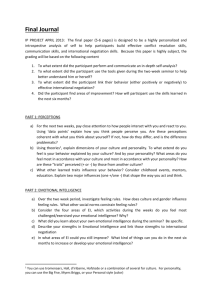

Effective Negotiation Course Program Development

advertisement