Outline - Mississippi Department of Education

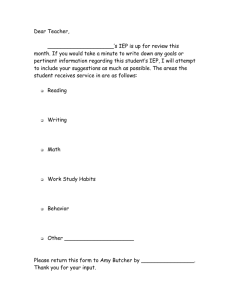

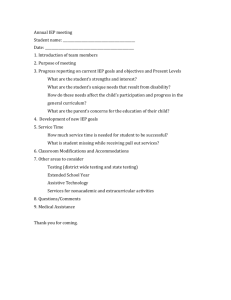

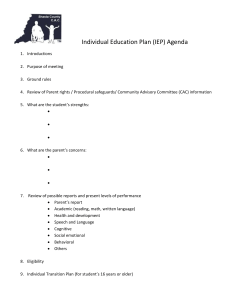

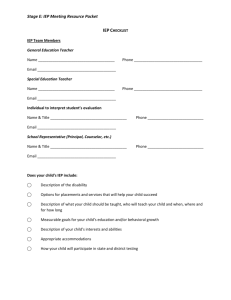

advertisement