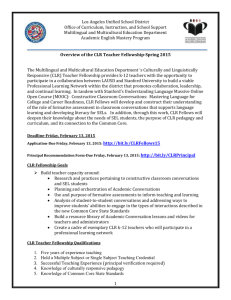

INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS

advertisement

INDIVIDUAL RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS s51(xxxi): Acquisition of property on just terms The acquisition of property on just terms from any State or person for any purpose in respect of which the Parliament has power to make laws. o Both a power and constitutional guarantee: Bank of NSW v Commonwealth (1948) o Grace Bros Pty Ltd v The Commonwealth (1946) 72 CLR 269: Dixon J: “the condition “on just terms” was included to prevent arbitrary exercises of power at the expense of a State or a subject”. o “in which the P has power to make laws” every law must ALSO be supported by at least one other legislative power: P J Magennis Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1949) 80 CLR 382 Limitations: o Does not stop States from acquiring property on a compulsory basis: Pye v Renshaw (1951) 84 CLR 58 o Does not stop C from acquiring property in Territories: Teori Tau v Commonwealth (1969) 119 CLR 564. This view doubted: Newcrest Mining (WA) Ltd v Commonwealth (1997) 190 CLR 513. DOES apply where law is also validated by another head of legislative power (besides s122): Newcrest. o Does not apply where terms of OTHER legislative power manifests an intention which precludes its operation: Nintendo Company v Centronics Systems (1994) 181 CLR 134. o Circuit Layouts Act 1989 (Cth) removed copyright protection of integrated circuits and replaced with special regime of protection. o “operation of s 51(xxxi) to confine content of other grants of legislative power…is subject to a contrary intention…in particular, some…clearly encompass the making of laws providing for the acquisition of property unaccompanied by any quid pro quo on just terms” o Some traditional exceptions eg. taxation laws and pecuniary penalties (forfeiture of property for offence): Trade Practices Commission v Tooth & Co (1979) 142 CLR 397. o “If the circumstance sare such that the notion of fair compensation…is irrelevant or incongruous, the law is not a law with respect to s 51 (xxi)”: Airservices Australia v Canadian Airlines (1999) 202 CLR 133: law impose lien on aircraft to ensure payment of statutory charged reasonably related to reg of air navigation. Property: Given full and flexible operation: Bank of NSW v Commonwealth (1948): Bank of NSW challenged Fed law which allowed Commonwealth Bank (agent of Fed Gov) to acquire the business of private banks. o Dixon J: proprietary interest is capacity to exercise real and effective control of property. Minister of State for the Army v Dalziel (1944): National Security Regulations gave C power to exclusive possession of any land for indefinite period and gave Minister power to determine amount of compensation to affected owners. C acquired D’s land for defence purposes. o Property includes: “every species of valuable right and interest including real and personal property, incorporeal hereditaments such as rents and services, rights of way, rights of profit or use in land of another and choses in action” Health Insurance Commission v Peverill (1994): P (doc) made claims under Medicare scheme for services he performed on basis of schedule of charges under Health Insurance Act 1973 (Cth). P passed law with retro effect that reduced amounts payable for services. P argued that it was compulsory acquisition of property. o Does NOT include statutory interests o “statutory entitlements to receive payments from consolidated revenue which were not based on antecedent proprietary rights recognised by the general law” Acquisition: Involves compulsion (Poulton v Commonwealth (1953) 89 CLR 543), as distinguished from agreement (John Cooke & Co v Commonwealth (1924) 34 CLR 269). Distinct from deprivation: Mutual Pools & Staff v The Commonwealth (1994) 179 CLR 155. o “the extinguishment, modification or deprivation of rights…does not itself constitute an acquisition” o “there must be an obtaining of at least some identifiable benefit or advantage relating to the ownership or use of property” Newcrest Mining (WA) v Commonwealth (1997) 190 CLR 513: C law expanded Kakadu National Park extinguished N’s rights to carry out mining of minerals. C left with possession of minerals on/under land identifiable advantage. Does not have to be C (or its agent) to be the acquirer. May be acquired by someone else for purposes of the C: McClintock v Commonwealth (1947) 75 CLR 1. Just terms: o Terms are not unjust merely because the ordinary principles of compensation have been altered, departed or limited. “Law must be so unreasonable as to terms that it cannot find justification in the minds of reasonable men”: Minister of State for the Army v Dalziel (1944) 68 CLR 261. o Usually determination based on market value will be sufficient. But court is in o way restricted to market value: Nelungaloo Proprietary v The Commonwealth (1946) 75 CLR 495: P argue that measure of compensation be compared to that available on free market. o “neither…involves a complete exclusion of all consideration of the interests of the community, or, more particularly, the laws which protect such interests” o Take into account peculiar value of property. o Johnston Fear & Kingham v Commonwealth (1943) 67 CLR 314: acquisition of 3 colour offset press electronic printing machine. o “just compensation…depends upon these circumstances….In the case of goods which a person uses in his business, the price might fall below fair compensation if the machine could not be replaced without long delay”. o “there are cases in which the payment of a “price” for goods…does not provide a just measure of compensation”. o Determined by impartial tribunal: Nelungaloo v Commonwealth (1948) 75 CLR 495. o Determinations are amenable to judicial review: Australian Apple and Pear Marketing Board v Tonking (1942) 66 CLR 77. o Take into account interests of property owner and community in acquisition. o Grace Brothers v Commonwealth (1946) 72 CLR 269: Fed land acquisition law nominated that just terms compensation be assessed at date BEFORE the date of acquisition – held valid. o Latham CJ: “justice involves consideration of the interests of the community as well as of the person whose property is acquired”. o At time, effective prosecution of the WWII required efficient use of public money just terms assessed in this context. o Just terms – not monetary equivalent fairness. s80. Trial by jury The trial on indictment of any offence against any law of the Commonwealth shall be by jury, and every trial shall be held in the State where the offence was committed, and if the offence was not committed within any State the trial shall be held at such place or places as the Parlia-ment prescribes. Does not apply to the States or Territories Applies to “any law of the Commonwealth” – thus, does NOT apply to State and Territories law. Byrnes v The Queen (1999) 199 CLR 1 at 32 per Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Callinan JJ, at 39 per Kirby J. Does not apply in the Territories – laws made under s122. R v Bernasconi (1915) 19 CLR 629 - criticized in Spratt v Hermes. Proposition that Ch III applies to Territories raised in: NT V GPAO (1998) case and North Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid v Bradley (2004) BUT Bernasconi still good law. Does not extend to Courts martial Re Tyler & Ors; Ex parte Foley (1994) 181 CLR 18: held C power to make laws with respect to defence and incidentally military discipline not subject to guarantee of s80. Deane, Gaudron JJ (dissenting): that judgment is inconsistent with separation of judicial power in Ch III to give power to military tribunals to try/punish armed forces for offences, which were same as offences under general law. Proceedings “on indictment”: Involve formal setting out of charges against the accused on oath by rep of Queen before grand jury. s80 is NOT a guarantee of trial by jury in cases involving serious offences (literal approach). Literal approach: Results in narrow field of operation. Enables C to circumvent right to “trial by jury” by providing offences be tried NOT on indictment. This view criticised many times: Kingswell v The Queen; but not doubted (still good law). Used in R v Archdall and Roskruge; Ex parte Carrigan and Browne (1928) 41 CLR 128: two union officials separately charged (in summary proceedings) with offences against Crimes Act 1914 (Cth) relating to organising strikes. Conflicting provisions in Crimes Act and Acts Interpretation Act 1904 (Cth). Former said summary jur court cannot impose imprisonment for over 1 yr. Latter said offences that are punishable by over 6 mths imprisonment indictable offence! A’s argued they were under AIA trial by jury. And to ascertain what was “indictable offence”, must have regard to law at time of Constitution. THUS: if regarded as indictable at that time cannot be declared NOT by the P. Rejected! “The suggestion that the P, by reason of s80 of the C, could not validly make the offence punishable summarily has no foundation and its rejection needs no exposition” Higgins J: in reading s80 it states “if there be an indictment, there must be a jury; but there is nothing to compel procedure by indictment”. THUS: C has legislative discretion to determine whether Fed offences are tried summarily or on indictment; ie. Whether to grant/remove the right to trial by jury. Confirmed in Cheng v The Queen (2000) 203 CLR 248 at 292, McHugh J: “The words of s 80 were deliberately and carefully chosen to give the Parliament the capacity to avoid trial by jury when it wished to do so” At time of Federation: “indictment” was procedure usually for “serious offences”. THUS: proposition that Fed offences of serious nature or with serious penalties s80 applies: Kingswell v The Queen (1985) 159 CLR 264 at 310–311. BUT has not had majority support of the HC yet. Right to trial by jury cannot be waived by the accused Literal: “SHALL be trial by jury” A does not discretion to waive right. Confirmed in Brown v The Queen (1986) 160 CLR 171: B charged with Fed drug offences and tried on indictment. B elected not to have jury and trial judge ruled that s80 disabled A from making that election. Appeal to HC: agreed – right cannot be waived. o Literal approach – provision REQUIRES that proceedings on indictment for C offences use trial by jury. o It is a RIGHT not a priviledge: Deane J at 201. Content of the right – historical approach: Phrase “trial by jury” HC has adopted an historical approach Confirmed in Cheatle v The Queen (1993) 177 CLR 541: challenged provisions of Juries Act 1927 (SA) which provide for majority verdicts (10 or 11 out of 12) where at least 4 hrs of deliberation there was still not a unanimous verdict. Argued that under s80, any conviction must be by unanimous jury. o Unanimous jury verdicts had been required in CL since 14th C and heavily weighted by authority. o SA argued against historical approach: in 1900, the members were 12 in number, male, had significant property qualification etc. “Neither history nor concepts of substance and procedure provide a sound basis for deciding which of those features can be discarded. It could not have been intended that all those features were immutable”. o HC (unanimous, rejected): “to abrogate the requirement of unanimity involves and abandonment of an essential feature of…trial by jury. In contrast, a liberalization of the qualifications of the jurors involves no more than an adjustment…to conform with contemporary standards and to bring about a situation which is more truly representative of the community”. HC (unanimous) held s80 interpreted in accordance with CL history of criminal trial by jury at Federation, but then adapted to contemporary standards at 552. s80 does not require a jury of 12 Brownlee v The Queen (2001) 207 CLR 278: challenged provisions of Jury Act 1977 (NSW) which let jury cannot on if juror died/discharged so long as 10+. B argued that (historically) must have 12 jurors. o Essential features of trial by jury: independence, representativeness and randomness of selection. o No constitutional requirement that jury be 12 members. But no conclusion about min no. o Callinan J at [184]: “There is no reason in principle why a jury of twelve persons should necessarily be considered more representative of the community than a jury of ten persons or fourteen, although there may come a point at which a somewhat smaller number could not, in any real sense, be regarded as a jury, a matter that is unnecessary to decided in this case” Section 116 — freedom of religion The Commonwealth shall not make any law for establishing any religion, or for imposing any religious observance, or for prohibiting the free exercise of any religion, and no religious test shall be required as a qualification for any office or public trust under the Commonwealth. Does not apply in the States, despite appearing in the chapter The States: Attorney-General for Victoria; ex rel Black v The Commonwealth (the DOGS case) (1981) 146 CLR 559 Application to laws under s122 (Territories power) uncertain. o Lamshed v Lake (obiter): no reason why s 116 should not apply to laws made under s 122. o Approved in Kruger v The Commonwealth What is a ‘religion’? Necessary to define ‘religion’, which is a “difficult, if not impossible” task: Jehovah’s Witnesses case, 67 CLR at 123. Has been WIDELY interpreted. Church of the New Faith v Commissioner for Pay-Roll Tax (Vic) (the Scientology case) (1983) 154 CLR 120: question whether Church of the New Faith, Scientology, was exempt from State pay-roll tax legislation on basis it was religion. Mason ACJ and Brennan J at 136 – TWO FOLD TEST “For the purposes of the law, the criteria of religion are twofold: first, belief in a supernatural Being, Thing or Principle; and second, the acceptance of canons of conduct in order to give effect to that belief, though canons of conduct which offend against the ordinary laws outside the area of any immunity, privilege or right conferred on the grounds of religion. Those criteria may vary in their comparative importance, and there may be a different intensity of belief or of acceptance of canons of conduct among reli-gions or among the adherents to a religion. The tenets of a religion may give primacy to one particular belief or to one particular canon of conduct. Varia-tions in emphasis may distinguish one religion from other religions, but they are irrelevant to the determination of an individual’s or a group’s freedom to profess and exercise the religion of his, or their, choice” Wilson and Deane JJ 173-4 (identified FIVE INDICIA – not rigid!): 1. Belief in the supernatural…reality extends beyond that which is capable of perception 2. Man’s nature and place in the universe and his relation to things supernatural 3. Adherents as requiring or encouraging them to observe particular standards or codes of conduct or to participate in specific practices having supernatural significance 4. However loosely knit or varying in beliefs and practices…they constitute an identifiable group 5. The adherents themselves see the collection of ideas and/or practices as constituting a religion Murphy J at 151: WIDE TEST “The better approach is to state what is sufficient, even if not necessary, to bring a body which claims to be religious within the category. Some claims to be religious are not serious but merely a hoax, but to reach this conclusion requires an extreme case. On this approach, any body which claims to be religious, whose beliefs or practices are a revival of, or resemble, earlier cults, is religious. Any body which claims to be religious and to believe in a supernat-ural Being or Beings, whether physical and visible, such as the sun and the stars, or a physical invisible God or spirit, or an abstract God or entity, is reli-gious. For example, if a few followers of astrology were to found an institution based on the belief that their destinies were influenced or controlled by the stars, and that astrologers can, by reading the stars, divine these destinies, and if it claimed to be religious, it would be a religious institution. Any body which claims to be religious, and offers a way to find meaning and purpose in life, is religious. The Aboriginal religion of Australia and other countries must be included. The list is not exhaustive; the catego-ries of religion are not closed” The ‘establishment’ clause – “shall not make any law for establishing any religion” Attorney-General (Vic); ex rel Black v Commonwealth (the DOGS case) (1981) 146 CLR 559: C passed State Grants Acts, which gave financial assistance to States subject to condition. Included that portion of money be given to non-gov schools (usually religions). Argued that they gave financial support to religions (establishing religion) AND gave pref sponsorship to 1+ religion over others. 1st argument: establishing religion via financial support o Maj: dismissed – provision of financial assistance did not “establish” a State religion. o Clause referred to laws “intended and designed to set up the religion as an institution of the C”: Barwick CJ at 583; o Laws with “the purpose and effect of setting up any religion as a state church”: Gibbs with Aickin J agree. o Laws which effected the “authoritative establishment or recognition by the state of a religion or church as a national institution”: Mason J at 616 o Law which provided “statutory recognition of a religion as a national institution”: Wilson J 2nd argument: pref support, favours, titles and advantages to one religion o Maj: rejected. o Sponsorship “must be of so special a kind that it enables us to say that by virtue of the concession the religion has become established as a national institution” Religion observance: No HC decisions consider this clause. Murphy J (dissenting) in R v Winneke; Ex parte Gallagher (1983) 152 CLR 211: Fed law requiring witness at Royal Commission to swear an oath. o Argued that it infringed s116. o “may lawfully decline to take an oath and lawfully decline to state why he declines to take an oath”. The free exercise of any religion – “prohibiting the free exercise of any religion” Krygger v Williams (1912) 15 CLR 366: defence leg imposed obligation to swear oath of military service. K objected to oath as contrary to Christian beliefs. HC: disagreed. o Griffith Cj: prohibit the doing of acts which are done in practice of religion. o To require a man to do a thing which has nothing at all to do with religion is not prohibiting him from a free exercise of religion. It may be that a law requiring a man to do an act which his religion forbids would be objection-able on moral grounds, but it does not come within the prohibition of sec 116: at 369. CF: Judd v McKeon (1926) 38 CLR 380. Higgins J held: elector’s abstention from voting on religious grounds was a valid reason for failing to vote. Extends to the toleration of absence of religion – trying to convert ppl is bad! Kruger v The Commonwealth (1997) 146 ALR 126 at 232, Gummow J: Action in pursuance of a particular religious belief that is both monotheistic and eager to proselytise may conflict impermissibly with toleration both of religion and of an absence of religion. Adelaide Company of Jehovah’s Witnesses v The Commonwealth (1943) 67 CLR 116: freedom guaranteed by s 116 is NOT absolute, o subject to limitations…such as are reasonably necessary for the protection of the community and in the interests of social order: Starke J. o “Freedom of religion may not be invoked to cloak and dissemble subversive opinions or practices and operations dangerous to the common weal”: Rich J. “any law FOR…” “A law must have the PURPOSE of achieving an object s 116 forbids”: A-G (Vic); Ex rel Black v Commonwealth (1981); Kruger v The Commonwealth (1997). THUS: does not prevent the C from enacting law which has unintended incidental effect of infringing s116: Minister for Immigration and Ethnic Affairs v Lebanese Moslem Association & Ors (1987): Implied Freedoms Text and structure of Constitution – system of representative and responsible gov gives rise to implied freedoms from gov power. Representative government as a basis for the implication of freedoms from governmental power Limit on implications to be drawn from “representative democracy”. McGinty v Western Australia (1996) 186 CLR 140: M and others challenged provisions of WA Constitution and electoral laws that gave rural electors more voting power than metro electors. Argued inconsistent with rep democracy of one vote – one value. o Rejected by maj of HC: neither Constitutions give rise to implication of guarantee of “one vote – one value”. o McHugh J: “I regard the reasoning in Nationwide News, Australian Capital Television, Theophanous and Stephens in so far as it invokes an implied principle of representative democracy as fundamentally wrong and as an alteration of the Constitution without the authority of the people under s 128 of the Constitution… “To decide cases by reference to what the principles of representative democracy require is to give this Court a jurisdiction which the Constitution does not contemplate and which the Australian people have never authorised….asking the justices of this Court to determine what representative democracy requires. That is a political question and, unless the Constitution turns it into a constitutional question for the judiciary, it should be left to be answered by the people and their elected representatives acting within the limits of their power as prescribed by the Constitution.” o Also seen in: Langer v Commonwealth (1996) 186 CLR 302: L challenged provision of Electoral Act 1918 (Cth), which prohibited the encouragement of voters to exercise of right of choice in Con. Also infringed implied constitutional freedom of communication on political matters. o Held: rejected. Did not infringe freedom as L was able to criticise the system, just not allowed to encourage people to discourage system. Implied freedom of speech to discuss matters of political or governmental concern o Majority recognition in: Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills (1992) 177 CLR 1: validity of Fed industrial relations leg provision that made it offence to use words calculated to bring member of Aus Industrial Relations Commission into disrepute. o Held: provision was unconstitutional. o Curtailment of freedom of speech was disproportionate to s51(xxxv). o HELD: system of rep gov prescribed by Con gave rise to an implication that it is necessary to enable the discussion of political and governmental affairs! o Confirmed (maj) in: Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106: challenge Fed broadcasting leg which prohibit certain types of political advert during election periods. o Held: unconstitutional – 6 judges. o Implication drawn in different ways uncertainty of scope of freedom. o Theophanous v Herald & Weekly Times Ltd (1994) 182 CLR 104: letter in Sunday Herald Sun (Melb) which was critical of P’s views on immigration policy. P (member of Fed P) sued D in defamation. D argued protected by implied freedom. o Maj recognised it as a defence to defamation – and its limits! Implied right to publish material about government/political matters, members of P, suitability of persons for P. In light of above freedom, publication will not actionable in defamation if D established that it was unaware of falsity of material, did not publish recklessly and pub was reasonable in circumstances. o THUS: broad implied freedom based on principles of representative democracy, which were “necessary” to sustain a rep dem. o HC activism? o Stephens v West Australian Newspapers Ltd (1994) 182 CLR 211: affirmed above and also arose from WA Constitution applies to State political matters. o What are the limits to finding such implications? Read above!! Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997) 189 CLR 520: o FACTS: P (NZ P and former PM) brought defamation against ABC. ABC defended included freedom. o HC: “Since McGinty it has been clear… that the Constitution gives effect to the institution of “representative government” only to the extent that the text and structure of the Constitution establish it. In other words…the Constitution provides for that form of representative government which is to be found in the relevant sections. Under the Constitution, the relevant question is not, “What is required by representative and responsible government?” It is, “What do the terms and structure of the Constitution prohibit, authorise or require?” o In McGinty, Gummow J: to draw implications from a ‘doctrine of representative democracy’ was to ‘adopt a category of indeterminate reference’: 186 CLR at 269. Lange Test o Freedom is not absolute limited to what is necessary for the effective operation of that system of representative and responsible government provided for by the Constitution. Does the law effectively burden freedom of communication about government or political matters either in its terms, operation or effect? If the law effectively burdens that freedom, is the law reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve a legitimate end in a manner which is compatible with the maintenance of the constitution-ally prescribed system of representative and responsible government? If YES and then NO invalid: Lange. o Levy v Victoria (1997) 189 CLR 579: L (animal rights activist) charged with entering duck hunting area without license. Argued that infringed freedom of speech – capacity to protest made it necessary to access hunting grounds to retrieve birds so he could show to TV crews. Held: laws were reasonably necessary to protect safety of public and participants. Burden on communication was reasonably appropriate and adapted to the legitimate end o Coleman v Power [2004] HCA 39: C handed out pamphlets about corruption of members of police. P asked for pamphlet and C yelled that P was a corrupt policeman. C arrested for “insulting language” under Vagrants Act. Argued freedom of speech. Held: C won. McHugh: struck down law as it was “without a qualification” Gummow and Hayne JJ: upheld law if interpreted to have a restricted operation “it does, however, have a more limited operation” Kirby: upheld law as it is compatible. Types of communications not restricted to politicians, parliaments and elections applies to corruption of police (public servants and other instrumentalities of commonwealth, state and local governments) Also included insults: “From its earliest history, Australian politics has regularly included insult and emotion, calumny and invective, in its armory of persuasion...” Modified Lange test “in a manner” looks at whether means are reasonable. Gleeson CJ (dissenting) favoured a more strict test: “the court will not strike down a law restricting conduct which may incidentally burden freedom of political speech”. THUS: invalid only if law’s direct purpose is to restrict political communication. o APLA Limited v Legal Services Commissioner (NSW) [2005] HCA 44: Legal Profession Regulation 2002 (NSW) provision prohibit advertising of personal injury legal services. Argued infringement of freedom. Rejected. Gleeson CJ and Heydon J stated: "The possibility that [the Regulation’s] advertisement might mention some political or governmental issue, or might name some politician, does not mean that the regulations infringe the Constitutional requirement. The Regulations do not prohibit ... communications about government or political matters. They prohibit communication between lawyers and people who, by hypothesis, are not their clients, aimed at encouraging the recipients of the communications to engage the services of lawyers. Such communications are an essentially commercial activity." Application of Lange principle to CL defence of qualified privilege in defamation: Roberts v Bass (2002) 212 CLR 1: Roberts authorise publication of materials to persuade voters not to vote for Bass, suggested that Bass corruptly used position for holidays. R won. Defence of qualified privilege: person has duty in making a statement and recipient has corresponding duty in receiving it. Traditionally unavailable to mass audience. Gaudron, McHugh and Gummow JJ: “Communications…are privileged because their making promotes the welfare of society. But the privilege is qualified…by the condition that the occasion must not be used for some purpose…foreign to the duty…” Lange: HC developed it so that: o Protect people communicating to electors about qualities of P candidates etc. o Extended to mass audience communication so long as is reasonable o Not actuated by malice. Other Implied Freedoms Arising from system of representative and responsible government. Implied right of access to the seat of Government: Crandall v Nevada 73 US 35 (1867); Cunliffe v The Commonwealth (1994) 182 CLR 272 at 328 per Brennan CJ. Freedom of association and travel associated with the election of Federal representatives and associated activities: Kruger v The Commonwealth (1997) at 195–197 per Gaudron J, at 218 per McHugh J. Gaudron J at 196: “just as communication would be impossible if “each person was an island”, so too it is substantially impeded if citizens are held in enclaves, no matter how large the enclave or congenial its composition. Freedom of political communication depends on human contact and entails at least a significant measure of freedom to associate with others. And freedom of association necessarily entails freedom of movement” BUT these freedoms have not been approved by majority of the HC in the ratio of any decision. Gummow J at 229: “The problem is in knowing what “rights” are to be identified as constitution­ally based and protected, albeit they are not stated in the text, and what methods are to be employed in discovering such “rights”. Recognition is required of the limits imposed by the constitutional text, the importance of the democratic process and the wisdom of judicial restraint.”