ESTONIA - European Society for Translation Studies

advertisement

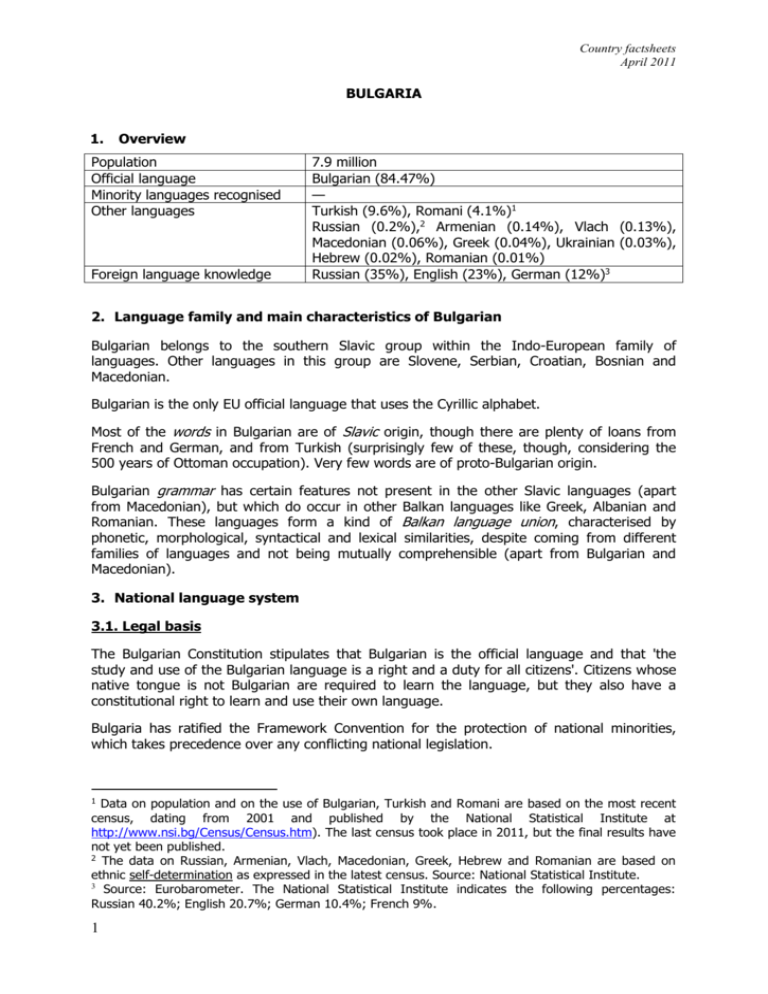

Country factsheets April 2011 BULGARIA 1. Overview Population Official language Minority languages recognised Other languages Foreign language knowledge 7.9 million Bulgarian (84.47%) — Turkish (9.6%), Romani (4.1%)1 Russian (0.2%),2 Armenian (0.14%), Vlach (0.13%), Macedonian (0.06%), Greek (0.04%), Ukrainian (0.03%), Hebrew (0.02%), Romanian (0.01%) Russian (35%), English (23%), German (12%)3 2. Language family and main characteristics of Bulgarian Bulgarian belongs to the southern Slavic group within the Indo-European family of languages. Other languages in this group are Slovene, Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian and Macedonian. Bulgarian is the only EU official language that uses the Cyrillic alphabet. Most of the words in Bulgarian are of Slavic origin, though there are plenty of loans from French and German, and from Turkish (surprisingly few of these, though, considering the 500 years of Ottoman occupation). Very few words are of proto-Bulgarian origin. Bulgarian grammar has certain features not present in the other Slavic languages (apart from Macedonian), but which do occur in other Balkan languages like Greek, Albanian and Romanian. These languages form a kind of Balkan language union, characterised by phonetic, morphological, syntactical and lexical similarities, despite coming from different families of languages and not being mutually comprehensible (apart from Bulgarian and Macedonian). 3. National language system 3.1. Legal basis The Bulgarian Constitution stipulates that Bulgarian is the official language and that 'the study and use of the Bulgarian language is a right and a duty for all citizens'. Citizens whose native tongue is not Bulgarian are required to learn the language, but they also have a constitutional right to learn and use their own language. Bulgaria has ratified the Framework Convention for the protection of national minorities, which takes precedence over any conflicting national legislation. Data on population and on the use of Bulgarian, Turkish and Romani are based on the most recent census, dating from 2001 and published by the National Statistical Institute at http://www.nsi.bg/Census/Census.htm). The last census took place in 2011, but the final results have not yet been published. 2 The data on Russian, Armenian, Vlach, Macedonian, Greek, Hebrew and Romanian are based on ethnic self-determination as expressed in the latest census. Source: National Statistical Institute. 3 Source: Eurobarometer. The National Statistical Institute indicates the following percentages: Russian 40.2%; English 20.7%; German 10.4%; French 9%. 1 1 Country factsheets April 2011 The Law on discrimination, which entered into force on 1 January 2004, requires state institutions, public bodies and local government to work towards the balanced participation in government and decision-making bodies of men and women, and members of ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities. 3.2. Languages in the public administration and in the judiciary The judiciary act stipulates that Bulgarian is the language of the judiciary. Where one of the parties does not know sufficient Bulgarian, the court can appoint an interpreter at its expense. Records of proceedings are drafted in Bulgarian, but foreign words/expressions may be used where they have special significance. Bulgarian is the language of public administration. With very few exceptions, the official websites of ministries are in Bulgarian and English. The former Minister for Public Administration, Mr Nikolay Vasilev (2005-2009), encouraged local government entities to have an English version of their website. 3.3. Education and training 3.3.1. Education and training in official and regional languages Bulgarian is the official language in nursery and all other schools (day or boarding). Teachers are required to communicate with the children in Bulgarian, apart from in foreign language classes, native-tongue courses or the like. Children who do not speak mother-tongue Bulgarian must learn Bulgarian, but are also entitled, in state schools and under the control and protection of the state,4 to attend courses in their mother tongue as an optional subject. There are no minority-language universities in Bulgaria. 3.3.2. Language learning Children start learning their first foreign language in the second school year (at the age of eight — it is a compulsory subject). In the 2006/2007 school year, the most widespread first foreign languages were English (647 651 learners), Russian (200 087), German (164 364), French (76 129), Spanish (19 166), Italian (6 203) and others (4 282), including Greek, Turkish, Romanian, Japanese, Chinese, Arabic and Portuguese. A second foreign language kicks in in the eighth year (age 14). Eurostat reports that in 2007 76.9% of children in the second cycle of secondary education in Bulgaria were learning two foreign languages. Bulgaria has a strong tradition of teaching foreign languages intensively. For the past fifty years there have been language grammar schools, or bilingual grammar schools, specialising in teaching two foreign languages, and where some of the subjects (e.g. history, geography, physics, biology) are taught in the first foreign language. Pupils are admitted at the end of the seventh year of schooling (at the age of 14) and start learning the two languages from 4 In the 2002/2003 school year, for example, Turkish was taken as an optional subject by 31 349 children in 420 schools, with 588 teachers. 2 Country factsheets April 2011 the very basics. These schools are highly prestigious and are often decried by the media and by ordinary people as 'elite schools'. Pupils' language skills are tested after the 8th grade. 3.3.3. Language education for immigrants In 1994 Bulgaria became a member of the International Organisation for Migration. In September 2009 the Bulgarian office of the organisation started setting up a network of information centres for immigrants, the first one opening its doors in Burgas on 18 September. The network is funded in part by the European Fund for the integration of thirdcountry nationals; one of its services is the provision of Bulgarian lessons for immigrants. 3.3.4. International schools The American University in Bulgaria opened its doors in the city of Blagoevgrad in 1991.5 The city of Botevgrad hosts an International Business School6 offering bachelor's and master's programmes in Bulgarian and English, and awarding Bulgarian and Dutch degrees. According to the official Ministry website, there are no foreign schools in the country. 3.4. Languages and the labour market In 2009, 47 532 civil servants (a little over half the total) knew a foreign language: 27.1% English, 22.3% Russian, 4.5% French and 3.9% German. In 2006, the Ministry of Public Administration and Administrative Reform organised for the first time a centralised recruitment database of applicants for jobs in the civil service (akin to an EPSO competition). It comprised two parts: the first compulsory and the second specialised and optional. Language testing (English, French, German) was in the second part, which meant that knowledge of a foreign language was not a condition for entry. It is, though, regarded as a point in the candidate's favour. In the private sector, knowledge of English is one of the most sought-after skills. 3.5. Use of languages in the media Turkish programmes on state radio: Radio Bulgaria broadcasts in Turkish each day from 08:00 to 09:00, from 13:00 to 14:00 and from 20:00 to 21:00 in regions with a sizeable Turkish-speaking population. Turkish programmes on state TV (BNT): There is a news programme in Turkish each working day from 16:10 to 16:20. There are newspapers in Turkish, Russian, Armenian and Macedonian, albeit with no great print-run. Newspapers for Roma are in Bulgarian. 'Aurea' is a regional radio station for Roma, broadcast in Bulgarian. The digital programme has national coverage. Most of the music is specific to Roma, or Turkish-speaking Roma, or is Indian. 5 6 3 http://www.aubg.bg/ http://www.ibsedu.com/?lang=en Country factsheets April 2011 3.6. Language institutions The Institute for Bulgarian Language,7 part of the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, is the main centre for research and normative studies. It focuses on the current status of Bulgarian, its history, the range of dialects and the way it interacts with other languages. The Institute coordinates and decides on national language policy, maintaining links with Bulgarian university departments abroad and with other associated institutions. Today, 67 years after it was founded, it boasts twelve research entities, comprising eleven departments and an information centre / library. The Translation and revision centre8 was set up in 2001 to translate the EU acquis with a view to Bulgaria’s projected membership of the European Union. It was disbanded in November 2009, but its translation work formed the basis of a public-access multilingual database, with terms, keywords and expressions in Bulgarian, English, French and German. 4. Language industry The European Commission’s 2009 study on the size of the language industry failed to come up with any estimate of the volume and turnover of the market in Bulgaria. There are a wide range of translation agencies and a number of translators’ associations, e.g. the Association of Translators and Interpreters in Bulgaria,9 the Union of Translators in Bulgaria,10 and the Bulgarian Association of Professional Interpretation and Translation Agencies,11 which is a member of the European Union of Associations of Translation Companies. 5. Language status in international organisations As of 1 January 2007, Bulgarian is one of the 23 official languages of the European Union, and the Cyrillic alphabet is one of the three official alphabets of the EU. 6. Sensitive language issues 6.1. Context Bulgarian belongs to the southern Slavic group within the Indo-European family of languages. In the ninth century, the Bulgars were the first to use the Cyrillic alphabet which, in its present Bulgarian version, has 30 letters. Cyrillic derives from the Greek alphabet, with additional characters to represent Slavic sounds with no Greek equivalent. Bulgaria was the cultural core of the mediaeval Slavs, and from it the Cyrillic alphabet spread to Serbia, Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. The alphabet is now used in six Slav countries: the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Bulgaria, Belarus, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine, and in a number of Asian countries: Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Mongolia. 7 http://www.ibl.bas.bg/en/index.htm http://www.trc.government.bg/en/terms 9 http://www.translators-bg.com/index.php?lang=en&page=home 10 http://www.bgtranslators.org/ 11 http://www.bapita.eu/ 8 4 Country factsheets April 2011 Old Slavic (also known as Ecclesiastical Slavic) is the oldest documented Slavic language and is the predecessor of modern Bulgarian. 6.2. Current situation 6.2.1. Macedonian Before the codification of the Macedonian language in 1945, some linguists regarded it as a dialect of Bulgarian. Even today there are dialectology handbooks in Bulgaria containing maps of Bulgarian dialect usage that cover the whole of the FYROM. In the early years following the declaration of independence in 1991,12 Bulgarian television did not translate what Macedonian speakers were saying. More recently this tendency has disappeared and, as a mark of respect for Macedonian, the Bulgarian media now interpret from Macedonian into Bulgarian. Nonetheless, Macedonians frequently take part in Bulgarian TV programmes without an interpreter. Generally speaking, the Bulgarian authorities do not comment on anything to do with the Macedonian language. In one interview, though, on 1 October 2008, the current President of Bulgaria said, on a question to do with the recognition of Macedonian: “...We have recognised the Republic of Macedonia under international law, but no-one is demanding the recognition of a language. I think we all know how and why the language was created...”13 There is a Macedonian organisation going by the name OMO Ilinden — Pirin. It was set up in 1999 to defend the rights of the ‘Macedonian minority’ in Bulgaria. It stood in the local elections in 1999 and got a mere 3000 votes in the Blagoevgrad region (aka unofficially Pirin Macedonia). In 2000 the Bulgarian Constitutional Court banned the organisation from taking part in political life because of its separatist tendencies. 6.2.2. A referendum on television news in Turkish In 1999 Bulgaria ratified the Framework Convention on the protection of national minorities. 2000 saw the start of a news programme in Turkish, broadcast every working day on the state TV channel BNT1. The nationalist party Ataka disapproved of the programme, and there is an online petition against it.14 In December 2009 Ataka called for a referendum to give people the chance to vote for or against a news programme in Turkish. On 15 December 2009 it was decided at a meeting15 between the Prime Minister, Mr Boyko Borisov, and the Ataka leader Mr Volen Siderov to hold the referendum, with the Prime Minister's party GERB (holding 116 seats in the 240-seat Parliament) supporting the organisation of a referendum. However, a few days later, on 19 December, and in response to reactions in the media and from the President, the Prime Minister went back on the idea and said that the time was not Bulgaria was the first country to recognise the independent Republic of Macedonia under its constitutional name. 13 http://www.president.bg/news.php?id=3163 14 http://bgpetition.com/novini-na-turski/view.html 15 One fifth of all MPs (=48) have to sign any request for a refendum. If Parliament agrees, within one month, the President has to issue a decree calling for the referendum to be held. 12 5 Country factsheets April 2011 ripe for a referendum, and that it would displease Europe. He also said that he hoped Parliament would take a reasonable stance. 6.2.3. The name of the euro in Bulgarian This was a highly controversial subject in 2007. Bulgaria insisted that the single currency be written in Bulgarian as "евро" [evro] (as in the name of the continent Европа [Evropa]), whereas the European Central Bank insisted on 'eypo' [euro]. The then Minister for State Administration, Mr Nikolay Vasilev, defended the Bulgarian position. On 18 October 2007 Bulgarian was authorised to call the European currency евро in Cyrillic in official documents.16 The question of whether Bulgaria will be allowed to use евро on banknotes once it is in the euro zone remains for the time being open. 7. DGT in Bulgaria DGT Field Office: DGT opened a Field Office in Sofia in August 2008. One person is currently employed there. European Master’s in Translation (EMT): The EMT is a project that encourages European Universities to establish a common curriculum for translator training. The EMT aims to: – encourage universities to develop post-graduate courses in translation and provide them with a model curriculum of a Master’s degree in translation; – develop the labour market for translators in the new Member States; – make DGT standards visible to the academic world across the European Union; – promote multilingualism by strengthening the Commission’s ties with universities involved in translation research and teaching, and train professional translators, enhancing standards where necessary. One Bulgarian university programme was selected for inclusion in the EMT network: the Магистърска програма: Превод. (Master's Programme: Translation) offered by the Faculty of Classical and Modern Philology of Sofia "Sv. Kliment Ohridski" University. Three other universities responded to the EMT call but failed to meet the admission criteria.17 Juvenes Translatores: This is a translation contest for pupils of EU schools launched by DGT in 2007 with the aim of disseminating understanding of the translation profession and familiarising students with European language policy. The fourth edition took place in November 2010, attracting a record number of entries: of 64 applicant schools, 18 were selected to take part. The Bulgarian winner, Boryana Andreeva Ivanova, from Foreign Language High School "Exarch Joseph I" (Lovech), translated a text from German into Bulgarian. 16 http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSL1868684020071018 The New Bulgarian University in Sofia, with its programme "MA in Translation and Interpreting", the University of Plovdiv "Paisii Hilendarski", with its programme "European Master's in Translation" , and the University "Konstantin Preslavsky" in Shumen, with its programme "Linguistics and Translation". The University of Veliko Tarnovo "St. Cyrille & St. Méthode", which offers Master’s in translating and interpreting, did not apply under the first EMTcall. 17 6 Country factsheets April 2011 Terminological cooperation: On the initiative of DGT's Bulgarian Language Department, a Bulgarian terminology network is now being set up, bringing together all the translation services in the European institutions, the Institute for Bulgarian Language, the Bulgarian Council of European Affairs and leading universities. It will provide a forum for systematic consultation, coordination, queries, training and quality control. The Sofia Field Office will be also involved in this. 7