The Heresy of Spinoza - Unitarian Universalist Church of Akron

advertisement

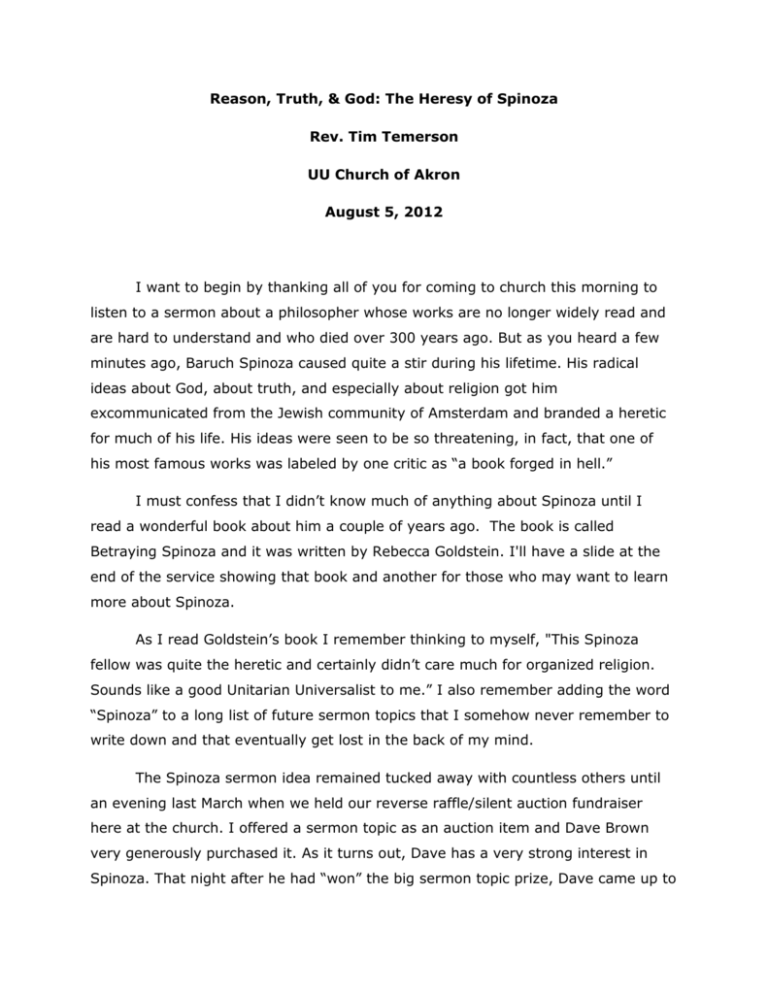

Reason, Truth, & God: The Heresy of Spinoza Rev. Tim Temerson UU Church of Akron August 5, 2012 I want to begin by thanking all of you for coming to church this morning to listen to a sermon about a philosopher whose works are no longer widely read and are hard to understand and who died over 300 years ago. But as you heard a few minutes ago, Baruch Spinoza caused quite a stir during his lifetime. His radical ideas about God, about truth, and especially about religion got him excommunicated from the Jewish community of Amsterdam and branded a heretic for much of his life. His ideas were seen to be so threatening, in fact, that one of his most famous works was labeled by one critic as “a book forged in hell.” I must confess that I didn’t know much of anything about Spinoza until I read a wonderful book about him a couple of years ago. The book is called Betraying Spinoza and it was written by Rebecca Goldstein. I'll have a slide at the end of the service showing that book and another for those who may want to learn more about Spinoza. As I read Goldstein’s book I remember thinking to myself, "This Spinoza fellow was quite the heretic and certainly didn’t care much for organized religion. Sounds like a good Unitarian Universalist to me.” I also remember adding the word “Spinoza” to a long list of future sermon topics that I somehow never remember to write down and that eventually get lost in the back of my mind. The Spinoza sermon idea remained tucked away with countless others until an evening last March when we held our reverse raffle/silent auction fundraiser here at the church. I offered a sermon topic as an auction item and Dave Brown very generously purchased it. As it turns out, Dave has a very strong interest in Spinoza. That night after he had “won” the big sermon topic prize, Dave came up to me and simply said “Spinoza.” For an instant I had a brain freeze and thought that Dave was giving me a new nickname. Not that I would have minded. I mean, what UU minister wouldn’t want to be compared to a famous heretic! That’s a badge of honor for us! But, alas, my brain thawed out and I soon realized that Dave was giving me my sermon assignment rather than promoting me to professional heretic! A few minutes ago I read that very harsh decree of excommunication issued against Spinoza by Congregation Talmud Torah in Amsterdam in the year 1656 when the philosopher was only 24. Wasn’t that language something? Spinoza wasn’t simply being excluded or shunned; he was damned and cursed and it was left to God to blot out his name for all eternity. What brought on such a severe punishment and such harsh language? What could have been so dangerous, so heretical, and so threatening about a quiet, studious 24 year old that would lead the religious community of his childhood and youth to fear and condemn him in such harsh terms? I think we can begin to understand the fear and consternation Spinoza caused not only in his religious community but throughout much of Europe if we look at the language in the second reading. Spinoza speaks of the futility and emptiness of ordinary life and the fact that humankind is so often driven by unreal fears rather than what he calls “the true good.” I think it’s safe to say that much of Spinoza’s philosophy is aimed at unmasking those unreal fears and challenging the ideas and institutions he thought responsible for them while, at the same time, providing humanity with a more objective and reasoned understanding of reality and a path leading in a very different direction – one of joy, happiness, and the true good. Now while we mostly remember Spinoza as a philosopher, there can be little doubt that much of his writing is motivated by and directed at the beliefs, the institutions, and what he saw as the very negative role played by organized religion. To say that Spinoza had a critical view of religion is an understatement. He blamed religion, and especially what he saw as the religious mindset of superstition, irrationality, and exclusiveness, for much of the war, the misery, and the suffering that plagued, and I might add, still plagues, humankind. Although Spinoza’s very negative view of religion put him in conflict with his Jewish community and eventually led to his excommunication, those views was deeply rooted in Jewish history, and especially in the experience of violence and oppression shared by most in the Jewish community living in Amsterdam. You see, many of the families in that community were recent émigrés who had been forced to flee religious persecution in Spain and Portugal. Many like Spinoza’s family were so called “conversos” – Jews living in Spain who had been forced either to convert to Christianity or leave Spain forever. Converting did not offer Spanish Jews like the Spinoza's much security as the violence and torture associated with the Spanish Inquisition was increasingly directed at them. At first, the conversos to fled to Portugal, including Spinoza’s family. But by the second half of the 16th century, even Portugal had also been swept up in the furor of the Inquisition which lead many, including Spinoza’s family, to seek refuge in the Netherlands, which had been recently liberated itself from Spain and which had gained a reputation for religious tolerance. Although Spinoza himself did not experience firsthand the suffering and cruelty of the Spanish Inquisition, I believe that tragic episode and the intolerance and oppression his own family experienced went a long way in producing both his deep antipathy towards religion and his controversial philosophical ideas. Rather than leading humankind toward joy and happiness, Spinoza thought religion produced only suffering and misery. Rather than being anchored in reason and rationality, Spinoza thought religion was rooted in superstition and fear. And rather than encouraging the best in human nature, Spinoza accused religion of creating an attitude of exclusivism that had led to acts of unspeakable violence and injustice, like those experienced by the Jews of Spain. I want to take a moment to explore two important aspects of Spinoza's philosophy that flow directly from his critique of religion. First, there can be little doubt that one of the most important and influential aspects of Spinoza's philosophy is his fascinating understanding of God. That understanding has attracted some of the world's great minds, including Albert Einstein, who claimed repeatedly to believe in the God of Spinoza. Rather than seeing God as many religions do - as a supernatural being moved by very human emotions like jealousy and vengeance or sympathy and compassion - Spinoza conceived of God as reality itself - as the very substance of existence. God is not distinct from or above reality; God is reality. God is everything - the air, the earth, you, me, the laws and regularities of the cosmos, and so on. Spinoza often used a Latin phrase Deus Sive Natura, meaning God and Nature, to describe ultimate reality. And this simple phrase points to his conviction that God and nature are one reality and one substance, one causal source of everything that exists. God and nature are one. And if God is everything, if God is all of reality rather than a supernatural being belonging to one faith or one sacred text, then much of what religion is based on is just plain wrong. God, in Spinoza's view, is not a Christian or a Jew, not a Hindu or a Unitarian Universalist. The divisions and conflicts waged in the name of religion are rooted in a false view of reality. God is not on anyone's side and does not choose one faith tradition or belief system over another. God does not work miracles to show his approval for one person, one group, or one belief system. In fact, there is only one side, one reality, one "fixed and immutable order of Nature," as Spinoza himself put it. Think about that for a moment. God is not particular or parochial and no single group or belief is privileged or chosen over another. I think you can begin to see why Spinoza's ideas got him into trouble with the religions of his day, including his own Judaism. And that leads us to the second key aspect of Spinoza's philosophy - his belief in the transforming power of reason. According to Spinoza, while most world religions are rooted in superstitions that appeal to our passions and fears, every human being is endowed with reason and can, therefore, come to understand themselves and God. For Spinoza, reason is the path to truth and that path is open to all. And it is the path of reason that will enable human beings to lead lives of happiness, joy, virtue, and what Spinoza called blessedness. You see, Spinoza believed that if human beings are free to learn, to seek, and to understand themselves and the world as it is rather than as they are told to believe, our understanding of ourselves and the world will broaden and become universal. We will no longer see ourselves, our faith community, or our nation as the center of the universe or as specially privileged and chosen by God above others. Instead, reason will lead us to a kind of virtuous humility in which humankind will see itself as deeply connected and part of a single, unified reality. I ask you, how much better would our world be if we followed Spinoza's path of universal freedom and reason rather than being drawn into parochial distinctions and loyalties that divide the world into us versus them and friend versus enemy? I want to leave you this morning by saying a word about the connections between Spinoza's ideas and our own Unitarian Universalism. Prior to reading that book about Spinoza, I must confess I had no idea how closely his ideas about religious truth, God, and especially about the use of reason, echo those of our own faith tradition. While I don't think its correct to say that Unitarian Universalism fully embodies Spinoza's philosophy or that Spinoza was a Unitarian Universalist and just didn't know it, there are clearly some striking similarities. And none of those similarities is more important than the close connection between Spinoza's faith in reason and Unitarian Universalism’s commitment to the free and responsible search for truth and meaning. Like Spinoza, Unitarian Universalism places its faith in the power and the possibilities of the open mind. Like Spinoza, we seek virtue and joy in this world rather than waiting for it in the next. And like Spinoza, we Unitarian Universalists find holiness in the dignity and worth of all humankind and in nature, and seek to do all that we can to understand and to live in harmony with the underlying unity of all existence. That was the "true good" Spinoza sought in his own life and for the world and that is the vision that we are called to make real this day and every day. Thanks for listening and blessed be