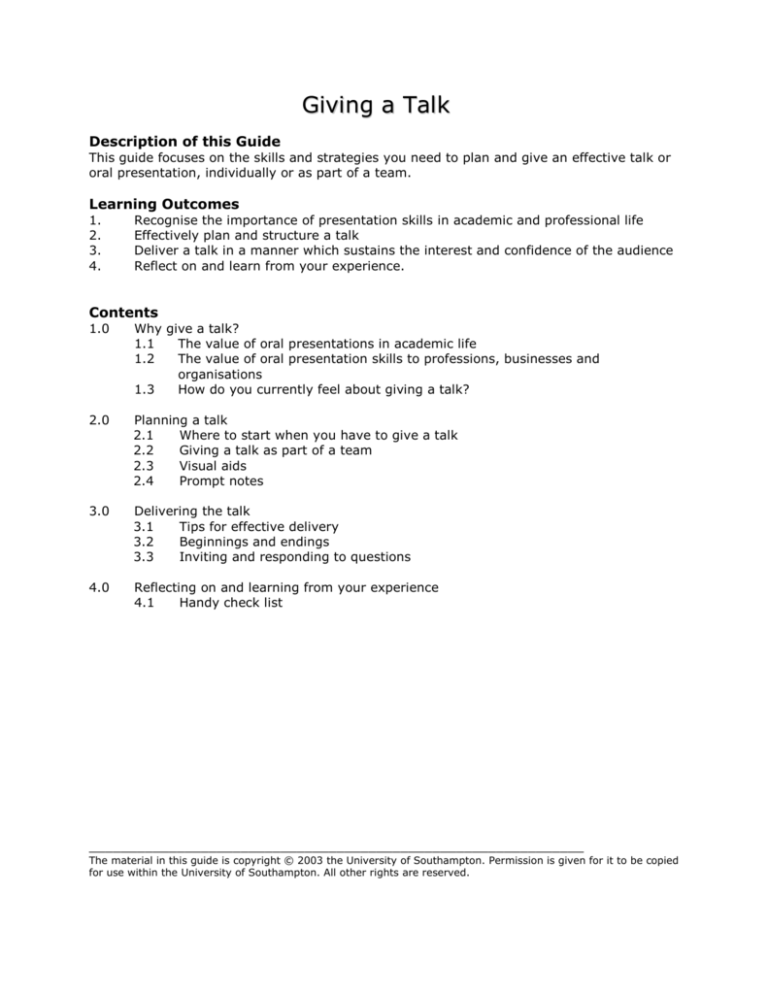

Giving a Talk

Description of this Guide

This guide focuses on the skills and strategies you need to plan and give an effective talk or

oral presentation, individually or as part of a team.

Learning Outcomes

1.

2.

3.

4.

Recognise the importance of presentation skills in academic and professional life

Effectively plan and structure a talk

Deliver a talk in a manner which sustains the interest and confidence of the audience

Reflect on and learn from your experience.

Contents

1.0

Why give a talk?

1.1

The value of oral presentations in academic life

1.2

The value of oral presentation skills to professions, businesses and

organisations

1.3

How do you currently feel about giving a talk?

2.0

Planning a talk

2.1

Where to start when you have to give a talk

2.2

Giving a talk as part of a team

2.3

Visual aids

2.4

Prompt notes

3.0

Delivering the talk

3.1

Tips for effective delivery

3.2

Beginnings and endings

3.3

Inviting and responding to questions

4.0

Reflecting on and learning from your experience

4.1

Handy check list

______________________________________________________________

The material in this guide is copyright © 2003 the University of Southampton. Permission is given for it to be copied

for use within the University of Southampton. All other rights are reserved.

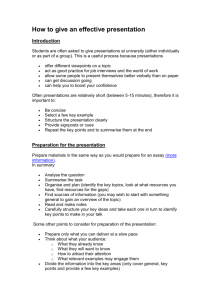

Giving a Talk

Skills

Giving a Talk

Talks or what are often called, more formally, oral presentations are an integral part of

academic and professional life. Some people become anxious about having to give a talk,

but there is nothing mysterious about being an effective speaker; talks involve the

application of techniques that can be planned and rehearsed. This resource helps you to

understand what tutors are looking for and how you might plan and deliver a talk at any

stage in your academic and professional life.

The following advice is made up of four parts:

1.

Why give a

talk?

Speaking about

what you know is

a highly effective

learning activity

Talks are an

integral part of

academic life

Presentation

skills are highly

valued by

professions,

businesses and

organisations

2.

Planning your

talk

3.

Delivering

your talk

4.

Reflecting

on your

experience

Considering how your

talk will be assessed

Using a checklist of tips

for effective delivery

Researching your topic,

selecting ideas and

supporting evidence, and

shaping the talk into a

coherent argument

Establishing clear

beginnings and endings

Use a checklist to

evaluate your own

performance after

you have given your

talk

Thinking ahead about

room layout and use of

visual aids, and preparing

accordingly

Preparing to invite and

respond to questions

Make notes about

what you might do

differently, if

anything, next time

Considering ways of

formatting ‘prompts’ to

help you through the talk

Using visual aids

Writing ‘prompt notes’

Please note that you will find a certain amount of repetition in this guide. This is deliberate

and is intended to reinforce key points and/or to allow for the fact that you may not read the

guide from beginning to end but simply dip into it.

2

Giving a Talk

Skills

1.0

Why Give a Talk?

Being able to give a good and clear presentation to a public audience is a skill that you and

your future employer will greatly value in a wide range of situations. Oral skills, alongside

writing and research skills, teamwork, and time management, are aspects of your degree

course, or (key) transferable skills, which will have application to your future career in

whatever field that may be. Prospective employers always ask for these key skills in

references, and they can be seen as more important than the subject of your degree, so

when you are asked to give a talk think about how to develop the skills involved in doing

this well – not just about the topic you will be talking about.

When tutors ask you to give a talk as part of your programme of study, it may be an

informal talk, which becomes one of the learning activities experienced by you and your

fellow students, or it may be a formally assessed talk which counts as part of your overall

mark for that study unit.

1.1

The value of oral presentations in academic life

In this section you are asked to reflect upon your attitude towards communicating orally

in formal academic settings.

Which of the following statements are true for you?

Yes/No

A

I prefer to write rather than to talk about my subject, because I

have had more practice at writing and can do it in my own time.

B

Being able to express myself clearly in speech will help me think

clearly, and vice versa.

C

If I know I have to talk about something, I will definitely do some

preparation, because I don’t want to stand in front of others with

nothing to say!

D

If I’m interested in and knowledgeable about something, I find it

easier to talk about it.

E

Explaining things to other people helps me understand them better

myself.

People have different kinds of strengths when it comes to writing and speaking. You may be

very happy just getting on with written assignments, or you may be glad to prepare a talk

because you find that you are much better at explaining things aloud than you are at writing

them down. Whatever your particular preferences, research shows that speaking to others

3

Giving a Talk

Skills

about concepts and information helps you learn – it helps you change and grow in familiarity

with the language of your subject discipline, which in turns helps you increase your

knowledge, understanding and skills in that area in the future. Grasping an academic

discipline is a bit like learning a foreign language; speaking it aloud is the best way to learn.

That is why, if you want to become increasingly involved in academic life, you will be asked

(for example, as a postgraduate student) to give papers at conferences, where you will

listen to and give talks to others with similar interests. Having to give a talk as part of your

programme of study will prepare you for this.

1.2

The value of oral presentation skills to professions, businesses and

organisations

It may well be, however, that you are planning to move out into the workforce as soon as

your course has finished, and you do not plan to stay involved in academic life. If that is the

case, you should take oral presentation skills just as seriously, as employers and

organisations everywhere ask for confidence and skills in the areas of interpersonal

communication and presentation. There are very few occupations and professions that do

not require these skills, and remember that being interviewed in person in order to get a job

is very largely about demonstrating your ability to answer and ask questions and,

increasingly, give a short presentation. You are also very likely to progress in your

workplace if you have good oral skills; the ability to speak and listen appropriately and

effectively is linked to the ability to work effectively with and to inspire others, whether they

are colleagues, clients or customers.

Both for learning and for your future professional life, speaking skills are so important.

1.3

How do you currently feel about giving a talk?

For a moment consider the numerous talks and lectures you have listened to during your

life and:

List some characteristics of the talks you enjoyed:

List some characteristics of the talks that bored you:

4

Giving a Talk

Skills

When you give a presentation what do you think are your strong and weak points. ?

2.0

Planning a Talk

As with so many things, giving an excellent talk is largely about thinking ahead and

thorough preparation.

If you have been asked to give a talk, check that you have been given the following

information.

Yes/No

A

The date, time and length of the talk

B

Roughly how many people will be in the audience, and where the talk

will take place (the kind of room, facilities available and so on)

C

What your topic will be, or the area from which you must choose a

topic, and how to research it effectively

D

How your talk will be assessed – which criteria will be used to assess

it, and whether or how much it will contribute to your mark for that

unit of study

If you did not tick ‘A’ then make sure you get that information as soon as

you can. In particular, knowing the length of time you have to speak (a

minimum and a maximum, if possible) will enable you to select the right

amount of material for your talk. You may be worrying about having

enough to say, but remember that a common mistake is to select too much

material and to try to cram it all in, so that the audience members are

overwhelmed with too much information which they cannot follow.

If you did not tick ‘B’ then, again, make sure you get hold of that

information. Decisions about things like visual aids and use of supporting

handouts will depend in part upon knowing how many people will be there,

and whether certain pieces of equipment might be there, such as a

whiteboard or an overhead projector.

5

Giving a Talk

Skills

If you did not tick ‘C’ then as a matter of priority find out more about

what topic you should be preparing by talking to or emailing the relevant

tutor. However well you expect to entertain the audience with your

speaking skills, the talk will not be effective if you have nothing relevant

to say! Remember that you will probably need to find supporting evidence

for the things you say, just as in written assignments, and that you can

use the same ‘search skills’ for a talk as you need for an essay or project.

Look at the Developing an Effective Search Strategy Guide to help with

this aspect. You will also need to construct an argument, or a train of

thought running through what you say, so that the talk hangs together

with a logical shape and a clear beginning, middle and end. For more tips

on how to construct a logical argument see the Writing Effectively Guide.

If you did not tick ‘D’ then ask your tutor to explain how you will be

assessed. Many tutors use checklists similar to the one in Section 4.0 of

this guide. Have a look at this now if you are unfamiliar with such

checklists. The more detail you have about the assessment criteria used

for your talk, the clearer you will be about what is expected. For

example, what proportion of the mark will be given for the style and

delivery of your talk, and what proportion for your research and the

content?

2.1

Giving a presentation as part of a team

You may be asked to work with others to give a talk or presentation; all of the advice in the

other sections should be useful for you and your team as you prepare, but bear in mind also

the following tips particularly aimed at group or team presentations:

PLAN THE TALK TOGETHER

Decide collectively how it will be structured, and who will be

responsible for which part of the talk.

SET RESPONSIBILITIES

Decide on who will be responsible for all of the elements of planning

– go through the list of ‘Twelve Preparation Tasks’ in Section 2.2

and work out who will be responsible for what, and by when.

VISUAL AIDS

Make sure you all know who will be preparing – and then using each kind of visual aid, and that you can all use equipment such as

the overhead projector, in case anyone has to drop out at the last

minute.

PHYSICAL LAYOUT

Before you give the talk, work out exactly where each of you is

going to stand, and how you will move on from one section of the

talk to the next. Introducing each other by name is a good idea –

for example, you may want to say something like, “I’m now going

to hand over to Rachel, who will tell you more about X, an aspect of

the topic which she has been researching.”

PRACTISE

Practise giving the talk together beforehand – even if it is to an

empty room – just to make sure that you all have the same things

in mind in terms of what you are collectively saying, and how you

are saying them. The more familiar and relaxed you are with each

other, the more relaxed and convincing your presentation is likely

to be for your audience.

6

Giving a Talk

Skills

For further guidance on working collaboratively, see the Working in Groups Guide.

2.2

Where to start when you have to give a talk

Firstly, remind yourself that giving a talk is NOT the same as writing an essay that you then

read out. Reading aloud from a script will result in poor marks for the ‘communication skills’

aspect of the marking scheme. So, writing an essay and then reading it is not an option!

What you will need is some form of notes – perhaps ‘prompt cards’, unless you are confident

enough to rely on overhead projector transparencies with notes on, or something like

PowerPoint, a software presentation package. Skills in using this kind of equipment can be

gained in a variety of ways – ask your tutor for advice, if you want to learn how to use it.

For a shorter, more informal talk, cards with ‘prompt notes’ on are probably still easiest. A

talk is about communicating with a particular audience by talking to them, just as you would

talk to a group of friends, but with a little more formality and structure. No one wants to

hear written English read aloud – it always sounds stilted, and it is easier to read it than to

listen to it! Free speech is much more interesting, and it does not matter about the odd ‘um’

or ‘err’ – that’s natural

If you really feel too nervous to talk from prompt cards, and

you feel you must have the written text then (but not a whole

essay):

large print

1. Read from a paper with

as this will

slow you down and prevent you from gabbling.

2. Physically layout the text in small chunks that remind you

to pause and LOOK at your audience

3. Put a note in at each point for a pause and look at the

audience.

4. Make sure you don’t gabble, you pause and you look at

the audience – make eye contact with a few people, you will

feel better and so will they!

Keeping these points in mind, you can set about planning your talk. We all have different

methods of planning. You may want to have a large piece of blank paper in front of you,

some separate cards to make notes on, or just a blank word-processing document on a

computer screen so that you can create a list of bullet-points. If you find these too

daunting, you can use an audio-tape to talk to yourself about what you need to do to

prepare, the main points you might want to include, and so on. Some people find that doing

this, then playing back the tape, is really helpful! Others prefer spider diagrams or sticky

paper notes, to help play around with ideas.

7

Giving a Talk

Skills

To help with the preparation of your talk use the following activity to scope what needs to be

done and to monitor progress.

Aspects of the task you may want to explore, depending on your particular situation and the

requirements of the talk, include those listed in the grid below. While you are working on

the talk, tick the boxes once that aspect has been covered.

Twelve preparation tasks

To do

Doing

Now

Done

In the weeks or days before the talk

1 Decide on a title for your talk (even if a rough

idea at this stage)

2 Research the topic, so that you know enough about its

background to feel confident with your particular angle on it.

See the Developing an Effective Search Strategy Guide for

more on this.

3 Refine and narrow the topic so that you have a few main

points or headings (usually between three and seven,

depending on the length of the talk – a common structure is 3 x

3; 3 main points with 3 sub-points) on which you can elaborate,

together with supporting evidence for your argument or train of

thought. Make sure that your talk has a clear beginning, middle

and end. Try to begin with something memorable.

4 Write brief notes onto ‘prompt cards’ to help make sure that

you cover the ground you intend to, and in the right order

(unless you are using an aid such as the software presentation

package PowerPoint, which will allow you to create notes pages

as part of the package).

5 Look carefully at the assessment criteria to be used by the

tutor (particularly if your talk is to be formally assessed)

6 Check out the venue for the talk and making sure that you

know where you will want to stand or sit, where you will want

your audience to be, and what equipment you may want to use

to enhance the talk

7 Decide on the visual aids you will use, and preparing these

(see Section 2.3 below)

8

Giving a Talk

Skills

8 Practise giving your talk and timing it – either to a friend, to

a mirror or to a tape recorder (audio or even video) – then

editing it as appropriate.

On the day of the talk

9 Re-read your prompt notes and any supporting material,

such as handouts you have prepared for the audience, to make

sure that you are feeling familiar with your topic and that they

complement each other

10 Check that handouts and visual aids are all to hand, and

that the venue is appropriately set up, with any equipment

needed

11 Remind yourself of the simple but vital rules for effective

oral communication listed in 3.1 below

12 Relax, breathe deeply and remember that your audience is

on your side!

As you assess what stage you have reached with each task make sure that

you keep in mind how it contributes to the end product. There is always a

danger of ‘losing the plot or the big picture’ when boxes are ticked in a

mechanistic fashion.

2.3

Visual and auditory aids

Depending on the kind of talk you are asked to give, there are numerous possibilities for

visual or auditory aids. A selection is listed below, so that you can consider their feasibility

for your situation. Alongside the selections is some brief advice about how to use – and not

to use – these.

Visual Aid

Advice

Whiteboard or

blackboard

Practise using these before the day, to check the legibility of your handwriting and the

size of writing needed. Do not write too much – just key phrases or short bullet

points. You can use boards to stick up pictures or posters. Do not stand between the

board and the audience, and do not talk to the board.

Posters

These can be very effective but will need to be well planned beforehand. Do not cram too

much into a poster – space between the text and pictures is very important if the poster

is to have impact, and if it is to communicate clearly.

Handouts

Keep these short (no more than 2 sides of A4) and use bullet points or other short

sections of text, illustrated where appropriate. Do not write an essay on a handout; use it

to summarise and note key elements of information such as technical terms, quotations

and references.

Quiz sheets

A few questions to facilitate audience participation and to reinforce key points can be

useful as a warm up or concluding activity (if time permits). Make sure the questions are

relevant and interesting!

Overhead projector

transparencies

Prepare these beforehand. You can print onto them from a computer, but if you do this

ask a technician for advice about using the right kind of acetate transparency. To

photocopy onto acetate it is essential that you use the correct kind, or you will cause

great damage to the photocopier. Be sure to ask for advice. Remember that ‘less is

more’ on transparencies – make sure that writing is large enough when projected, and

that you do not cram too much onto one slide.

9

Giving a Talk

Skills

Objects of interest

(sometimes referred to

as ‘realia’)

Using real objects as visual aids can be very effective; for example, a garment on a textile

conservation course, or an artefact on an archaeology course. Using objects can be

connected with demonstration of a process, for example the use of a particular piece of

equipment

Audio-tape recorder or

musical instruments

and so on

Again, where appropriate the use of auditory material can be very interesting. Make sure

that you have checked and practised on any equipment used, well before you start.

Video,DVD,film,

transparency slides or

similar

As above, check all equipment beforehand. Do not overuse pictures or video – keep them

short and strictly relevant to your argument.

Multi-media

projector

These can be used to project computer screens, and therefore to show the internet, or

software packages such as PowerPoint. Ask for advice about the suitability of using

these, or about opportunities for learning how to use them.

The most important thing about all of these aids is that they need to be tied in with your

presentation:

Visual aids are used to illustrate a point that you have made (or are about to make) in your

presentation. Avoid using them as a kind of visual wallpaper, for example by ending your

talk by showing a transparency without commenting on it.

Choose transparencies to display items such as key points, graphs, grids, statistics,

illustrations and photos.

If you use video clips, use them economically: do not show about ten extract. If you have

a limited time for your presentation, use perhaps only one to three clips.

Have your visual aids ready to use and in the right order.

Introduce visual aids and speak to them. For example, you could say:

I am now going to

show you

2.4

What I want to show

you here is...

Prompt notes

The trick with writing effective prompt notes for a talk is to write notes, not full sentences

that you have to read out word for word. Dividing these notes onto a sequence of cards is

more helpful that using large sheets of paper; your eyes will get confused looking at a wide

expanse of notes, whereas on a small card they will quickly spot the next heading on which

to elaborate. So, for example, if you were giving a talk on how to give an effective talk, one

of your prompt cards might look something like this:

10

Giving a Talk

Skills

Engage with your Audience

Introduce yourself

Smile and sound interested

Develop eye contact

Tell audience the structure of your talk

Use the right language for your audience

Maintain right pace

Use your voice and pauses to move between points

Use notes to move you from one point to next

If you need to make academic references, rather like you would have to in an essay, then

refer to the reference briefly on your card, but keep a separate list of quotations from which

to read. You might find it useful to incorporate quotations and references into a handout for

your audience – they can then refer to these later. The same advice holds true for detailed

evidence, such as complex graphs and statistics, used to back up your argument. (See the

Referencing Your Work Guide for details on how to reference accurately and appropriately.)

3.0

Delivering the Talk

The effectiveness of your talk will depend upon two main factors:

1.

The extent to which you have researched and understand the topic you are talking

about

2.

The extent to which you engage with and interest the audience in that topic.

Over-concentration on the first factor at the expense of the second will seriously undermine

the quality of your presentation. While the adage ‘It’s not what you say, it’s the way that

you say it’ should not be taken to extremes it does contain an element of truth.

3.1

Tips for effective delivery

It takes time and practice to become an effective and confident presenter. One suggestion

is to think of presenters who have impressed you when you have been in the audience

and seek to emulate them. Alternatively, you may have had experience of poor presenters

and aspects of delivery you would seek to avoid! Check what you wrote in section 1.3

earlier.

11

Giving a Talk

Skills

One tutor has given the following advice to his students about how to ‘get it right’. Read

each tip or pointer and tick the box alongside it if you are already confident that you can

do this well.

Tick

1

Speak in a lively and engaged way, so that you avoid monotonous delivery. Speak loudly

enough, and with a voice that has appropriate variety of tone, and with a choice of language

appropriate for that audience in that context – not too slangy, but not too formal either.

2

Do not speak too quickly, but keep a steady pace and allow your material to ‘sink in’.

3

Make frequent eye contact with your fellow students. Address them as your audience - not just

the lecturer. Smile appropriately.

4

If at all possible, stand up while giving your presentation. If you prefer to sit down, try not to

look down too much, or hide behind your notes. Choose a seat where you face your

audience, rather than blend into it.

5

At the beginning of your presentation, outline in a few words the aims of your presentation.

When doing a joint presentation, the first speaker should explain how the different parts will fit

together. It is essential that you co-ordinate your part of the presentation with your copresenters in advance, so that you avoid overlaps, or a presentation that appears disjointed.

6

Distribute a prepared handout where appropriate. This handout should give a run down of your

presentation, preferably numbered or in bullet points, and it should have a title. In any case it

should be structured, and easy to read and follow. A handout is NOT identical with your notes,

nor an essay, but a condensation of your presentation, so do not have more than one to two A4

pages. Use illustrations only if they relate to your argument or if you refer to them.

7

If you use (particularly lengthy) quotations from secondary sources, print them in full on your

handout, as your audience can then follow them easily. When you come to these quotations in

your presentation, tell your audience they can find them on their handout.

8

Also list on your handout all names and specific terms you mention in your presentation,

particularly those that your audience may find difficult to note down without seeing them spelt

out (for example, foreign names and technical terms).

9

Concentrate on arguments or developments, rather than simple facts. What is your angle on the

topic?

10

To facilitate a subsequent discussion, you can end your presentation with a number of

conclusions, or even better with a set of questions that emerge from your research. This is

particularly important when you are dealing, for example, with theoretical arguments or texts,

which you may not agree with, or which you do not fully understand. Do not try to gloss over

this, but use it instead as a way into the discussion with your audience. For example:

I don’t think I fully understand what X means when s/he argues... How did you interpret this...?

What do you make of...?

This will help clarify matters both for you and your fellow students who may indeed have similar

problems.

Don’t worry if you have not ticked many or even any of the pointers. Many

of them can be worked on. If you do this consistently and conscientiously

over time you should grow in confidence and ability. If you have a ‘dry

12

Giving a Talk

Skills

run’ with your tutor or friends, you could ask them to look at certain

aspects of your talk on which you would particularly like feedback.

Dealing with Nerves

3.2

Be well prepared – that will make you feel more

confident about your material

Use prompt cards if you can, if not read text –

but see 2.2 above.

Breathe deeply before you start, this slows your

heart rate down and you should feel less nervous

Look at your audience – despite what you may

think, this does calm you.

Pause between points or slides, this allows the

audience to catch up, and gives you some time to

prepare the next part.

Smile and look relaxed, it should create a more

relaxed atmosphere for you (and your audience).

Beginnings and endings

It is worth dwelling for a moment on the importance of the beginning and ending of your

talk. Some public speakers say that you should structure your talk by:

‘saying what you are going to say’,

then ‘saying it’,

then ‘saying what you said’.

While you do not want to fall into the trap of saying everything three times (!), it can be

very helpful to start by describing your aims for the talk, and giving the main headings to be

covered. Then you work through the talk, and finish off by very briefly reminding everyone

of the key headings you have covered.

3.3

Inviting and responding to questions

Prepare beforehand for the moment when you have finished and you want to invite

questions. How will you actually conclude your talk, and how will you then ask the audience

if they have any questions? A common ‘awkward’ moment in talks is when the speaker has

finished, and people do not know whether they can then ask something. How will you avoid

this?

Likewise, if you receive no questions from your audience, what will you do? You could ask

one or two yourself. For example, were you clear about…? and so on. Or, if you are brave,

you could ask the audience specific questions with a view to determining how much they

13

Giving a Talk

Skills

have taken in – in other words, assess the effectiveness of your presentation. Think ahead

about how you will handle this.

You can even write down what you want to say at these tricky points on your prompt cards.

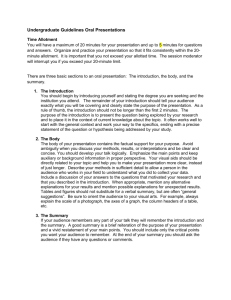

4.0

Reflecting on and Learning from Your Experience

Once you have completed your talk you may just want to heave a sigh of relief and forget all

about it, but you will really benefit from evaluating your own performance, as well as

reflecting on any feedback received from your tutor or assessor and your audience

members. Also remember that there is no such thing as a perfect presentation and there is

always room for improvement. This applies as much to lecturers as to students!

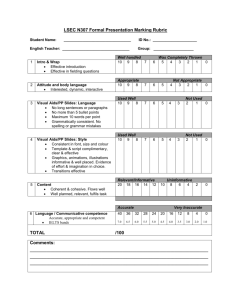

The following checklist gives an example of the criteria your tutor may use to assess oral

presentations. Do not forget that the criteria used in relation to your talk may be rather

different, and the weighting given to the different elements can vary; use your own tutor’s

assessment sheet if you can. However, the checklist below gives you a feel for the kinds of

assessment criteria used.

14

Giving a Talk

Skills

Student presentations: tutor assessment sheet (An example)

You need to check the assessment sheet your tutors will be using.

Planned learning

outcomes

Academic content

Knowledge and

understanding of core

material

Extent, quality and

appropriateness of

research

Conceptual grasp of

issues, quality of

argument and ability to

answer questions

Quality of management

Pacing of presentation

Effective use of visual

material -whiteboard,

visual aids, handouts (as

appropriate)

Organisation and structure

of material (intro; main

body; conclusion)

Quality of

communication

Audibility, liveliness and

clarity of presentation

Confidence and fluency in

use of English

Appropriate use of body

language (inc. eye

contact)

Listening skills:

responsiveness to

audience

Level of attainment

High

average

Tutor’s comments

low

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9 8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

10

9

8 7

6

5

4

3

2

1

Checklists of this kind can be used very effectively for self-evaluation purposes.

15

Giving a Talk

Skills

Use the self-evaluation form on the next page, which is very similar to the one above, to

keep a check of how you are developing your skills. You may want to use this for practice

with your friends – you could fill in the sheet for each other. It is advisable to do this when

practising for your team presentation.

Finally there is a handy checklist of all the things you should think about when giving a

presentation.

16

Giving a Talk

Skills

Oral Presentation: student self-evaluation

Name:

Date:

Unit:

Presentation topic:

Planned learning

outcomes

My strengths in this

area

Things to work on

for next time

Academic content

Knowledge and understanding

of core material

Extent, quality and

appropriateness of research

Conceptual grasp of issues,

quality of argument and ability

to answer questions

Quality of management

Pacing of presentation

Effective use of visual material

-whiteboard, visual aids,

handouts (as appropriate)

Organisation and structure of

material (intro; main body;

conclusion)

Quality of communication

Audibility, liveliness and clarity

of presentation

Confidence and fluency in use

of English

Appropriate use of body

language (inc. eye contact)

Responsiveness to audience

and ability to answer questions

Overall comment:

Once completed this checklist should serve as a valuable resource for the

next occasion on which you are required to give a presentation. Make sure

that it is readily accessible and use it as the starting point for your

planning.

17

Giving a Talk

Skills

4.1

Handy check list

Preparing the content of your talk

The organisation of your talk

Who is your audience?

What are the objectives/aims of this talk?

Find the sources, read, cut down and trim for

talk

Develop a ‘line’, ‘argument’ , ‘thread’

Argue your thread tightly.

Reference well (especially if academic talk)

Impose a structure: beginning, middle and

end

Explain structure and aims of talk to

audience

Use the ‘beginning’ to gain audience

attention, but make sure it is pertinent to

your argument

a quote

a startling fact/opinion

a question

a picture/video sequence/sound

Make points within the ‘middle’ clear, well

defined and neatly linked.

The ‘end’ section is your ‘take-homemessage’. What do you want your audience

to remember? What’s your main message?

Delivering your talk

Be as natural as possible as this will relax you and allow you to be more spontaneous.

Pace

Visual Aids

When nervous you can speak too fast. Deep

breathing should slow you down.

Try speeding up if you have a tendency to

speak very slowly.

Don’t read from a sheet: you will be

monotonous, talk too fast and have little eye

contact with the audience.

Don’t adlib, it could go wrong (unless you are

very confident).

Use prompts from: cards or visual aids to

talk from (or large print in text to slow you

down).

Don’t be afraid to stop and think for a few

seconds.

Build in questions to the audience (even if

you just ask them to think) to slow pace.

Check for EGO (Eye Glazing Over) of

audience… make changes when you detect it!

Visual aids: OHP or computer aided delivery

(.e.g. PowerPoint)

Visual prompts help you and show structure

to audience.

Computer aided delivery allows for

multimedia presentations.

Understand the equipment you will need

(from OHPs to computer leads)

Make sure you have the correct equipment

(& it works).

Check size of room, potential audience and

select correct font size (use approx 35-40)

for slides.

Have clear uncluttered visual aids.

Put graphs etc on to a handout.

Don’t use prose unless really pertinent, and

then give them time to read it.

Don’t use too much colour, it is distracting.

Give out handouts necessary for talk

BEFORE, give out additional material

AFTER.

Contact with audience

Voice/language

Look at your audience when you come in.

Avoid a hostile posture: hunched shoulders,

arms across chest, standing on one leg!

With nervousness the pitch of the voice

rises. Deep breathing should control this.

18

Giving a Talk

Skills

Develop a rapport through your opening and

talk TO rather than AT your audience.

Skim the whole audience, don’t just look at

the same section.

Try and find some friendly faces at the back

(in several areas) to give the appearance of

looking at the whole group.

Be relaxed and this will relax your audience.

Handling questions

Questions during your talk. Make sure you

get back on track. Don’t let such questions

go on too long… use to clarify points rather

discussion (unless talk designed that way).

Questions after talk are more discursive… be

prepared to talk on theme beyond your talk,

e.g implications of things you said, other

views, where to get more information.

Be honest if you don’t know an answer.

Be polite if someone tries to put you down don’t enter into a row.

Make sure questions are not controlled by

one person.

Stay in control of question time and know

when to finish (check for EGO).

Don’t let your talk peter out through a long

question time.

Vary you tone. A monotonous tone gives an

EGO audience.

Vary tone according to content:

louder to emphasise important points

use pause to indicate a change of

direction, or ‘pause for thought’

clear diction - don’t allow sentences to

tail off - keep volume till end of

sentence.

Use language markers (“And now….”,

“The next point….” ) etc plus voice tone

to indicate a change/new point.

Don’t use cliches, empty worn out

phrases.

Add your own tips here & things

you need to work on.

19