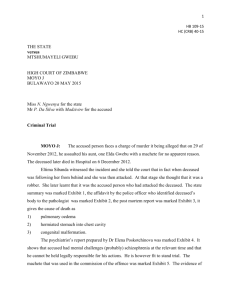

mcgill khan

advertisement