probability flows

advertisement

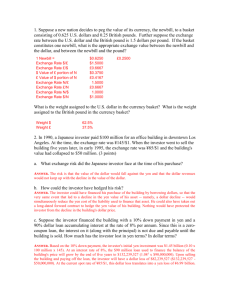

INTERNATIONAL FINANCIAL MANAGEMENT FINAL EXAMINATION 1. A project will cost $1 million today but yield no return for several years. Once the project becomes productive, it will generate cash flows of $250,000 annually forever. Suppose two firms are examining this project, a Japanese firm and a U.S. firm. The foreign project has a beta of .60 for the Japanese firm; the Japanese risk-free return is 4% and the required return on the market is 9%. The project has a beta of 1.25 for the U.S. firm; the U.S. risk-free return is 5% and the required return on the market is estimated at 11%. Approximately how many more years will the Japanese firm wait for the project to generate cash than the U.S. firm? (2 points) ANSWER. We have an investment with cost (I), which eventually generate a cash flow that will continue forever. The net present value of this project is: NPV I 1 1 r t 1 CF r Where: r is the required rate of return, CF ithe perpetual cash flow, t the number of years before the cash starts to flow, and I the initial investment. Hence, to find the number of years the firm can wait for the project to generate cash flows, we: Solve for t : 0 I t ln( 1 1 r t 1 CF r CF ) / ln( 1 r ) 1 I r This gives the following: Project costs: CF every year forever: $ 1,000,000 $ 250,000 Japan Risk free rate Market return Project beta Required rate of return: The number of years the firm can wait for project cash flows US 4% 9% 0.6 7.00% 5% 11% 1.25 12.50% 19.81 6.88 The required rate of return is calculated using CAPM (Ri = Rf + Beta * (Rm - Rf)). The Japanese firm should be willing to wait almost 13 years longer than the American for cash to flow. 2. Suppose a firm anticipates cash flows of $2.5 million, $3 million, and $4 million for years 1, 2, and 3, respectively, on an initial investment in Ecuador of $22 million. The firm expects cash flows of $5 million in years 4 and beyond, forever. If the required return on this investment is 17%, how large does the probability of expropriation in year 5 have to be before the investment has a zero NPV? Expected compensation in the event of expropriation is $3 million. (2 points) Page 2 B Required return C D E F G H 17% p 0.745 Cash Flow in Yr5 (all # in millions) 5 Compensation 3 Years Cash Flows Cash Flows with Expropriation 0 1 2 3 4 5 -22 2.5 3 4 5 5forever -22 2.5 3 4 5 3 1.00 0.85 0.73 0.62 0.53 0.46 Total NPV of 5 forever ($22.00) $2.14 $2.19 $2.50 $2.67 $15.70 $3.19 NPV of Expropriation ($22.00) $2.14 $2.19 $2.50 $2.67 $1.37 Discount Factor Breakeven Probability 22.26% =1-(-H20/(H19+(-H20))) 3. A new project is projected to yield $2.5 million annually in after-tax profit, based on a local corporate profit tax rate of 40%. However, this profit figure depends on the use of a transfer price of $30 per unit on a component bought from the parent. If the project requires 100,000 units of this component annually, the effect on project profitability and on parent profitability of a boost in the transfer price to $35 will be ($300,000) and $21,000, respectively. The parent's marginal tax rate is 34% and the incremental tax on subsidiary remittances to the parent is -3%. (2 points) Parent Parent Transfer Price: Remittance from Abroad: Incremental Tax (-3%): Net Income From Abroad $30 $ 2,500,000 $ 75,000 $ 2,575,000 $35 $ 2,200,000 $ 66,000 $ 2,266,000 Revenue from product: Taxes (34%): Net Income From Product: $ 3,000,000 $(1,020,000) $ 1,980,000 $ 3,500,000 $(1,190,000) $ 2,310,000 Total Net Income: $ 4,555,000 $ 4,576,000 4. In 1990, a Japanese investor paid $100 million for an office building in downtown Los Angeles. At the time, the exchange rate was ¥145/$1. When the investor went to sell the building five years later, in early 1995, the exchange rate was ¥85/$1 and the building's value had collapsed to $50 million. (3 points) a. What exchange risk did the Japanese investor face at the time of his purchase? ANSWER. The risk is that the value of the dollar would fall against the yen and that the dollar revenues would not keep up with the decline in the value of the dollar. b. How could the investor have hedged his risk? ($11.14) 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Page 3 ANSWER. The investor could have financed his purchase of the building by borrowing dollars, so that the very same event that led to a decline in the yen value of his asset -- namely, a dollar decline -- would simultaneously reduce the yen cost of the liability used to finance that asset. He could also have taken out a long-dated forward contract to hedge the yen value of his building. Nothing would have protected the investor from the decline in the building's dollar price. c. Suppose the investor financed the building with a 10% down payment in yen and a 90% dollar loan accumulating interest at the rate of 8% per annum. Since this is a zerocoupon loan, the interest on it (along with the principal) is not due and payable until the building is sold. How much has the investor lost in yen terms? In dollar terms? ANSWER. Based on the 10% down payment, the investor's initial yen investment was ¥1.45 billion (0.10 x 100 million x 145). At an interest rate of 8%, the $90 million loan used to finance the balance of the building's price will grow by the end of five years to $132,239,527 (1.085 x $90,000,000). Upon selling the building and paying off the loan, the investor will have a dollar loss of $82,239,527 ($132,239,527 $50,000,000). At the current spot rate of ¥85/$1, this dollar loss translates into a yen loss of ¥6.99 billion. Adding this loss to the investor's initial down payment of ¥1.45 billion yields a total yen loss for the investor of ¥8.44 billion. d. Suppose the investor financed the building with a 10% down payment in yen and a 90% yen loan accumulating interest at the rate of 3% per annum. Since this is a zerocoupon loan, the interest on it (along with the principal) is not due and payable until the building is sold. How much has the investor lost in yen terms? In dollar terms? ANSWER. If the investor had financed the building with the 90% yen loan, the investor would have had to borrow 100,000,0000 x 0.90 x ¥145 = ¥13.05 billion. At an interest rate of 3%, the ¥13.05 billion loan will grow by the end of five years to ¥15.13 billion (1.03 5 x ¥13.05 billion). The $50 million sale price translates into ¥4.25 billion (50,000,000 x 85). After paying off the loan, the investor has a loss of ¥10.88 billion. Adding to this loss the initial down payment of ¥1.45 billion produces a total loss for the investor of ¥12.33 billion. It can be seen from the answer to part c that the use of dollar financing reduced the investor's loss. The investor, of course, lost anyway because the value of the building declined instead of rising by at least the rate of interest. 5. In 1990, Matsushita bought MCA Inc. for $6.1 billion. At the time of the purchase, the exchange rate was about ¥145/$. By the time that Matsushita sold an 80% stake in MCA to Seagram for $5.7 billion in 1995, the yen had appreciated to a rate of about ¥97/$. (3 points) a. Ignoring the time value of money, what was Matsushita's dollar gain or loss on its investment in MCA? ANSWER. If an 80% stake in MCA was worth $5.7 billion, then the entire firm was worth $7.125 billion. Based on this valuation, Matsushita actually made $1.025 billion on its purchase of MCA. That is, by buying MCA at a price of $6.1 billion and selling it for a price that valued the business at $7.125 billion, Matsushita made $1.025 billion. b. What was Matsushita's yen gain or loss on the sale? ANSWER. Taking into account the differences in exchange rates, Matshushita paid ¥884,500,000,000 (6,100,000,000 x 145) for MCA in 1990 and sold MCA in 1995 for a price that valued it at Page 4 ¥691,125,000,000 (7,125,000,000 x 97). The net result was a loss for Matsushita of ¥193,375,000,000 on its purchase of MCA. c. What did Matsushita's yen gain or loss translate into in terms of dollars? What accounts for the difference between this figure and your answer to part a? ANSWER. Matsushita's yen loss converts into a dollar loss of $1,999,382,000 (193,375,000,000/97). This figure differs from the answer in part a because it takes into account the change in exchange rates between 1990 and 1995. In effect, it asks what would have happened if Matsushita had held onto its yen instead of converting them into a dollar asset that didn't appreciate in line with the yen's appreciation. In other words, this computed dollar loss represents an opportunity cost. 6. Suppose Minnesota Machines (MM) is trying to price an export order from Russia. Payment is due nine months after shipping. Given the risks involved, MM would like to factor its receivable without recourse. The factor will charge a monthly discount of 2% plus a fee equal to 1.5% of the face value of the receivable for the non-recourse financing. (3 points) a. If Minnesota Machines desires revenue of $2.5 million from the sale, after paying all factoring charges, what is the minimum acceptable price it should charge? ANSWER. At a monthly discount of 2%, and an extra 1.5% fee for nonrecourse financing, Minnesota Machines will pay a total fee equal to 19.5% (9 x 2% + 1.5%) of the face amount of its price for factoring its nine-month export receivable without recourse. In other words, after paying all factoring fees, MM will clear 80.5% of the price it sets. Thus, in order to net $2.5 million on its export sale, MM must set a price P such that .805P = $2,500,000. The solution to this equation is P = $3,105,590. This is the minimum acceptable price to MM. b. Alternatively, CountyBank has offered to discount the receivable, but with recourse, at an annual rate of 14% plus a 1% fee. What price will net MM the $2.5 million it desires to clear from the sale? ANSWER. If MM decides to discount the receivable with CountyBank, it will pay a total fee equal to 11.5% (.75 x 14% + 1%). Thus, in order to net $2.5 million on its export sale, MM must now set a price P* such that .885P* = $2,500,000, or P* = $2,824,859. c. Based on your answers to parts a and b, should Minnesota Machines discount or factor its Russian receivables? MM is competing against Nippon Machines for the order, so the higher MM's price, the lower the probability that its bid will be accepted. What other considerations should influence MM's decision? ANSWER. Based purely on net revenue, MM should plan on discounting its receivable. However, this would expose it to credit risk. Credit risk reduces MM's expected revenue from this sale (at the extreme it may receive nothing, if Russia defaults). This brings up two issues. First, is the price charged by the factor reasonably reflective of the risk of default or delay in receipt of payment? If so, then MM's expected revenue from the sale at a given price will be the same from discounting or factoring even though the most likely revenue will differ. Second, how risk averse is MM? The more risk averse it is, the more reason for factoring its receivable. Most likely, the factor is charging a fair price for the risks involved. In that case, MM will be receiving the benefits of the factor's credit risk analysis and collection skills. In fact, as pointed out in the text, the cost of bearing the credit risk associated with MM's Russian receivable may be Page 5 substantially lower to the factor than to MM. If so, then MM will actually get a better deal with factoring then with discounting. A more important issue here is the price that MM should charge. Although MM desires revenue of $2.5 million from this sale, that may not be its minimum acceptable revenue. As a Japanese firm, Nippon is likely to focus on market share and so will probably compete very strongly on price. MM will therefore have to price its sale as low as possible. In setting a price, MM should consider the possibility of future sales stemming from this initial order. To the extent that there will be follow-up orders for additional units, parts, and service, MM might consider settling for a lower profit this time around in the expectation that it will make higher profits on future sales. d. What other alternatives might be available to MM to finance its sale to Russia? ANSWER. MM may be able to take advantage of a government export-financing agency to provide it with lower cost funds. Alternatively, MM may be able to receive low-cost government export insurance, thereby eliminating credit risk at a relatively low price.