FORMAZZJONI U INFORMAZZJONI MILL

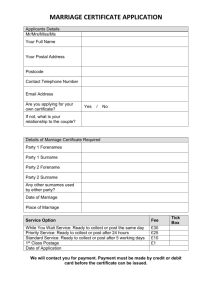

advertisement

FORMAZZJONI U INFORMAZZJONI MILL-KUMMISSJONI TEOLOĠIKA (3) 16 ta’ Marzu 2012 Wara l-materjal li ntbagħat fl-aħħar ġimgħat dwar il-pastorali mad-divorzjati li għaddew għal żwieġ ieħor, huwa f’waqtu li nifhmu pożizzjoni differenti – dik li ppropona Paul De Clerck, saċerdot Franċiż u professur tat-teoloġija pastorali u tal-liturġija fl-Institut Catholique ta’ Pariġi. Huwa importanti li nisimgħu qanpiena oħra, biex imbagħad nagħmlu l-konklużjonijiet tagħna. Paul De Clerck, “Reconciliation for divorced and remarried believers”, in Theology Digest 49 (2002) 217-225. The main points in the article: (a) De Clerck commences his article by referring to the practice in the Orthodox Church which allows a second (possibly a third) marriage “according to the economy” – a marriage which embraces a penitential dimension. With regard to remarried divorcees, the author reminds us that the teaching of the Catholic Church affirms the objective contradiction between divine law and the situation they have entered through a second marriage (p.217). (b) De Clerck then proceeds to mention three well-known solutions advocated by the Church to remarried divorcees: i. to investigate whether their first marriage is null through recourse to the ecclesiastical tribunals; ii. to discontinue the second relationship, although this has its problems because there can be obligations to children born from that relationship; iii. when the second union is maintained, the spouses are invited to live in continence because their sexual relationship is adulterous (p.218a-b). 1 (c) The author states that the canonical discipline of the Church rules out “any positive consideration of the second union” (p.218c) on account of the fact that the latter undermines the indissolubility of the first marriage. He holds that for remarried divorcees, their second union offers hope after the pain of a previous break-up, but this hope is tarnished because the Church considers the second union scandalous and sinful. He notes what, in his opinion, is the contradiction between invited remarried divorcees to the celebration of the Mass, insisting with them that they are not excommunicated, and then not permitting them to receive the Eucharist (p.218d). He also observes that different priests act differently – some admitted remarried divorcees to the sacraments, while others stick to Church law – saying that this lack of uniformity gives rise to injustices (p.219a). (d) De Clerck then contends that while the Church underlines the sinfulness of the life of remarried divorcees (this constituting an ongoing adulterous relationship), there are many other equally sinful situations (e.g. the production and the sale of armaments, unjust economic or political practices, the exploitation of the poor) where sacramental reconciliation is possible. He insists that all these cases, including an ongoing adulterous relationship in the case of remarried divorcees, are lasting and public in nature. Positively, he quotes Bishop Léonard who correctly insists that all in these long-term cases, the sinful situation must be remedied before reconciliation, which means that the Church is not distinguishing between two sets of serious sins (p.219b-c). (e) The personalist emphasis with regard to marriage is then treated (p.220a) by De Clerck. The intention of the spouses is “a lifetime of committed love and the permanence of the conjugal bond is still extremely important” (p.220a). Yet, there are cases when although the spouses’ intention was a lifelong marriage bond, their relationship experiences destruction. Durwell talks of an “indissoluble but destructible marriage” (p.220b). Other authors 2 talk of the “death of the first bond”, accompanied by a sense of anguish, failure and bitterness, and the multiple consequences from this situation. De Clerck voices the sentiments experienced by Christian believers in these situations. He states that while the personalist dimension remains central to the Christian theology of marriage, these individuals suffer because the Church continues to insist upon an essentialist concept of marriage and reiterates the permanence of their first bond, when they have re-experienced love and hope in a second union. Their intention is to overcome the failure of their first marriage, and, they say that instead the Church tells them to return to the “suffering and death” of their previous marriage (p.220c). De Clerck asks what, to him, is an important question: “In this situation the partners should be able to acknowledge their failure and perhaps the sin which is its origin, but could the Church not also integrate recognition of the failure of a marriage?” (p.220c) (f) De Clerck then proceeds to reflect upon the history of the sacrament of Penance. He refers to the reintegration of the lapsi into the Church after they repented of the serious sin of apostasy. He also talks of the ancient practice of “public” penance when for the very serious sins of apostasy, adultery and murder, individuals were not considered to be full members of the community any longer, and they were officially declared “penitents”, undergoing a somewhat lengthy period of public penance. Reconciliation took place when they were re-accepted by the bishop on Holy Thursday, in preparation for the celebration of Easter (p.221a). This whole process entailed a sense of spiritual pilgrimage, the embracing of a particular status (that of a penitent), and an emphasis on the connection between God’s mercy and ecclesial relationships (p.221b-c). (g) The author of the article raises a number of issues: i. a loss of the ecclesial sense of the sacrament of Penance and Reconciliation; ii. in the case of remarried divorcees, can one a priori rule out the existence of contrition?; iii. what about divorcees who have not remarried? Is their any 3 possibility of reconciliation with God and the Church if they are truly contrite for the failure of their marriage? (p.221d); iv. the issue regarding remarried divorcees should not be centred on whether or not they can receive the Eucharist, but on how the sacrament of Reconciliation should come into the picture (p.222a). (h) De Clerck affirms that a first step is to stop identifying “failure with fault or sin” (p.222a). He reminds that failure can be inculpable, and he gives the example of manslaughter (which is distinct from murder). Now, he argues, if a person’s physical death can, in certain cases, be inculpable, why is inculpability not applicable “for less violent acts”, such as the failure of marriage? (p.222b) (i) The Church is a community of pardoned sinners. At the very centre of the life and experience of the early community, the first believers acknowledged the reality of failure or infidelity to the Lord, but they were also cognizant of the fact that the Lord could “transform failure into life” (p.222c). Basing himself on the truly ecclesial nature of reconciliation, De Clerck then proceeds to propose the sacrament of Reconciliation to divorced and remarried believers. He affirms that this “proposal notes a serious failure in their personal existence in connection with a public and ecclesial commitment on the day of their marriage; this failure may in part be connected with sin” (p.223a). The author is insisting that the focus to be made is not on the subsequent second union, but rather on the failure of the first. He insists that the Church is to offer its sacramental healing to the believer who has fallen short of his/her original commitment (p.223b). De Clerck holds that for those whose marriage has failed, “their status would be that of Christians who are temporarily no longer in full communion with the Church and who should therefore no longer receive communion. Moving beyond this temporary situation would be done with Church support and would issue in the sacrament of Reconciliation, the sign of God’s mercy, which also reestablishes Christians in ecclesial 4 communion and thereby reopens eucharistic communion to them. The possible involvement in a second union should be evaluated beginning with their reconciled status and not exclusively with the breakup of the first marriage” (p.223c). De Clerck proposes pastoral diocesan support in the iter of this process (p.223d – p.224a). Discernment criteria are to be included, while bearing in mind the fostering of sincere conversion, children from the first union, the requirements of justice, the overcoming of resentments, etc. (p.224b-c). Basing himself on the practices of the ancient Church for “public penance”, De Clerck proposes a period when the divorced individual embraces the “penitent status” when he/she is not in full communion with the Church, followed by a sacramental act of reconciliation with the Church during Holy Week or on Holy Thursday, enabling him/her to receive the Eucharist on Easter Sunday (p.224c). He concludes: “After this process, those who wish to enter a second marriage should be able to celebrate it. For it would be illogical to admit them to the eucharist, the most important sacrament of all, and to exclude them from another sacrament” (p.224d). (j) Paul De Clerck insists that room should be made for the reality of failure in Christian life. He holds that those spouses who have failed in their marriage are invited to undergo a process of conversion with regard to that failure, and to be subsequently reconciled with the Christian community (p.225a). Reactions: The position taken by Paul De Clerck is at the other end of the theological spectrum from the clarifications made by the Holy See, as outlined in the previous Information sheets, and as detailed below. Although De Clerck’s intention is a pastorally inclusive one, the conclusions he reaches are, theologically defective and very subjective. The proposals he makes – if put 5 into practice – would create confusion in the minds of the faithful with regard to the indissolubility of the marriage bond. One is struck by the fact that the author rarely underlines reconciliation with God, as if only reconciliation with the Church were sufficient in true conversion. He makes a one-sided emphasis on healing, which though positive in itself, forgets that true contrition requires metanoia, literally a change in direction, from a sinful situation. Metanoia asks for a healing process of this situation, and not its ‘artificial’ cover-up, or pretending it does not exist any longer. God is true to his word, and asks of his disciples to live a life of fidelity to his word. Christians have always been called and are still being called to radicality. Although the effort made by De Clerck in offering pastoral solutions is to be appreciated in the way he presents his arguments and opinions, nonetheless his conclusions are defective as the indissolubility of marriage is undermined. With regard to the mention he makes of the Orthodox Church allowing a “second” marriage, he seems to be unaware that the Coptic Orthodox Church does not permit this often-cited practice. Pontifical Council for the Family, The Pastoral Care of the Divorced and Remarried. New Recommendations and Pastoral Guidelines, January 1997 = Catholic International 8/5 (May 1997), pp.214-6. (a) This document refers to Pope John Paul II’s address to the plenary assembly of the Pontifical Council for the Family: “Let these ġdivorcedħ men and women know that the Church loves them, that she is not far from them and suffers because of their situation. The divorced and 6 remarried are and remain her members, because they have received baptism and retain their Christian faith” (24.1.1997, n.2). (b) The Church does not limit herself to condemn errors, but – as we read in Familiaris Consortio 83 and 84 – she exhorts Christian communities to support those who are in difficult marital situations, in particular, “those who are suffering the hurtful consequences of divorce” (p.214d). (c) The Church seeks: (1) to urge the whole community to show solidarity to those of its members in such painful situations; (2) to show trust in God’s law and the teaching of the Church; (3) to promote the virtue of mercy which respects the truth of marriage; (4) to engender a spirit of hope; (5) to provide adequate formation to priests and lay ministers entrusted with the pastoral care of families; (6) to promote the value of Christian marriage and conjugal life through three objectives – fidelity, supporting families in difficulty, and through spiritual guidance; (7) to help the separated and the divorced who are alone to remain faithful to the duties of marriage; (8) to encourage liturgical prayer for those undergoing difficulties in marriage. (d) Special care is to be shown to the children of the separated and the divorced, especially in catechesis. (e) Ecclesiastical tribunals are to be seen more as part of the pastoral dimension of the Church. Pastoral assistance is to be provided to those who present their case before the tribunal. (f) The pastoral guidelines presented by the Pontifical Council include these challenging proposals: “invite the divorced involved in a new union to: recognize their irregular situation, which involves a state of sin, and ask God for the grace of true conversion; observe the elementary demands of justice towards their spouse in the sacrament and their children; become aware of their responsibilities in these unions; immediately begin to walk towards Christ – who alone can put an end to this situation: though a dialogue of faith with the new partner in order to advance together 7 towards the conversion required by baptism, and especially through prayer and participation in liturgical celebrations, while not forgetting however that, since they have divorced and remarried, they cannot receive the sacraments of Penance or the Eucharist” (p.215d). The Church is encouraged to “foster an adequate understanding of contrition and spiritual healing, which also implies forgiveness of others, reparation, and an effective commitment to serve one’s neighbour” (p.216). Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, On Communion for Divorced and Remarried Persons, 24.6.2000 = Bulletin tal-Arcidjocesi 105 (September 2000), pp.475-8. The Pontifical Council for Legislative Texts, in agreement with the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, sought to offer further clarification concerning remarried divorcees and the reception of the Eucharist. Difficulties arose with regard to the proper interpretation of canon 915. The following aspects are to be highlighted: (a) “In effect, the reception of the Body of Christ when one is publicly unworthy constitutes an objective harm to the ecclesial communion: it is a behaviour that affects the rights of the Church and of all the faithful to live in accord with the exigencies of that communion. In the concrete case of the admission to Holy Communion of faithful who are divorced and remarried, the scandal, understood as an action that prompts others towards wrongdoing, affects at the same time both the sacrament of the Eucharist and the indissolubility of marriage. That scandal exists even if such behaviour, unfortunately, no longer arouses surprise: in fact it is precisely with respect to the deformation of conscience that it becomes more necessary for Pastors to act, with as much patience as firmness, as 8 a protection to the sanctity of the sacraments and a defence of Christian morality, and for the correct formation of the faithful” (p.476). (b) The Declaration seeks to clarify the meaning of “the manifest character of the situation of grave habitual sin” in the context of remarried divorcees. The Declaration affirms that remarried divorcees “would not be considered to be within the situation of serious habitual sin when, not being able, for serious motives – such as, e.g. the upbringing of their children – to satisfy the obligation of separation, they assume the task of living in full continence, that is, abstaining from the acts proper to spouses, and who on the basis of that intention have received the sacrament of Penance. Given that the fact that these faithful are not living more uxorio is per se occult, while their condition as persons who are divorced and remarried is per se manifest, they will be able to receive Eucharistic Communion only remoto scandalo (p.477, n.2c). (c) N.3 of the Declaration concerns the instance of the public denial of Holy Communion. Pastoral prudence highly recommends one to avoid such a public denial. The spirit of canon 915 is to be explained by shepherds of souls to those concerned, “in such a way that they would be able to understand it or at least respect it” (p.477). It is only if after all the precautionary measures have been taken and these did not achieve the desired result, that the minister of Communion, with utmost charity must refrain from distributing the Eucharist to those who are publicly unworthy to receive it. Moreover, pastoral charity also demands that an opportune moment is to be sought by the minister “to explain the reasons that required the refusal” (p.477). +++++++ 9