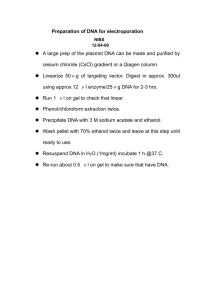

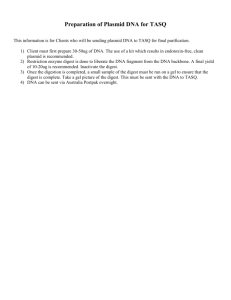

Lab Manual - DNA Section

advertisement