LMC in this corpus was analyzed with a focus on the conversation with her mother and the two investigators. 2.4 Data collection The tools we used here are a set of professional headphones, professional microphone and a portable mini-CD recorder to conduct the regular home visit for children. The data were collected by Rose Huang and Joyce Liu and transcribed also by Rose Huang and Joyce Liu. The pitch of the particle hoonn was measured by the author, using Praat (Boersma & Weenink, 2009), which is a free scientific software program for the analysis of speech in phonetics. 2.5 Procedure Firstly, the six pragmatic functions of hoonn were classifed according to Li’s (1999) study: requests for confirmation, informing-reception sequence, backchanneling, reportings, expressive utterances and direct utterances. The definitions of the six pragmatic functions are presented with illustrations, as shown below: (1) Requests for confirmation: To request for the addressee’s confirmation. e.g A: 台 灣 之 聲, Tai wan ci siann “The voice of Taiwan (the name of a radio show).” B: 喂, 陳 先 生 hoonn? Ue tan siannsin hoonn “Hello, is Mr. Chen?” A: 是。 Si “Yes.” (2) Informing-reception sequence: To suffix the utterance which indicates receipt of information. e.g A: 我 遮 e0 票 Gua ciah 攏 你 e phio long li 的. e “We all will vote for you.” B: 按呢 hoonn? Anne hoonn “I got it.” (3) Backchanneling: Often occurs as a free-standing particle without being tagged to any utterance. e.g A: 伊 I 咧 教 體育。 leh ka theiok “He teaches physical education.” B: Hoonn。 Hoonn “Mm.” A: 佇 台北。 Ti taipak “In Taipei.” B: Hoonn。 Hoonn “Mm.” (4) Reportings: When a speaker is telling a story, stating his opinion, or presenting a report. e.g A: 我 是 希望 想 講 hoonn,這個 節目 真 好 la, Gua si hibang siunn kong hoonn, citle ciatbok cin “I just want to say, this channel is very good, ” A: 我 是 希望 你 小可 教 一寡 台灣人 Gua si ho 出國 la [m hibang li siokhua ka citkua taiwanlang chutkok “I hope you can talk about the manner when Taiwanese 旅遊] e [m 禮節] hoonn,…. liuyou e lijie hoonn,… go overseas [hoonn].” (5) Expressive utterances: Usually to express apology, appreciation, and blessing and so on, to make sure that the interlocutor feels the speaker’s sincerity. e.g A: 失禮 hoonn。 Sitle hoonn “Sorry [hoonn].” (6) Direct utterances: Often occurs in the guidance, suggestion and command sentences. e.g A: 莫 食 傷 濟 hoonn。 Mai ciah siunn cue hoonn “Don’t eat too much.” Then we examined each utterance which hoonn occurs in the conversation between the adult and the child, and according to the context of conversation, to distinguish what kind of pragmatic function the adult used. The next step is to use Praat to extract the pitch values of hoonn, and take three values (onset, midpoint and endpoint) to represent the intonation of hoonn. Based on Masataka’s (1992) measurement, the rising or falling pitch was determined.” A token pitch was judge as rising or falling depending on whether the value of a frequency-modulation range of a continuous slope exceeded 15 Hz in material vocalization. That is, if the difference between the endpoint and the onset is higher than 15, it is rising. Otherwise it is falling. The statistical procedure ‘VARBRUL’ was used to find the most parsimonious model to account for the intonation variation. Finally, the frequencies of each function were calculated to run a Chi-square test to see whether there is a relationship between the frequency of adult’s use of pragmatic functions and the child’s age. 3.Results and discussion This paper addresses whether pragmatic functions and adressee’s age will account for the pitch variation of the Southern Min particle hoonn, and whether there is a preference in the use of pragmatic functions among 3 age levels (2, 4 and 5 years old). According to Li’s (1999) definition, six pragmatic functions were coded, containing backchanneling, request for confirmation, reporting, expressive utterances, directive utterances and informing-receiving sequence. These functions are complementary and exhaustive. Each hoonn in one sentence has only one pragmatic function. For example, when the speaker gives suggestion that do not eat too much to the hearer, the words the speaker said is just a statement, it cannot be an interrogative function simultaneously. 3.1 VARBRUL results We used VARBRUL program, which examined whether the independent factor groups can account for the variation in the dependent variables, to analyze the intonation variation of hoonn. We found that the independent factor group ‘pragmatic functions’ accounted for the intonation variation of hoonn as shown in table 1. Table 1: Weight for the factor group ‘pragmatic function.’ Functions Rising Backchannel .587* Confirmation .695 Reporting .347 Expressive .737 Informing-receiving .402 Direct .397 Range .390 *Note: The probability weights above .50 indicate favoring the application rule of intonation. Among the six pragmatic functions of hoonn, backchanneling, confirmation and expressive functions favor rising intonation while reporting, informing-receiving sequences and direct utterance favor falling intonation. According to Chun’s (1988) study, intonation is a useful tool to negotiate meaning, manage interaction, and achieve discourse coherence. From table 1, we can see not every pragmatic function used the same intonation. There is still some variation in intonation. Therefore, we can infer that sometimes people use rising or falling intonation to indicate different functions. As Escudero-Mancebo & Cardeñoso (2006) point out that intonation is related to various information: linguistic information (interrogative vs. declarative sentences), emotional information (the mood of speaker), and sociolinguistic information (social and geographical origin of the speaker), we can understand these three functions: backchannel, requests for confirmation, and expressive utterance tend to have rising intonation of the whole sentence to show the linguistic information (a question or a statement) or express the speaker’s excited emotion (happy or angry). In Yang’s (2010) study, she pointed out there is relationship between prosodic forms and functions of interjections in Mandarin. As Mandarin and Taiwanese are both tone languages, I believe that there is also a relationship between pragmatic functions and forms of final-particles in Taiwanese. The particle - ‘hoonn’was selected because it occurs frequently in Taiwanese. From table 1, we know pragmatic functions are significant to account for intonation variation, so we can know intonation can be influenced by internal factor (linguistic). The three functions, i.e., backchanneling, requests for confirmation and expressive utterances, tend to use rising intonation more than the other three. Sometimes ‘backchannling’ uses rising intonation to display emotional stance, such as surprise or interest (Jan Svennevig, 2004). ‘Requests for confirmation’ tends to be expressed with the rising intonation to confirm what the child said because the adult is waiting for an answer. Sometimes adults also use rising intonation more to express their emotion, attempting to capture the child’s attention or get her approval. As for the other three functions (reporting, informing-receiving sequence and direct utterances), all of them favored falling intonation. When the adult uses the function of ‘informing-receiving sequence’ with a falling intonation, she/he wants to let the child know she received her information. When the speaker uses the function of ‘reporting and direct utterance’ with falling intonation, it means she is describing something or giving a suggestion. No response is expected from the child when the adult used these three functions with falling intonation. That’s why these three functions favor falling tone. We can infer that the intonation of particle hoonn is like a kind of contextualization cue (Gumperz 1982). Contextualization cues carry information, the meanings of which is conveyed as part of the interactive process .There is an example (a), the teacher is asking a question to the students: (a) Teacher: Can you guess what does this word mean? Student: I don’t know (with rising intonation). sTeacher: Then, who can guess the meaning of this work? The student uses rising intonation to give a cue which indicates further support or encouragement. But the teacher misinterprets the contextualization cue as unwilling to answer the question. In the following dialogue, the adult is drawing with the child: (b)Adult:這 1 [/] 這 1 你 家己 寫 e0 Ce ce li kati sia e “Did you write this by yourself?” Child:henn0 a02. Henn a ma0? ma ”Yes.” Adult:用 [m 蠟筆] 寫 e0 hoonn0? (with rising intonation.) Iong labi sia e hoonn “Did you write it by crayons [hoonn]?” Child: henn0, [m 藍色] e0 [m 蠟筆]. Henn lanse e labi “Yes, blue crayons.” Here she raised her intonation of particle to give a cue to the child to give her the confirmation. When you use the rising intonation, you are waiting for a feedback, like the example above; however, when you give a suggestion or response with falling intonation, you just give an instruction to the interlocutor without expecting a response or you want the interlocutor knows you received the information. Like the following example (c)(A stands for adult): (c)A:你 愛 2 共 Li ai ka hoonn0? hoonn 伊 i 講 彼1 kong hit 是 si 啥物, a01 siannmih, a 彼1 會1 hit e 按怎 a02, ancuan a “You need to tell him what that is and what could happen to it [a] [hoonn]?” The adult simpy told the child what to do and did not expect any response from her. In other words, she gave a statement with falling intonation. Since it is not a question, the child did not need to respond. Therefore, the intonation here is not only a linguistic information but also a contextualization cue. 3.2 Chi-square results Here we used chi-square to analyze the second research question: whether there is a preference in the adult’s use of pragmatic functions to address the child at 3 age levels (2, 4 and 5 years old). Here, we used a Chi-square test to examine the relationship between age and these six functions. The result shows the adult’s preference, as shown below in Table 2. Table 2: The standardized residual of six functions among 3 age levels. Backchannel Request Direct Expressive Inform Report 2 yrs old -.1 -1.3 2.2 -1.3 .5 -.4 4 yrs old -1.4 .5 1.2 1.4 -1.1 2.0 5 yrs old 1.4 .7 -2.9 -.2 .6 -1.5 When a standardized residual for a category is greater than 2.00 (in the absolute value), we can conclude that it is a major contributor to the significant X2 value (Hinkle, Dennis E., Wiersma, William, Jurs, Stephen G, 1988). From table 2, we can see the residual of directive utterance was used more frequently by the adult when the child was 2 years old because the adult needs to teach the child to learn to follow the directions to accomplish individual tasks. This result supports Poole, Miller, and Church’s (2000) finding that the young children enjoy following simple requests and can feel good about cooperating from adults’ support. When the child was 5 years old, directive utterance was used least. Based on Committee on psychosocial aspects of child and family health’s (1998) study, “As children grow older and interact with wider, more complex physical and social environments, the adults who care for them must develop increasingly creative strategies to protect them and teach them orderly and desirable patterns of behavior. Preschoolers begin to develop an understanding of rules, and their behavior is guided by these rules.” When the child gets older, s/he will bear these rules in mind, so the adults will change the strategies and do not need to use direction directly to the preschooler. Based on Thompson’s (2006) and Wittner and Petersen’s (2006) thesis, Children can acquire discourse competence and strategic competence through the interaction with the adult and also help them become a conversational partner and a capable communicator as Hymes (1972) pointed out ‘when to speak, when not, what to talk about with whom, when, where, and in what manner to interact.’ 3.3 Summary When we speak, we attempt to convey the listener some quite complex information about how we intend them to deal with the message. The common way we use in the spoken discourse is to vary our intonation of sentence, e.g., we use rising intonation to indicate a question or falling intonation to mean a statement. The intonation could be a ‘contextualization cues’ (Gumperz,1982). The results of this study indicate three of the six pragmatic functions, i.e., ‘backchannelling, request for confirmation and expressive utterance’ tend to use rising intonation more than the other three. In Gmperz’s (1982) chapter on ’Prosody in the conversation’, he shows ‘how conversationalists use prosody to initiate and sustain verbal encounters’. When the adult gives the rising intonation, it means that she initiates the interaction with the child and hopes the child to give her a response. Children can acquire discourse competence and strategic competence through the interaction with the adult, that is, knowing’ when to speak, when not, what to talk about with whom, when, where, and in what manner to interact’ (Hymes, 1972). From the statistical results, the adult has different preference in the use of pragmatic functions to address the child at different age levels. It indicates the adult provides a scaffolding like Lantolf’s (2000) sociocultural theory of language learning, which originally conceived of by Vygotsky. It is suggested that child language development depends on the interaction with people and culture to help the child acquire the language skills and listen to the intonation to deal with the message on ‘how to respond now’ from the interaction with the adult. 4. Conclusion In this study, we investigated the relationship between pragmatics and prosody of the particle hoonn in Southern Min, and also observed the adult’s preference in the use of pragmatic functions to talk with the child at different age levels. We found that the relationship between pragmatics and prosody is closely connected because the intonation plays an important role in the social contexts. The statistical results of this study show that the three functions ‘requests for confirmation, backchanneling and expressive utterance’ favor rising intonation while informing-reception sequence, reportings and direct utterances favor falling intonation. In light of what Gumperz (1982) proposed, that is the ’contextualization cue’, which can carry information as part of the interactive process. The adult uses different intonation to imply that she initiates the interaction with the child and expects the child to give her a response. The statistical results also show that there is a difference in the use of pragmatic functions to the child at different age levels. We found that the function ‘informing-receiving sequence’ was used more frequently when the child was 2 years old and the adult used these two functions ‘request for confirmation and informing-receiving sequence ’ more frequently when the child was older. When the child grows up and becomes talkative, the caretaker would also use questions often to stimulate the interaction. The adult’s change of pragmatic functions provides a scaffolding for the child to acquire discourse competence and strategic competence through the interaction with the adult. This paper may not be adequate in presenting the relationship between the pragmatics and prosody of the particle hoonn in Southern Min and the situation of the preference in the use of pragmatic functions between the adult-child’s interactions because the data is neither sufficient nor representative. However, it has provided some evidence to confirm that intonation is an important strategy to elicit the interaction in the discourse. For future research, we can investigate how and when the child acquires the functions of intonation from the interactions with the adults. References Chun, D. M. (1988). The neglected role of intonation in communicative competence and proficiency. Modern Language Journal, vol.72, pp.295-303. Chun, D. M. (2002). Discourse intonation in L2: from theory and research to practice. John Benjamins Publishing Company. Committee on psychosocial aspects of child and family health (1998). Guidance for Effective Discipline. Pediatrics, Vol. 101, No. 4, pp. 723 Escudero-Mancebo, D and Cardeñoso, V. (2006). Mining Intonation Corpora Using Knowledge Driven Sequential Clustering. Computer Science, Vol. 4140, pp.360-369 Gumperz, J. J. (1982). Discourse strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hsieh, H.Y. (2000). The Discourse-Pragmatic Functions of Final Particles in Taiwanese,(Master’ thesis, National Taiwan University). Retrieved from National Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations in Taiwan. Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Sociocultural theory and second language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lee,O. J.(2000). The Pragmatic and Intonation of MA- Particle Questions in Mandarin. (Master’ thesis, The Ohio State University). Retrieved from http://people.cohums.ohio-state.edu/chan9/ling/theses/Lee_OkJoo_MA_2000.pdf Li, I. (1998). Taiwanese Utterance-Final Particle HoNh-A Negotiation Begging Marker. Studies in English Literature and Linguistics,Vol, 24, pp.83-108. Li, I. (1999). Utterance-Final Particles in Taiwanese: A Discourse-pragmatic Analysis, Crane Publishing, Taipei, pp. 63-90. Masataka, N. (1992) Pitch characteristics of Japanese maternal speech to infants. Journal of Child Language,Vol.19. 213-223 Trainor, L. J., Austin, C. M., & Desjardins, R. N. (2000). Is infant-directed speech prosody a result of the vocal expression of emotion? Psychological Science, vol.11, pp.188–195. Thompson, J. (2006). Capturing Talk: Language Functions that Promote Pragmatic Competence. Paper presented at National Conference, American Educational Research Association. San Francisco. Warren-Leubecker, A., & Bohannon, J. N.(1984) Intonation Patterns in Child-Directed Speech: Mother-Father Differences. Child Development, Vol. 55, pp. 1379-1385. Wittmer, D. S., & Peterson, S. H. (Eds) (2006). Strategies to Encourage Language Learning, Strategies to Support Language Development and Learning. Infant and toddler development and responsive program planning. p. 183-187, 189. Yang, H. (1995). A pragmatic analysis of the BA particle in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics, Vol.23, No.2, 99-127.. Yang, L. C. (2010). Meaning and Use: A Pragmatic and Prosodic Analysis of Interjections in Conversational Speech, Paper presented at DISS-LPSS Joint Workshop, Tokyo.