Chris Krause

advertisement

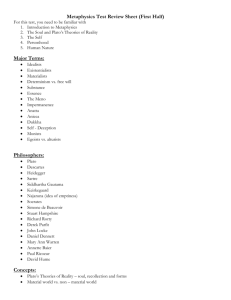

Krause 1 Chris Krause Prof. Z.A Starr PL11 13 March. 2006 Issues in Philosophy 1. The first response to Socrates is unsatisfactory because it simply provides a singular instance of impiety and not the standard that could be used to universally judge the piety of a said action. Giving a single example isn’t much good to Socrates; he wants to know what makes something impious, not just an instance of impiety. Socrates needs a scale to measure what is pious and what is not. The 2nd statement by Euthyphro is also unsatisfactory because we are defining what is already inherently (naturally) pious or impious within our own human ability to reason and judge – in other words, we are attaching the property of impiety or piety to an object which may be, already defined by the gods or by nature (logos), to be the contrary. When we judge holiness (piety); we approve or disapprove of something which already exists; our approving, by itself, does not make an action holy (pious). In other words, the holiness/piety comes BEFORE our judgment about it (More simply, something is pious or impious before we say it is) while in Euthyphro’s definition it comes AFTER the approval, becoming a consequence of the approval. 2. Plato is an immaterialist because he believed that existence is both empirical and immaterial (incorporeal), existing in a dualist state in which there is a world of forms (or ideas) beyond our senses, and the world of sense or our commonly Krause 2 held reality. Aristotle and is only concerned with and considers our physical world to be the only world, being perfect, and in which everything has a function, making him a materialist. To expand on this more, Plato believes there is no (or an unreliable portrayal) of material existence (consensus reality) and that there is only minds and ideas in those minds. The true world to Plato transcends our commonly held reality (Allegory of the Cave). Plato's metaphysics divides the world into two distinct aspects: the intelligible world of "forms", and the perceptive world we see around us, creating the concept of platonic or exaggerated realism. Plato says that the forms are entities in their true state, to which we cannot observe while we inhabit our human body, and may only experience after we transcend life and venture into death (Phaedo). Aristotle disagreed with this philosophy, instead arguing that everything is natural, tangible, scientific and perfectly meaningful and developed a pragmatic outlook on existence. In brief, Plato distrusted our known world and said there was something transcendent to it lying just beyond our ability to reason, Aristotle argued our commonly perceived (empirical) world is all we have and all we will ever have. 3. As said for #2 – Plato’s metaphysics can be summed up as metaphysical dualism where existence occurs in two “shades” of perception – the forms/ideas (true essence which we cannot reach while in our human shell) and perception through our senses. Heracleitus believed that all matter was in constant flux, that stability was an illusion and used fire as a metaphor to explain that the nature of existence is change itself summed up in his classic aphorism Panta Rhei: “Everything flows, nothing stands still.” He also introduced the concept of the Krause 3 logos or divine order, reason and logic, to which everything occurs perfectly, having a rational end and rational function. Heracleitus’ metaphysics are in direct contradiction to Parmenides who argued that everything is static, unchanging and ultimately eternal, summed up in the phrase "nothing comes from nothing." Parmenides, who argued for the unity of all things, had a large influence on Plato’s concept of the soul. According to Plato, every-thing that man perceives with his senses is only a quite imperfect copy of the "forms" which are said to be eternal – this also coming from the rational of Parmenides. Plato conversely argued that our world of sense is in constant flux, much like Heracleitus would have argued. In conclusion considering the metaphysics of Plato, the world of sense can represent the metaphysics of Heracleitus while the world of forms can represent the metaphysics of Parmenides. 4. a. Anaximander, in direct contradiction to the King James Version of the bible argues that there had been a primordial mass at the beginning of time. The Speiser translation of the bible also details a similar story of creation. From this primordial mass (apeiron) came the world, says Anaximander. This mass was pure entropy, subject to nothing, which perpetually supplied new materials, embraced opposites and directed the movement of things. Out from this mass, our earth, a cylindrical drum emerged, suspended equidistant from orbs of fire, which had originally wrapped around it like “bark round a tree.” From this chaos came the world as we know it, and life, by similar transmutations. Unlike biblical Krause 4 creation, Anaximander argues that life evolved from primitive forms, probably aquatic, to eventually produce the life we see around us today. Although some obvious similarities surface when comparing Anaximander to biblical creation story – there is also some glaring inconsistencies. The bible states that within 6 days humanity was created after the other organisms on the earth were created by god, Anaximander refrains from setting a timeframe to his creation and instead says that life gradually became what it is today, that man was not special in that he evolved from the same primordial soup that everything evolved from. In this regard, Anaximander is markedly scientific and philosophical as opposed to mythical and dogmatic in his consideration of creation. b. The E.A Speiser translation of Genesis is more like Anaximander’s and other pagan depictions of creation. Speiser translates that existence before Earth was a formless waste, much like the Apeiron, while the King James edition argues that the world was “void” and “without form” before Earth was created. This is a significant point because it clearly shows a direct evolution from Greek (or more generally, pagan) thought to biblical thought in the Speiser translation and makes it clearer where the Hebrews got their ideas from. In the Speiser translation, god commands wind to go over the surface of the primordial waters, the “spirit of god” is not mentioned, drawing another pagan elemental connection – as would be had in Anaximander’s creation. Speiser’s translation is much more similar Krause 5 to Anaxiamander’s creation; the King James Version is more abstract, imprecise and ambiguous in both terminology and meaning. 5. a. To Plato the world of perception (consensus reality) is not inherently true and obscures the more honest, fundamental essence of reality which is the world of forms or ideas that lies beyond our senses. To Plato considering the perceptive world, things are never as they seem, and we must carefully not only distrust our senses but scrutinize everything we are exposed to, as we would unravel an onion to get to the center. For Plato our world we know isn’t real, it’s just a façade to blind us from the ultimate truth which is the form of what were exposed to. b. In the Allegory of the Cave we have a setup like such: People (the human race) are shackled to a wall and must look forward, all they see is shadows of objects illuminated by a fire in the back of a cave. In this way, the human race can only see a distorted, illusory, perceptual depiction of the true essence of things (form/idea). What we appear to see is all we have known for our entire life without philosophy. We never question Krause 6 the cause of what we see, as would not the people shackled to the wall. Supposing one of the people escapes his shackles and sees existence as it really is he wouldn’t be accepted among humanity any longer and actually be ostracized (this is a subtle reference to Socrates’ forced suicide at the hands of the Athenian government), so he transcends to the outside world where he experiences a lush pasture, reflections of himself in water, and the sun. The sun is the ultimate truth, the ultimate illuminator to which no greater illumination can come before, representative of the soul (psyche), the highest reason that is inherent to every person. 6. In Aristotle’s methodology change is the agent and its action which spirals an entity toward its end, or good. According to Aristotle all change is subject to 4 primary causes, or why it was subject to change. The Material Cause is that form in which things are comprised of its parts, constituents, substratum or materials. This reduces the explanation of causes to parts forming the whole entity. The Formal Cause defines what a thing is by declaring that anything is determined by the form of the whole or archetype. It states that the whole is the cause of its parts. The Efficient Cause is that which change or the end of change first begins. It explains why things are set in an active as opposed to a passive state and explains why things are in movement, at rest or in a current state of change. The Efficient Cause is perfectly represented in the domino effect, when you (the Efficient Cause) push a domino, it falls over; the domino wouldn’t fall over on its own without something causing change. The Final Cause is an entity’s purpose, function or use but more importantly why it exists at all. To Aristotle, everything Krause 7 has a purpose in existence and nothing exists without meaning or design. The Final Cause asks what purpose something is supposed to serve. An example: the four causes of man: 'What is it made from?' 'Flesh and so on' (material cause); 'What is its form or essence?' 'A two-legged creature capable of reason (say)', (formal cause); 'What produced it?' 'The father (on Aristotle's biology)' (efficient cause); 'For what purpose?' 'To fulfill the function of a man (roughly meaning 'to live a life in accordance with reason') (final cause) 7. a. The goal of Socrates was to become wise and honest. Socrates’ journey through life and death was a quest to understand things he was ignorant to, without pretension, to become fully honest and truthful to himself, claiming knowledge of nothing and claiming expertise in nothing. Kaufmann similarly declares this is the single aim of philosophy: to become honest. Through finding faults in our own personal logic and beliefs through Socratic dialogue we can carefully scrutinize everything we perceive and hold to be true we become true philosophers and true human beings. Socrates claimed no belief too precious to be discarded at a moment and held nothing absolute, always seeking further glimpses of truth and understanding, and never claiming to be a sage or even a philosopher. Ironically, in doing so, he became the ultimate example of a virtuous philosopher. Krause 8 b. When we use labels in dialogue we stop thought because we cease to discuss the ideas themselves and instead discuss the subjective, personal interpretation of a word, which gets us no where. Labeling does produce some rapidly amusing “debates” on republican propaganda channels such as Fox News where sensational terms like “bleeding heart liberal,” “terrorist” and “compassionate conservative” are thrown around casually with no consideration or definition. Instead of blurting out an ambiguous label and assuming everyone is thinking the same thing we are, we need to take our time, discuss the issues behind the label and deduce the essential nature of all words. What does it mean to be a “terrorist” or a “christian” or a “Buddhist” – what do you actually believe? This is terribly important, what you believe, not what the engineers of a word believe, and in they believing, instill beliefs in you without a proper thought process of consideration occurring. 8. Anaximander’s explanation of the origin and evolution and structure of the universe is available in #4. Thales much like other ancient Greek philosophers distrusted divine explanations for natural phenomenon like earthquakes, tidal waves, meteor showers etc (And by extension, creation) and instead attributed to them natural causes. Although Thales was mostly incorrect in his assertions about the cause of such events he is considered the first philosopher because he began to look at things scientifically, rationally and objectively instead of by myth. This being said, Thales attempted to explain the origins of our world from an elemental (proto-scientific) as opposed to a mythological way. Thales declared that the principle element is water and everything Krause 9 must come from water. "For it is necessary that there be some nature, either one or more than one, from which become the other things of the object being preserved ... Thales says that it is water” and “"water constituted the principle of all things" says Aristotle in his Metaphysics – the source to which we are most familiar with Thales. Heraclitus Homericus explains that Thales came to this conclusion after seeing condensation turn into air, slime and finally earth. The Earth argues Thales, was once suspended in a all encompassing ocean, and then the water solidified into soil creating the world we know today. Anaximenes also explained creation and our origins in an elemental way – declaring that the principle element was not water but air, and that everything we know came from air. He argued that everything is air at different densities, velocities and temperatures. In this way Earth was formed from a broad disk of earth, floating on the all encompassing air. Similar condensations produced the sun and stars; and the flaming state of these bodies is due to the velocity of their motions. Anaximenes’ cosmogony can be summed up in "Just as our soul, being air, holds us together, so do breath and air encompass the whole world."