Reflections on CERES (Consumers for Ethics in Research)

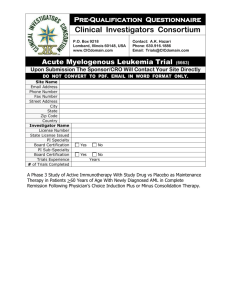

advertisement

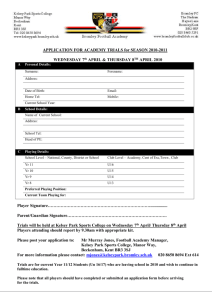

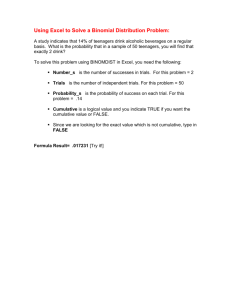

Reflections on CERES (Consumers for Ethics in Research) - Dr Naomi Pfeffer on the work of a pioneering organisation for research volunteers I’m now in an honorary capacity with Brian and Norma’s department, and I’m not only a social scientist; I’m a medical historian, and what I’m going to tell you now is medical history really. It’s been a stormy journey, hasn’t it? Some of you might know of CERES. It’s unfortunately called Consumers for Ethics in Eesearch. We used to agonize over our acronym, and it was established in 1988 as the Standing Committee of User Organizations for Pregnancy Childbirth and New Developments in Reproductive Technology. And I’m sorry Iain Chalmers isn’t here today, because it was thanks to him that the organization got off the ground, because when he was at the National Perinatal Epidemiological Unit in Oxford, he organized two big trials into pregnancy, and he involved representatives from the National Childbirth Trust and the Maternity Alliance and… gosh, I’ve forgotten the name. This happens when you get older: I can’t remember the name of Beverley Beech and Jean Robinson’s group. Anyway, another pregnancy group, who were to be involved in the trials. And it was a very innovative idea, a very pioneering idea. And from that CERES emerged. But we had a very different philosophy from, I think, how Iain originally conceived the role of patients. We were based outside of any kind of medical setting. It’s very interesting hearing all these presentations today, that you’re all kind of organized around some kind of clinical facility or a particular patient organization. We decided to take a much more generic viewpoint, to try and… because we were… a lot of the pioneers of CERES were active in the women’s health movement. We had a kind of consciousness-raising approach to what we were doing. We wanted to work with patient organizations and get them to take up the agenda, … and talk to their clinicians and whoever else was involved in the research, that was our idea. And at our initial meeting, as I say, we had 24 patient groups represented, patient organizations. And what we did was… I remember spending quite a lot of time going through the handbook of the Association of Medical Research Charities, and what the situation then was was that you’d have found that each medical charity would have a scientific committee, and it was very interesting how the same names featured in many of the organizations: these eminent scientists and physicians. And then they’d have a lay group who were basically the fundraisers, the people who ran the charity shops and the jumble sales and whatever, and raised the money for the scientists. And most of the research that was being conducted at the time when I looked through the handbook, was something to do with mice or something like that, cell biology or something like that: very little of it actually had relevance to the immediate concerns of the patient organizations. So our idea was to change all of this. And we weren’t anti research: we were for research, but we had a particular idea of research, of it being relevant, and also we were… many of us sat on ethics committees at the time, and we wanted it to be ethical as well. So we were a kitchen tableorganisation. None of us were paid. We raised money by small grants and through the sale of our publications, and I’ll show you some of what we did. OK, this is one of the first things that we did. At the time it was a kind of standard patient … Actually we cobbled this together from a whole lot of information sheets that we found at clinical trials; this is from one of your ethics committees. And this was the kind of way in which the people would be invited to take part in research. And another of our concerns was that it was impossible to communicate with the investigators. So you know nowadays you’d have a mobile phone, but I remember when I was sitting on these committees I would always try and phone up the number that the investigator had put, and invariably if you got through to anyone it would be an answer-phone. So these were the kinds of things that I think… I hope the world’s changed since then, but this is the world in the early 90s. And so one of the projects that we had, which was enormously successful if I say so myself. (I have to say that I’m terribly proud of CERES. When I prepared this talk, I would think how on earth did we ever manage to do all of this? We did it in addition to everything else we were doing.) So we produced this booklet - you can see it was funded by North-east Thames Regional Health Authority, which in itself is a historical monument – and this was advising investigators how to produce comprehensive, comprehensible patient information. It was very, very successful. I don’t know if any of you ever came across it in your time, but it was very widely used in training packs, and also allowed us to raise quite a lot of money. So then the other thing we did was we produced this leaflet, which was a model leaflet for people taking part in research, and all of our publications, we would send to the Plain English Campaign for them to read through to make sure that it wasn’t just us who thought it was understandable, but it generally complied with their standards, and we sold millions of these, and then it got re-done in this kind of thing, and we sold loads and loads. This is how we survived … it became standard practice I think for many investigators to use some of our information . We also produced this. We did this with the Royal Brompton Hospital at the time that their Ethics Committee was very concerned with trials into and around cystic fibrosis and about the kind of information that people were being given, so we produced a leaflet for them which again was widely used, but not as widely as ‘Medical research and You’. And then one of our other projects, which was enormously difficult and I was very proud of, was with Barts and the London Trust. We held focus groups and with various community groups in and around Barts and the London, and we reproduced our information taking on board the sort of things … their concerns, and we did it in various languages, and we also produced tapes. We produced tapes in English as well for people, because the level of literacy in the country is also quite low, so we had our information material on tape as well. This was very little-used, in fact, despite the fact that Barts and The London Ethics Committee sponsored it [laughter]. The people in the trust didn’t seem to know about it, but anyway. So why did we do the other activities? We held all these meetings. We held 24 meetings, public meetings with patient organisations, and we would always get patients to speak for us. Many of the things that you do now, we were pioneering; I have to say what we was very radical at the time. I particularly wanted to talk about this particular meeting because two things came out of it that were very interesting. One, it was very well-attended. People came from all over the country to attend it, and one of the things that came out of it was that there was a clinical trial going on at the time, I think it was into Sickle Cell, and people were very concerned because the patient information material was so poor. There had been a previous trial into a substance which had been very toxic. It proved to be very toxic, and the trial, the current trial was into a similar substance which had similar kind of name, which they hoped wouldn’t be as toxic. And the patient information leaflet didn’t actually engage with the different levels of toxicity, so people were very concerned about that, and it just once again highlighted the poverty of information that was being handed out by investigators at the time. And the other thing that came out of it was from people with sickle cell - that they wanted fewer studies into pharmacological substances. They wanted more into the kind of, social factors that would prevent them - that might prevent them going into crisis. So it was more that they wanted a social research, rather than clinical research. So those were the kinds of things that would come out at the meetings, and we would always publish our... we would always write it up in a newsletter. If anyone wants to see a CERES archive, I’m very happy to share it with people. I’m thinking of putting it in the Wellcome thing, but there are some in my house at the moment. This was a big conference that we had, A Voice for the Guinea Pig. Some of you may find that an objectionable term, So what else did I want to say? So we decided to close in 2006. The final nail in our coffin was the Parexel trial, because we found that the company, the facility was handing out ‘Medical research and You’ to people, which was completely inappropriate information for healthy volunteers. And we realised then that we were being... we were providing material that allowed investigators to claim that they were complying with all the regulations around the grand clinical trials. And we didn’t want that to be the case, we didn’t want to be seen to be sanctioning trials that we had no... we suddenly realised that we might be in danger of sanctioning trials that we had no knowledge of, and that worried us. But prior to that, we had, over the course of our existence - we were increasingly being contacted by research subjects who had had worries about trials that they’d either been invited to take part in, or they had been part of and that there’d been some problems about, and that there was no one for them to go to, to have their concerns taken up. There was no kind of organisation that had the expertise to support them through making their concerns known. And we didn’t have the resources at the time to do it, but it so happened that the draft of the EU Clinical Trials Directive - I don’t know how many of you have been unfortunate enough to read it at the time, but it did have in it, one of the clauses, one of the proposals was to have an independent voice for research subjects. And at the time, the Department of Health decided to support us to try and develop an advice and information service for research subjects. And we worked tirelessly on it, in trying to put it together, because it was a very complicated project. But then, no one told us at the last minute, that through - I don’t know what the pressures were, we had support from the ABPI, from various other prestigious organisations - but at the last minute, that particular clause was dropped, and so the whole scheme was a dead duck. NP What are the lessons? I’m going to shut up, the lessons are that, what we came up with, there’s no single research subject’s view, you know, it was very controversial at our public meetings. There’s no - we never came up with one, and I still haven’t heard it - agreement why you’re doing it. Why you should take note of research subjects, and I put forward these for you to think about. Is it for better science? That was one of the reasons put forward, that the science somehow would be improved by having... involving research subjects, that it would somehow be more ethical to have them, that you would have less subjectobject relationship. That it would facilitate, if the research was more user-friendly, that it would be easier to recruit the research subjects. That’s something else that’s put forward, and then you’ve had here today, there’s been more appropriate healthcare by having userinvolvement. Another one that I heard today, which I forgot to put on, was that it would help dissemination, that you put pressure on as the drug companies do, put pressure on healthcare providers to pay for whatever it is that you’ve just come up with. There again, the creation of new markets, that’s the point that I was making just now. And the one that we were most concerned with, that it would be confirming that they were complying with GCP or the other regulations, that they have to go through. And finally, I just know that what I think that we learned, is that there are enormous inequalities in power, that however you call people, participants, whatever you want to call them, you do eventually confront these enormous inequalities in power. And that however nice you are to [those in power] and whatever you want to call them, there’s nothing you can do about them, that they still won’t tell you that they’ve removed this clause from the draft of the EU Clinical Trials Directive. And finally, the landscape of clinical research changes, I mean, nowadays I think we’ve seen globalisation, restructuring, a whole lot of developments since CERES was in place. What you were talking about, Oonagh, has kind of, got much more elaborate now, with international companies having different sites all over. So what does it mean to have a patient voice in this kind of scenario? I’m sorry I’ve talked too long, but thank you very much.