MSP Kenya biomass energy - Global Environment Facility

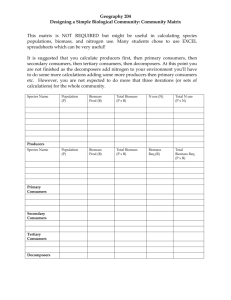

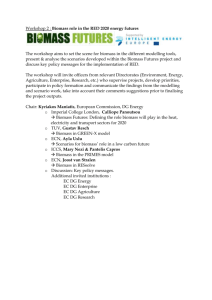

advertisement