Short version - Microsoft Research

advertisement

Evolving Use of A System for Education at a Distance

Stephen A. White, Anoop Gupta, Jonathan Grudin, Harry Chesley, Greg Kimberly, Elizabeth Sanocki

Microsoft Research

Redmond, WA 98052, USA

{stevewh, anoop, jgrudin, harrych}@microsoft.com, greg@gak.com; a-elisan@microsoft.com

ABSTRACT

Networked computers increasingly support distributed, realtime audio and video presentations. Flatland is an

extensible system that provides instructors and students a

wide range of interaction capabilities [3]. We studied

Flatland use over multi-session training courses. Even with

prior coaching, participants required experience to

understand and exploit the features. Effective design and

use will require understanding the complex evolution of

personal and social conventions for these new technologies.

features. Social conventions develop slowly and can vary;

for example, who speaks first when a telephone is answered

differs in different cultures. Such conventions are

established, agreed upon, and then learned by newcomers.

SYSTEM

The system used in this study consisted principally of

Flatland, a flexible, synchronous tele-presentation

environment. NetMeeting, a commercially available

collaboration tool that supports application sharing, was

used primarily for presenting demos and exercises.

Keywords

Distance learning, multimedia presentations

INTRODUCTION

Distance education can help when classroom attendance is

not possible or when students would like to participate

casually while attending to other work. Desktop to desktop

video permits presentations without requiring anyone to

travel. Researchers at Sun Microsystems and elsewhere

have conducted experiments with live multimedia

presentation systems [1,2]. Audience members appreciated

the convenience of attending on their desktop computers,

but felt it was less effective than live attendance, as did the

instructors, who found the lack of feedback disconcerting.

Why the mixed response, given the benefits and

convenience of distance learning? In standard classroom

instruction, a flexible range of communication channels is

available-visual observation, voice, expression, gesture,

passing notes, writing on a board, throwing an object for

emphasis, walking about to view student work. Even with

years of experience, effective teaching is a demanding task.

Knowing which communication or feedback mechanism to

employ at a given moment requires understanding their

effects and social conventions governing their use.

Systems that support presentations at a distance mediate all

awareness and communication digitally. Users must find

new ways to obtain the information or feedback they desire

and to compensate for lost information, and must develop

social conventions and protocols to govern technology use.

Past work has focused on single-session presentations. This

paper reports a study of multi-session classroom use. Users

of complex, collaborative technologies experience a

learning curve as they experience the range and effects of

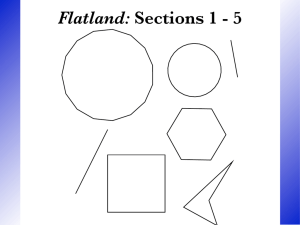

Figure 1 – Flatland Presenter Layout

Flatland presented instructors and students with four major

windows and several additional channels to aid

communication and coordination (Fig. 1). Audio and video

(upper left) went from instructor to students. The upper

right window held slides (and a pointer), either PowerPoint

or instructor-authored interactive slides: students can make

selections, which are tallied. A chat window is in the lower

right and a question queue in the lower left. A student can

support another student’s question with the checkbox.

Other feedback channels are above the instructor image: a

pop-up attendee list, a ‘hand’ with counter (e.g., “Everyone

finished with the exercise please click on the hand icon”),

and too-fast/ too-slow and clear/confusing indicators.

Flatland details can be found in [3].

METHOD

Two technical courses normally presented in a classroom

were given without modification using Flatland. The first

was two 3-hour sessions with 4 students, the second four 2hour sessions with 10 students. Both included live

demonstrations via NetMeeting.

Each instructor presented from a usability lab, permitting

logging of activity; one student in each class was in a

different lab room, the others attended from their offices.

The instructors received a brief demo of the system prior to

their first classes. Following each session, we distributed

surveys and then verbally debriefed the instructor, and

reminded instructors of unused features.

RESULTS

Flatland use changed considerably over sessions.

Confronting an array of communication and feedback

channels to replace those of classroom instruction,

participants tried key features, grew comfortable with them,

then experimented with more effective uses and new

features. Some seemingly desirable approaches were not

used even when pointed out. Students were generally

positive about the system; instructors’ regard increased over

sessions. Both groups suggested improvements.

Changes in behavior and perception over sessions

“Before it was just a feature. This time it was a tool.”

—Instructor 1, discussing ‘hand raising’ after the 2nd class

In his third session, Instructor 2 began to make heavy use of

dynamically created slides and respond promptly to the

question queue. In session 4 he began monitoring the chat

window during the lecture. Both instructors steadily

increased pointer use. In the second class, student chat

discussion shifted from a focus on Flatland to the course,

rising from 27% to 60% class-related.

After each class, instructors were asked how well they

thought they handled student questions. Instructor 2

responded 3, 4, 4, 5 on a 1-5 scale over sessions. Asked to

what extent Flatland interfered, his responses were (no

response), “too early to say”, 4 (high), 2 (low). Asked how

distracting Flatland was, student ratings fell from 2.8 to 1.7.

What drove changes in behavior over time? We identified

two major factors: ambiguity about which channel to use

for particular information, and uncertainty or incorrect

assumptions by the instructor about the student experience,

and vice versa. The widespread failure to appreciate the

other side’s experience is due to lack of full understanding

of features, to differences in equipment configurations, and

to the lack of normal visual and auditory feedback channels

relied on in classrooms. These factors are explored below.

Uncertainty about appropriate channels

“Once the instructor had answered it (a question), I didn't like the

feeling of not being able to say ‘Thank you.’”

—A student discussing the question window feature

Confusions began early. The question window, provided for

students to enter and vote on questions, went virtually

unused in one first session. One student assumed this

window was for the instructor to pose questions. The

instructors saw the hand icon as a mechanism for students

to respond to their queries. Some students used it to “raise

their hand” to be called upon, only to go unnoticed by the

instructor. Student ‘coming and going’ was reported in the

chat window, drawing early attention to it. Students then

used it to report problems, and then to ask questions. Once

the lecture was underway, instructors concentrated on

lecturing and stopped monitoring this noisy channel, so

student questions then went unanswered.

There was a tendency to respond via the same channel that

one is queried. In his first class, Instructor 1 responded to

early chat by typing in the chat window. In the second class

he responded by speaking. Similarly, when instructors

asked for clarifications to question window questions,

students had to choose between typing a non-question in the

question window or in the inactive chat window.

Uncertainty about others’ context and experience

Where the interfaces differed or information was

incomplete, misperceptions arose. Students did not know

how the Clear/Confusing, Too Fast/Too Slow indicators

appeared to the instructor and whether they were

anonymous, and did not use them. One instructor posted an

interactive slide inquiring about exercise status unaware

that it would not be visible under NetMeeting (being used

to do the exercise), and did not understand the lack of

response. Which students remained engaged was unclear.

“Very little feedback from students… For some reason they

seemed reluctant to give comments or participate. This should be

explored as the teacher needs some kind of feedback…”

NetMeeting: “worked very well from my end but would be very

interested how it worked for the students.” – Instructor 1

“In a conventional classroom I have lots of visual cues as to

attention level and comprehension that are missing here. For

instance, if I say something and get puzzled looks, I repeat myself

using a different analogy or different words or a different

approach. Not so easy to do that here.” - Instructor 2

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORK

The development of social protocols is a major challenge

for the designers and users of distance learning systems.

Groups may choose sub-optimal approaches, or approaches

that will clash with others when membership shifts. Should

designers try to build in or guide users to effective

protocols? What will work best, or at all, in different

situations? The results from this initial study should be

followed by more extensive studies, repeated with different

designs and user populations, to identify effective

combinations of features, guidance, and flexibility.

REFERENCES

1. Isaacs, E.A., Morris, T., & Rodriguez, T.K. A Forum

For Supporting Interactive Presentations to Distributed

Audiences, Proc. CSCW’94, 1994, pp. 405-416.

2. Finn, K.E., Sellen, A.J., & Wilbur, S.B. (Eds.). VideoMediated Communication, 1997. Erlbaum.

3. White, S.A., Gupta, A., Grudin, J., Chesley, H.,

Kimberly, G., Sanocki, E. A Software System for

Education at a Distance: Case Study Results, Microsoft

Technical Report MSR-TR-98-61, November, 1998