Code mixing and code switching of Romanian

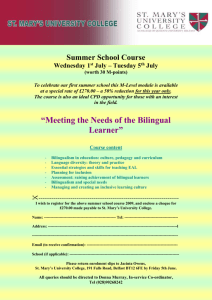

advertisement

Code mixing and code switching of Romanian-Hungarian bilingual communities in Transylvania Abstract The following paper will highlight the linguistic peculiarities of bilingual communities of Transylvania, namely the Hungarian minorities. Focus will be assigned to the phenomena of code mixing and code switching. Given the number of distinct opinions in the linguistic community on the phenomena, an all agreed upon definition is not yet available; thus, the different points of view will be discussed and analyzed based on examples. The examples given are abstracted from recorded conversations of bilingual speakers. Based on these observations the reader of this paper should be able to construct a global image on the phenomena. Introduction In linguistic settings, the usage of the term ‘bilingualism’ is starting to gain exhaustion. Speaking more than one language has proved to be a global phenomenon. In all corners of the world the English language has gained an impressive amount of speakers. The emergence of the English language as a global language had a few social and linguistic consequences, one of these being bilingualism. Automatically, in order to maintain a connection to the industrialized and modern global system, speakers were required to be proficient in the use of English. Such a setting instantly creates a situation in which bilingualism will emerge. To give an example, in her book: Multiple Voices. An Introduction to bilingualism (2006), Carol Myers-Scotton provides the reader the following portrait of a bilingual speaker: “Zhao Min speaks two dialects of Chinese as well as English. He’s a commodity trader for a joint venture of the government of the People’s Republic of China and an international conglomerate. He comes from Nanjin, China, but divides his time between Beijing and Hong Kong in China, with extended stays in Europe. He studied English as a part of his secondary schooling and university education. Today his job demands a great deal of English; he writes emails and has long-distance phone conversations – always in English- with his customers, from whom English is usually a second language, too (e.g. Serbs in former Yugoslavia, now Serbia). When he visits his family in Nanjin, he speaks his home dialect, but when he deals with Chinese colleagues, he speaks the standard dialect of the People’s Republic of China (formerly called Mandarin, a name some still use, but called Putonghua in the PRC). This is the variety he speaks with his wife, who was raised in Beijing. Zhao Min has little spare time from his job, but when he does, he often watches films, and has a huge collection of Englishlanguage movies on DVD.” (Scotton, 2006: 1) Based on this portrait, a few observations can be made on the nature of bilingualism. First of all, bilingualism highly depends on social and industrial requirements: social setting (his business associates also speak English as a second language), job requirements (a trader and international conglomerate needs to share a language with customers, international associates, in this case English), education (Zhao Min studied English, an institutionalized variety of the language, in a formal setting), family (due to his wife’s influence he uses a variety of the Chinese language next to the formal one). Secondly, the geographical area is also important: in his native area he learned a dialect of Chinese language, due to his marriage and job he also needed to acquire fluency in Mandarin Chinese. It can be stated that the English language has the ability to connect people for various reasons in spite of physical distance and social background. The last observation that can be made is the type of self-education of the bilingual in question: watching movies in English helps develop and improve his pronunciation and vocabulary. This type of education is different from a language learning experience in school or college, because it takes place in an informal setting, thus, the language acquirement process is natural. Bilingual in Transylvania Taken into account the above detailed portrait of a bilingual, the following generalizations can be made when describing the portrait of a Transylvanian bilingual. Usually, the major minority in Transylvania are Hungarians. These Hungarians are different from the Hungarians living in Hungary, their name is ‘Szekely’ with regards to ‘Magyar’ as being the name for Hungarians living in Hungary. Due to historical occurrences the two nations developed different characteristics. In what follows, the description will refer to Hungarians living in Transylvania. Based on the famous controversy with the region of Transylvania, the social characteristics of the people living here changed. In a relatively short period of time, the affiliation of Transylvania to the two countries changed; this lead to changes in legislation and governing policies. In the current case what is of importance is the change of the national language: when Transylvania belonged to Hungary, the national language was Hungarian, when the region belonged to Romania, the national language was Romanian. As a consequence to this governing change, the people of Transylvania developed a highly bilingual linguistic behavior. Currently, Transylvania belongs to Romania and the national language is Romanian. The history of the region influenced the development of bilingual families, who due to mixed minorities used both Romanian and Hungarian languages. The development of these bilingual families took place in a rather natural manner, setting a road for natural bilingualism to emerge. Speakers that originate from such naturally bilingual families usually have the ability to code switch between their native languages. Both languages enjoy the same level of prestige. Due to their native bilingualism, such speakers have the ability to use both languages fluently in formal and informal settings. Other types of bilingualism emerged also. If the prestige of the languages is taken into consideration, two types of speakers are to be discussed. There are speakers that refuse to speak the Romanian language because they consider it to have lower prestige than the Hungarian language they use. This type of attitude is also an attempt to conserve national identity and traditions through the language they speak. It is important to mention that this identity is motivated historically. It should be made clear that there are those speakers that refuse to speak Romanian due to the lower prestige they associate to the language but still, they have competence in using Romanian; and there are those speakers that even refuse to learn the language or have any contact with it, thus not having any competence at all in the Romanian language. These types of speakers are not bilinguals due to refusal, but because they are not isolated from the world and because social requirements are driving more and more speakers in urban settings, their children encounter difficulties. The national language being Romanian, these ‘children’ must acquire competence in the language at a relatively late age for language acquisition. For these speakers, the Romanian language is truly a foreign language that they must learn. Due to isolation and limited contact, such speakers must become bilinguals as a social requirement. Examples of such cases are students that move in urban areas for the purpose of higher education. Some maintain the idea of language prestige, thus creating an attitude towards the Romanian language; others make great efforts in acquiring competences in the use of Romanian. Some might say that formal education needs to cover these issues, but the case was up until recently that the Romanian language was taught in such linguistically isolated areas, as described above, as a native language. Only recently a legislative project was put together that suggested that the Romanian language should be taught as a foreign language to such speakers. Even though the attempt is a step towards evolution of our civilized society, there is still the case of an entire generation that uses currently the Romanian language with great efforts. Code mixing and code switching In such cases of effort phenomena like code mixing can appear. Code switching requires a somewhat proficiency and fluency in both languages. Code switching enjoys a great deal of attention from sociolinguists. As opposed to code mixing, code switching has been agreed upon as being a real linguistic phenomenon. In what regards code mixing some might discuss its existence. Also, there has been linguistic work that considers the use of the terms code switching and code mixing as synonymous. In what follows, these theories, opinions will be discussed. It is obvious that the phenomena of code switching, respectively, code mixing occurs due to language contact. In the case discussed in the present paper, the Transylvanian RomanianHungarian language varieties spoken are of issue. As stated before, the catalyzing factors evolve around historical and social areas. This particular phenomenon is highly governed by geographical constraints. In other words, code mixing and code switching require a certain historical/social solidarity. Language contact implies the fact that two or more languages influence each other due to social, political or historic changes. The languages in question can be different dialects of one language that later evolve into distinct languages due to intelligibility. Thus, these contacts can take place between different languages, different varieties of languages or between varieties and languages. According to Hock (1991) the natural languages will always be in some sort of contact with each other based on different constraints: “There is always at least some contact with other languages or dialects” (1991:380). These contacts can be manifested on a lexical level in the form of the following phenomena: lexical borrowing, dialect borrowing, and foreign borrowing. In what follows these phenomena can be associated with the concept of code mixing. Lexical borrowing is defined as “(…) the adoption of individual words or even of large sets of vocabulary items from another language or dialect” (Hock, 1991: 380). Hock’s definition captures the fact that borrowings could be performed between different languages and he also introduces the idea of borrowings from different dialects. It must be mentioned that he makes a description of dialects as being “varieties of speech which are relatively similar to each other, whose divergences are relatively minor” (1991: 381). Language is described as being an “ensemble of such dialects- whether they are standard or vernacular, urban or rural, regional or supra-regional.”(1991: 381). Different languages are being defined as varieties that “differ from each other more noticeably, whose divergences are minor.”(1991: 381). Based on these categorizations and the cultural information available to each inhabitant of Transylvania, a distinction can be made between the Transylvanian variety of the Romanian language, the so called “Ardelenesc” variety and the standard institutionalized one, which is the national language. Even though intelligibility cannot be stated as being impossible, there are differences in the basic lexicon and accent which are to be accounted for as the result of contact with the Hungarian language. In the other pole of linguistic contact there is the case of the Hungarian language spoken in Transylvania, which is greatly different from the Hungarian language spoken in Hungary. First of all of great importance is the contact with the Romanian language which influenced the basic lexicon and the accent of the variety. Some speakers that migrate to Hungary might say that the Transylvanian variety of the language has developed to an extent that is has become unintelligible with the language in Hungary, which at its own turn was in contact historically with neighboring languages like German. With these perspectives in mind one could state the fact that the Transylvanian variety of the institutionalized Hungarian language has started developing into a language on its own. The variety of the Romanian language on the other hand remains greatly intelligible with the institutionalized variety of the Romanian language. It could be the case that the existence of the phenomena of linguistic contact, namely code switching and code mixing can prove to be a landmark in the development of the Transylvanian variety of the Hungarian language as a language on its own. For now, this remains only a speculation of a fictional scenario, only the passing of time will confirm or infirm this statement. As for now, the following generalizations can be made in what concerns the linguistic type of the two varieties. These generalizations use Sapir’s (Croft, 1990: 40-41) classification of languages based on the number of morphemes, degree of alteration of morphemes and types of dominant concepts. The Transylvanian variety of the Hungarian language could be accounted for as being synthetic (small number of morphemes per word), agglutinative (simple affixation as the degree of alteration of morphemes), and of the Type I and IV (concrete and pure relational concepts). The Transylvanian variety of the Romanian language on the other hand could be polysynthetic (large number of morphemes per word), fusional and symbolic (considerable morphophonemic alteration and suppletion) and is of Type I and IV (concrete and pure relational concepts). The above generalizations should be taken with a pinch of salt because they are highly intuitive and due to considerable lack of research on the typology of the two varieties, there is a possibility for error. Such generalizations should require a larger amount of research data than the ones existing, but nevertheless, these generalizations can prove to be a starting point for further typological research. It could be the case that due to the fact that the two languages share the same type I and IV concepts, code mixing and code switching are possible. Also, Hock refers to borrowing as being an ‘adoption’ process which will be detailed further on as having different stages. Another definition of borrowing that focuses on language contact: “The borrowing of words is the most common type of structural change that results when people speaking different languages are in contact and some of them become bilingual” (Scotton, 2006: 231). This defines borrowing by means of structural change. This term is not made clear by the author, but it can be accounted for as a change that has to do with a grammatical perspective on languages. Also, the idea must be noted that borrowings are to be one of the causes for bilingualism. An attempt is made from the author to make a connection between structural change and bilingualism. Further on, she does not make a difference between borrowing lexical, grammatical structures as whole and incorporating them into speech and between borrowing words or concepts which by some means which will be later on discussed have been integrated into the receiving language. A suggestion could be made at this point, namely that based on this difference in borrowing, the term code switching could be associated with that of borrowing lexical and grammatical structures without altering them and the term code mixing could be associated with borrowing lexical structures or concepts and altering them. Thus, in the case of linguistic contact the manifestation of borrowings can be accounted for as code switching and code mixing, the difference between the two terms being the degree of integration that ranges from integrating lexical structures without altering them to integrating lexical structures, concepts by different means. Thus, there can be made a difference between ‘unmodified adoption’ and adaptation. This difference was surprised by Hock in the following statement: “In the various nativization processes one can recognize two recurrent routines. One of these consists in the unmodified adoption of foreign words and their morphology and/or phonology. In such cases nativization results only slowly and most grudgingly. The other approach, with different sub-routines, can be more properly called nativization, in that it attempts to integrate borrowed words, their morphology, and their phonology into the structure of the borrowing language: adaptation.”(1991: 408). As a final observation it could be stated that the implication of the terms ‘linguistic contact’ include the manifestation of the terms code switching and code mixing, and the implication of the terms code switching includes the manifestation of the terms lexical borrowing, the implication of the term code mixing includes the implication of the terms lexical borrowing which in its turn includes the processes of nativization. In what follows the processes of nativization the following differentiations can be made: phonological nativization and lexical nativization. Phonological nativization accounts for this process with the following statement made by Hock (1991: 390): “in order to be usable in the borrowing language, loans must first and foremost be ‘pronounceable’ “. This denotes the fact that due to different sound systems borrowings must succumb to a phonological nativization change which will allow the speakers of the borrowing language to use the borrowings with ease. An example of the sort is the name of the famous Transylvanian drink which in Romanian is named ‘pălincă’ and in Hungarian ‘pálinka’. These examples are not taken from the institutionalized variety of the two languages. They are taken from the varieties spoken in Transylvania. The term in the phonology of the Romanian language succumbs to the specific Romanian sounds, more specifically ‘ă’. In the Hungarian phonological system it denotes specific Hungarian sounds like ‘á’. As a consequence at a first glance it can be observed that one of the terms has been borrowed. As to which language is the donor language and which one is the borrowing language a broader discussion needs to be started which requires diachronic evidence on the phenomena. Synchronically, the existence of these terms cannot be accounted for. In this example it is obvious that phonological nativization took place through spelling. Also, an observation needs to be made of the fact that the number of syllables in the two terms is the same. This observation would be in concordance with Hock’s following statement: “(…) many languages nativize foreign borrowings such that they conform to native restrictions on word or syllable structure” (1991: 394). Another example is phonetical nativization is the borrowing from English to Hungarian of the word ‘quiz’. This term is spelled in the following manner ‘kviz’. This borrowing exists in the institutionalized variety of the Hungarian language. Another borrowing from the area of computer science is the English term ‘mouse’ which is nativized with the following spelling: ‘mauz’. Interestingly, Romanian borrowings from English have a tendency to maintain the spelling and pronunciation of the term in the donor language: mouse, management, leasing, computer, etc. Lexical nativization is a process which implies changes in the lexicon of a language. The following processes can engage in lexical nativization: loan shifts, calques. Loan shifts are defined by Hock (1991: 397) with the following definition: “These arise from a shift in meaning of an established native word, so as to accommodate the meaning of a foreign word. (…) That is, a foreign concept is borrowed without its corresponding linguistic form and without the introduction of a new word into the borrowing language”. Calque is defined by Hock (1991: 399) as: “This process consists in translating morphologically complex foreign expressions by means of novel combinations of native elements which match the meanings and structure of the foreign expressions and their component parts.” An example is the term borrowed from English ‘skyscraper’. In Romanian the term was calqued as ‘zgârie-nori’ – ‘cloud scratcher’; in Hungarian it was calqued as ‘felhőkarcoló’ – ‘cloud scraper’. These processes will further on be useful in differentiating code mixing from code switching. According to Hock (1991:408) there are several motivations for borrowings: need and prestige. Scotton (2006: 210) also agrees on prestige as being a motivation for lexical borrowing, but she defines prestige as “there is something more ‘attractive’ about that language”. There is another motivation given by Scotton: “innately based language universals push speakers in certain directions”. She motivates this statement by claiming that in most languages nouns are the ones that are being borrowed, and thus, this denotes a common ‘universal basis’ for languages. Even though this could very much be the case, it implies the fact that languages borrow from each other based on a universal basis, whereas the existence of such universals would imply the fact that every natural language has them in common. From this perspective Scotton’s motivation is somewhat invalid, from another perspective it could be the case that borrowings themselves are universal processes which every natural language uses to enrich their vocabulary according to social, industrial needs. Thus, what is to be regarded as a certain motivation for borrowing is the need for it. Prestige, on the other hand is somewhat of a different type of motivation, because it implies a unified opinion of speakers on what regards the status of a language. It is a sociolinguistic feature, whereas need does not imply a subjective involvement of speakers, but an objective linguistic, social need. Hock makes a difference between the two phenomena: code switching and code mixing. According to him, code switching is a response of language contact: “One common response, found especially in persons who are fluently bilingual, consists in switching back and forth between the coexisting languages, such that portions of a given sentence or utterance are in one language, other parts in another language.” (1991: 479). Hock also details the fact that code switching tends to be limited by syntax and morphology, and it will take place at ‘major syntactic boundaries’. This assertion implies the fact that code switching is highly dependent on phrase structure and word order. This would explain why often Hungarian language natives fail to use proper word order when using the Romanian language. The Romanian language has a Noun Adjective order, while the Hungarian language has an Adjective Noun order. Thus, the order of the terms in Romanian will succumb to the word order from Hungarian. This would explain why terms like the following do not seem to be ‘natural’ even though they are grammatical: ‘roşu (adj.) gard(n.), muraţi (adj.) castraveţi (n.), negru (adj.) gard (n.). etc. This phenomenon was believed to be a wrong instinctual use of language, but as the above explanation shows, it has to do with the use of word order. As a consequence, it can be stated that word order will highly influence speaker’s fluency and grammaticality. Compared to the definitions given above, Hock restricts code switching to bilingualism and fluency. Although, by no means is possible an objective measurement system for grading fluency, usually and practically intelligibility and correct grammaticality has been used to determine whether a person is fluent in a language. It would be somewhat safer to say that for sure, code switching will emerge in specific social contexts in native bilinguals. Thus, bilingualism would certainly be a sociolinguistic requirement for the manifestation of code switching. Scotton (2006: 234) defines code switching in the following manner: “The elements that make a clause bilingual may be actual surface level words from two languages. This is called codeswitching.” If the above given definitions are taken into consideration on what code switching is, then what actually defines Scotton is not code switching, it is code mixing. In what follows she associates the phenomenon of convergence with bilingual speech which has two languages as the underlying structure of a clause. In other words, one language provides abstract rules and not actual words. To shed some light on the phenomenon Hock gives the following definition for convergence: “the increasing agreement of languages not only in terms of vocabulary, but especially in regard to features of their overall structure.” (1991: 492). These definitions give the necessary amount of information to be able to differentiate convergence from other phenomena. In the case of code mixing the following definition is given by Hock (1991: 480): “while code switching takes place on a syntactic level, code mixing appears to be a lexical phenomenon. (…) Code mixing consists of the insertion of ‘content words’ from one language into the grammatical structure of another.” Scotton gives the Matrix Language Frame as a means to analyze the phenomenon. This method of analysis consists of identifying one of the languages present in bilingual speech as being the Matrix language which builds the frame of the speech, while the other language is the Embedded Language - the other participating language (Scotton, 2006: 243). This identification is based on separating the morphemes present in bilingual speech into two distinct categories: content morphemes and system morphemes. Scotton defines content morphemes by the following: “Content morphemes are those that either assign or receive theta roles. (…) They are basically semantic roles. But they are semantic in the sense that they refer to such relations within the sentence as whether a noun is an Agent or a Patient of the verb.” (2006: 245) She provides the following example: the verb ‘give’ subcategorizes for three thematic roles, an Agent, a Patient, a Beneficiary. Discourse markers are also considered content morphemes at “the discourse level”. Scotton motivates this claim with the idea that discourse markers like ‘therefore’, ‘so’, ‘but’, limit the constitution of what follows after them. She refers to this aspect as discourse level thematic roles. System morphemes do not assign or receive thematic roles. According to Scotton system morphemes are all affixes and some functional words (e.g. determiners and clitics). This analysis method can be used only in the case of bilingual speech where the two languages do not participate equally in the production of speech, thus one of the languages supplies the morphosyntactic frame. The other language is identified as the Embedded Language. Thus content morphemes can be identified as the elements of the Matrix Language, the system morphemes can be identified as the elements of the Embedded Language. Also, Scotton gives the following principle to sustain the difference between the two types of languages: “In mixed constituents of at least one Embedded Language word and any number of Matrix Language morphemes, surface word (and morpheme) word order will be that of the Matrix Language.” (2006: 244). Thus word order could also be explained by the identification of the Matrix Language, respectively that of the Embedded Language. An extension of the Matrix Language Frame analysis model is the 4-M model which does not change anything to the MLF model but continues it in making a categorization into four different types of morphemes. System morphemes are splitted into three types. The morphemes categorized in this model are defined as conceptually activated. This means that a speaker’s pre-linguistic intentions activate them. This level is called the mental lexicon level. This level consists of elements called ‘lemma’ which is the name for the abstract elements that underlie actual surface-level morphemes. These lemmas contain necessary information to produce surface level forms. These are called early system morphemes because their early activation in the language production process e.g. plural markings, the definite article ‘the’, the indefinite article ‘a’,’an’. Late system morphemes are activated at a later production level. At this level there is the formulator which receives directions from lemmas in the mental lexicon. These are bridge system morphemes, which occur between phrases that make up a larger constituent, e.g. the possessive noun and the element that is possessed. Outsider system morphemes: the presence and form of an outsider depends on information that is outside the element with which it occurs. These outsider morphemes must come from the Matrix Language (Scotton, 2006: 267). It must be noted that Scotton does not make a difference between the use of the terms code switching and code mixing. Moreover, she does not use the term code mixing at all. If the definition given above by Hock in what regards code switching and code mixing is concerned, what Scotton refers to as code switching is in fact code mixing, thus the Language Matrix Frame being a suitable tool for the analysis of code mixing and not code switching. Case study In what follows, proper cases of Romanian-Hungarian code switching and code mixing will be analyzed. The recordings were made in Transylvania in the county of Harghita. The population of this county is highly bilingual, thus frequent examples of language contact can be noted. The participants in the conversations are natural bilinguals of Romanian and Hungarian language. Some have acquired bilingualism due to marriage, thus, these mixed families prove to be a suitable and productive setting for native bilingualism of the children growing up in such bilingual settings. Usually the language acquiring mechanism is done in an informal setting, but it is also encouraged by formal education. The following section will focus in applying the above discussed issues to ‘real’ life conversations. The examples given are clips from dialogues taking place in an informal setting. The participants shared close relations with each other. The clippings were selected according to the encounter of code switching and code mixing phenomenon. The conversations were transcribed and the peculiarities of the oral discourse were not maintained because in this case they are not relevant. A spelling was used which is common to transcriptions, thus, there are no diacritics or punctuation marks. The participants are kept in anonymity, thus their contribution is noted with a capital letter. Words belonging to one language or the other are marked in brackets: (ro.), (hu.). Also, longer periods of mixed language are noted with [ro.], respectively [hu.].The type of morpheme will be mentioned below each word. Content morphemes will be noted with the abbreviation cont., system morphemes with the abbreviation syst. Clip 1: B: <ma L.> ma orsisi une [ro.] you(interj.) L you(interj.) any dapoi asta-i asta-i coptsila meri where go-2SG coptsila asta child(girl) this asa lucra well this-3SGf. is this-3SGf. is child(girl) like(comp. adj.) worked ca un baiet meg vele a kerteltem en like a boy [hu.]and with2SG the fenc(vb.)1SG I vele with2SG This part of the clip is spoken in the Romanian language. The speaker gives a quote of someone who spoke of her in Romanian. To note the fact that Romanian word order is used, the noun, adjective, pronoun accords are expressed by inflections and they are used grammatically. Main word order would appear to be VSO. Up to this point, there isn’t any mixture of the two languages. From this point on, the speaker starts using the Hungarian language. A probable reason for this is the fact that the narrator begins introducing personal opinion and her own memories on the facts. At this point it is safe to say that the speaker’s native language is Hungarian and that when faced with a familial informal setting this language will be used. hegyre vele kaszalni vele takarni vele mountain(on) with2SG cut grass with2SG make hay with2SG szenaert vele mindenfelit after hay with2SG everything mindenfelit na aztan azutan votak keresztanyamtol everything well then godmother-(from)pos.1SG megvette edesapam bought-3SG sweetfather-1SGpos. the after were3PL a tehent egy tehent s cow cow a and akkor a tehen megbornyuzott s az ket evre then cow and that two years(past) the gave birth3SG lett egy jo tino belole s akkor become(future) a good cow(masc.) from-3SG and then minja volt marhank soon(fast) was cow-1PLpos. aaa gestant vett szerelt akkor edesapam then ize::: jarhas sweetfather-1SGpos. bought marhank s cow-1PLpos. and managed to get szekeret meg ize csinalta fata lu maria cart and aaa made(it) (ro.)girl of-3SGpos.m. maria The speaker continues to narrate using the Hungarian language. Word order employed is that of the Hungarian language: NG, AN, also the main word order is that of SVO. By the end of the clip the speaker uses a sequence of words in Romanian to refer to a Romanian person. This is in concordance with the above observations; the speaker uses Hungarian to refer to close family relations and happenings and uses Romanian to refer to happenings outside the family circle. Thus a conclusion can be drawn, that is, in family circles the Hungarian language was used when growing up and later in life. This is the reason why memories of close family relations, adventures will be related in Hungarian. It also must be noted that the interlocutor of the speaker knew both the Hungarian and the Romanian language. At this point, based on this example, a few generalizations can be made on what concerns the phenomena of code switching. This Clip is surely a manifestation of code switching because it is a bilingual speech, where grammatically speaking elements from both languages appear with different purposes in mind. The section in Romanian is not simply the use of the language grammatically or a choice made because of a lack of alternatives. This section engraves an attitude that the speaker has towards past happenings. Based on these observations, code switching can prove to be a useful tool to create the profile of the speaker. Code switching also requires fluency in both languages, fluency that for the sake of simplification will be reduced to grammaticality and intelligibility. Clip 2 B: pocsoja volt mlastina ott aje a fel kellett water pond was (ro.)swamp there (…) the up must-past ajjal protapra a szekerre elol ide s cart-on in front here and a stand the a (ro.)wood-on the ugy hajcsad a like go(order)2SG the izere something-on the marhakot me nem tudtal menni cow-PL because not can go Clip 2 is a narration spoken mostly in Hungarian. It only has two mixtures of words from Romanian. The speaker uses these probably for a lack of term in the Hungarian language. This could be considered a case of code mixing because the words from Romanian are mixed into the Hungarian grammatical structures. To note that these are nouns inserted after verbs. They act like objects, thus the word order SVO is employed. The second term ‘protap’ is given a location suffix, which integrates the word into the grammatical structure of the sentence, thus the preposition from Romanian is dropped ‘pe’. There is an attempt to level the mix with the use of the term ‘izere’ which is term referring to general things. The first inserted term is not altered in any way; it acts as a description term for the setting. The use of this term and not another could be motivated by native language use. Thus, the term ‘mlastina’ was internalized after the ability to construct an internal grammar of the native language. It should be safe to say that this Clip is an example of code mixing. If this is the case the Language Matrix Frame analysis should be possible. As a consequence, to the analysis, content morphemes and the system morphemes originate from the Hungarian language. Thus it is safe to say that the Matrix language is the Hungarian language and the Embedded Language is the Romanian language. Even though the contact is limited, it is somewhat obvious that this should be the case. Conclusions and further discussion This paper was an attempt to define code mixing and code switching. The idea arouse because there isn’t a univocal definition of these two phenomena that are obviously different from each other. With the help of bilingualism, code switching was defined as the shift of grammatical structures or sentences without their alteration. Code mixing was defined as a mixture of grammatical elements of two languages. These phenomena are not institutionalized and they usually take place in a small number of cases. In this case it could be stated that the phenomena appeared due to social, historical, political changes, which lead mixed families to assign the Hungarian and the Romanian language equal prestige. Another important issue is the sociolinguistic considerations. As stated above, the phenomena can prove to be an important resource for creating the linguistic behavior profile of a bilingual speaker. As a closing conclusion, it is possible that code mixing and code switching are used by speakers to maintain and create their social, national identity. It can also prove to be a means to maintain traditions specific to each nation. As further discussion, it is important to state that speakers need to have the freedom to speak and learn the language they desire. It is also important to understand that speakers who have a single language as their native language will be influenced future on in acquiring a second language by their native one. Thus, second language learning needs to be done in regards to the native language and with the idea in mind that the second language due to more limited contact will remain a foreign language. This influence is clearly visible in the case of code mixing, and the dominating language which embeds the second language. The phenomenon of code switching and code mixing is a truly interesting one, proving once again that the human mind is capable of amazing performances. References Croft, W. (1990) Typology and Universals. The Bath Press, Avon. Hock, H (1991) Principles of Historical Linguistics. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin. Myers-Scotton, C (2006) Multiple Voices. An Introduction to Bilingualism. Blackwell Publishing, Cornwall. Marton Eva-Carmen PHD student University “Babes-Bolyai”, Faculty of Letters Cluj-Napoca, 2012